BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

The giant panda is a large species of bear with striking black and white patterned fur. These bears live solitary lives in dense, mountainous forests. Whilst they have been endangered in the past, their numbers are recovering.

Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of giant pandas is their striking black and white fur. Their black ears and eye patches stand out against their brilliant white, fluffy faces. They also have black limbs which contrast against their white bodies. The reason for this colouration has puzzled researchers. Some have suggested that the black and white pattern could warn other animals that the panda is dangerous (similar to skunks' black and white stripes), or that it's used for communication.1

A current leading theory is that the panda’s black and white patched body offers a ‘camouflage compromise'. In winter, at high altitude, pandas’ home forests can be snowy, in which case a white body is the best camouflage. But in the dense forests, where leopards hunt, it is better to have a patchy pattern that mimics the light and shade beneath the canopy.

The markings on pandas' faces, however, might serve another purpose. Far from making them cute, pandas’ black eyes might be used to scare predators and could help them communicate with and identify each other. Each panda’s eye patches are uniquely shaped, and they might be able to tell each other apart by them. The black patches also help their eyes to stand out – which makes it easier to see where each other is looking.

Their front paw features a "pseudothumb", which works a little bit like a human thumb and helps the bears to grip bamboo shoots. The pseudothumb is actually a wrist bone, not a finger, and is a relatively recent evolutionary adaptation which other bears do not have.2 This special adaptation exists exclusively to help pandas to eat their favourite food.

Giant pandas live solitary lives in the wild. They only encounter other pandas during the breeding season between March and May for the sole purpose of reproducing.3 Male pandas will seek out females by following their scent markings, which reveal clues about the females' readiness to mate. Males will fight other males if they come across each other.

Encouraging pandas to mate in captivity has historically been challenging, but recent efforts have been more successful as the understanding of panda mating behaviour continues to improve.4 It’s thought that male pandas are quite picky when it comes to choosing a partner, and base their decisions solely on scents. Female pandas only ovulate once a year, so the window of opportunity is small. Panda mating takes a few minutes, and pregnancy lasts up to 10 months.

In the wild, pandas can give birth every 2-3 years, but pandas in captivity are shyer about mating. This has led to a misconception that pandas are not that interested in mating. But this isn’t the case – wild pandas mate regularly.

Pandas are choosy about their dens and mate and follow scent trails over long distances, which means it is hard to recreate the perfect mating conditions for the bears in captivity. However, learnings from modern captive mating programmes have led to a greater understanding of pandas' needs, resulting in more cubs being born.

Like other bears, pandas build dens from rocks, collapsed trees or holes in tree trunks. They use these dens to raise their young, rather than to hibernate. Old growth forests contain many more suitable panda dens than secondary growth forests, with their younger, healthier trees. The loss of old growth forests to logging might be one reason that wild panda reproduction slowed in the 20th century.

Panda babies are tiny, and panda mothers usually have one at a time. The mother weighs around 900 times as much as her newborn cub – so she must be careful not to squash her offspring.

While some pandas in captivity can live well into their late 30s, wild pandas are thought to live to around 20 years on average.5 New facial recognition technology is helping researchers to accurately age wild pandas from photographs.

The giant panda once lived in habitats across the whole of China. Today, wild pandas are only found in three Chinese provinces – Sichuan, Shaanxi and Gansu.6

Because pandas largely only eat bamboo, their ranges are restricted to areas where this particular grass grows. In the past 10,000 years, as the climate has warmed, bamboo forests have become less abundant. And in recent decades, as agriculture has expanded across China, many bamboo forests have been converted into farmland.

China lost more than 30% of its forests in the second half of the 20th century due to the expansion of cities, farmland and industry. These changes have reduced the amount of habitat suitable for pandas to live in in China.

The panda’s range has moved to higher altitudes – 1,500-3,000m above sea level – as humans have encroached into their habitats. These are typically old-growth forests with ancient trees and plenty of dead tree trunks in which they can make their dens.

Giant pandas are a species of bear, which means they belong to the order Carnivora. Most bear species are largely meat-eaters who supplement their diets with berries, roots and fruit. Giant pandas are an exception to this rule. They almost exclusively eat bamboo – a type of grass.7 They might, however, occasionally eat other foods, like insects, small birds, mammals or the carcasses of other animals to help supplement their diets.

Because bamboo is not very nutritious, pandas have to eat lots of it – up to 12.5kg – and spend up to 14 hours foraging each day. Their guts are inefficient at extracting nutrients from bamboo as they are similar to those of their carnivorous relatives’ and are not evolved to process plants. This means a lot of the bamboo they eat goes straight through their digestive system – meaning pandas poo around 100 times a day.

While the panda’s gut is structurally similar to the gut of meat-eating animals, theirs contains microbes which are capable of specifically digesting bamboo.

But why eat bamboo if it’s so low on nutrition? Pandas are experts at conserving energy. Their thick fur limits the amount of energy they lose as heat, they don’t move around very much, and their organs are smaller than those of animals of a similar size. All of these adaptations mean they can survive on a low-nutrition diet.

In addition, bamboo is not a particularly popular source of food – few other animals eat it. This means that pandas are not competing for food with other species. So, while it might seem odd that pandas have to eat so much of something so hard to digest, consuming a more exclusive food does give them an advantage.

The giant panda has been the focus of intense conservation efforts since the 1980s, and as a result, their numbers are stabilising and recovering. Today, China is home to 1,860 wild pandas.8 At their lowest number, only 1,216 were recorded in the wild in the late 1980s.

China has introduced measures to protect existing forests and replant forest in areas which have been cleared in recent decades. This has resulted in an 18% increase in the amount of suitable habitat for pandas.

There is also an intensive international breeding programme which aims to breed pandas in captivity and reintroduce them to the wild.

Climate change and the loss of habitat are the two greatest threats facing pandas in the 21st century.9 In the past, the bears were also hunted for their fur, but more recently, anti-poaching measures have helped to protect them from hunters.

However, while reforestation measures are increasing the amount of habitat suitable for pandas, and the population is starting to bounce back, climate change threatens more than one-third of the pandas’ bamboo forests. Over the next 80 years, the population is projected to decline again, despite recent breeding successes and efforts to protect their habitat.

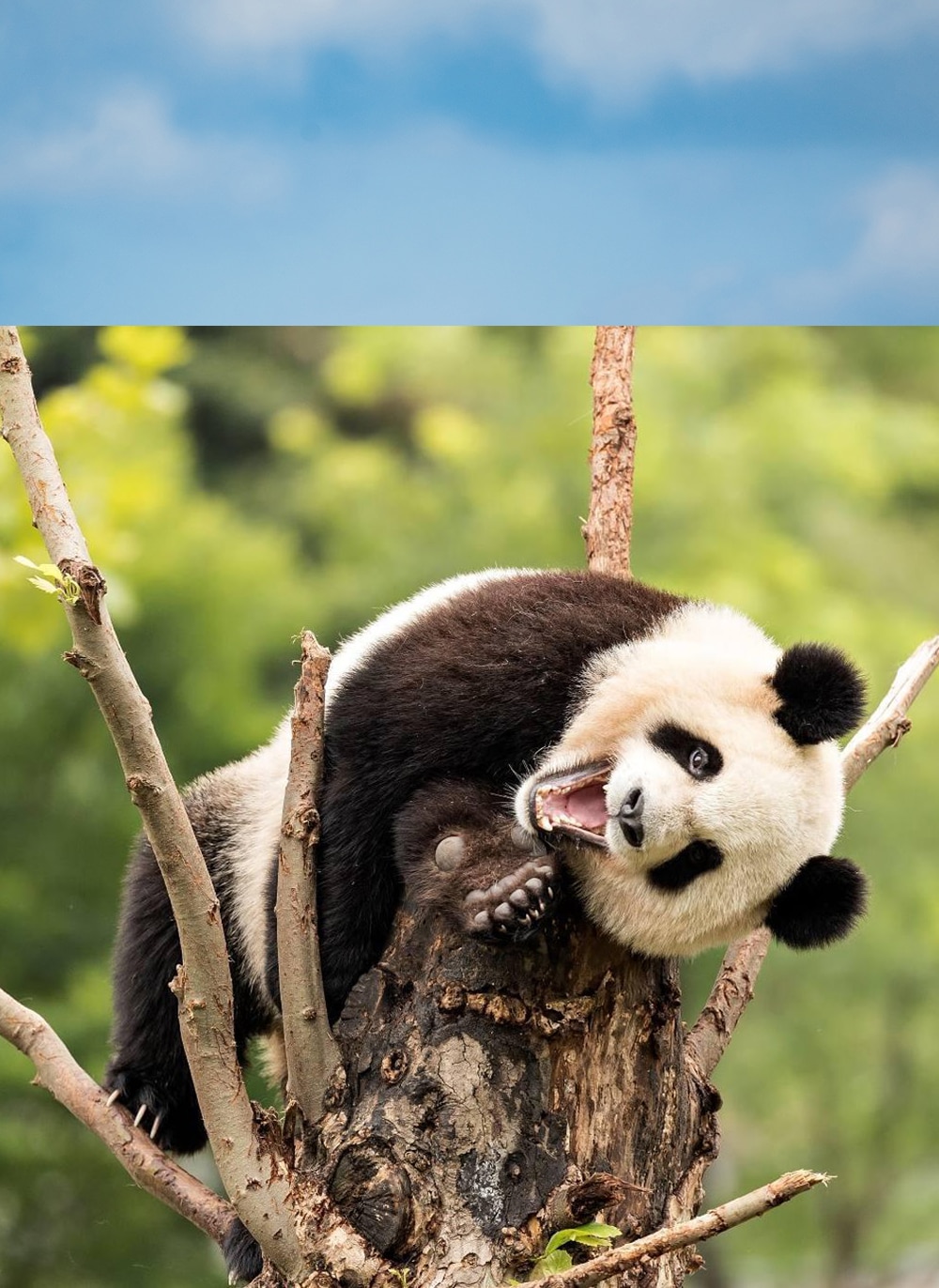

Featured image © Stella Sophie

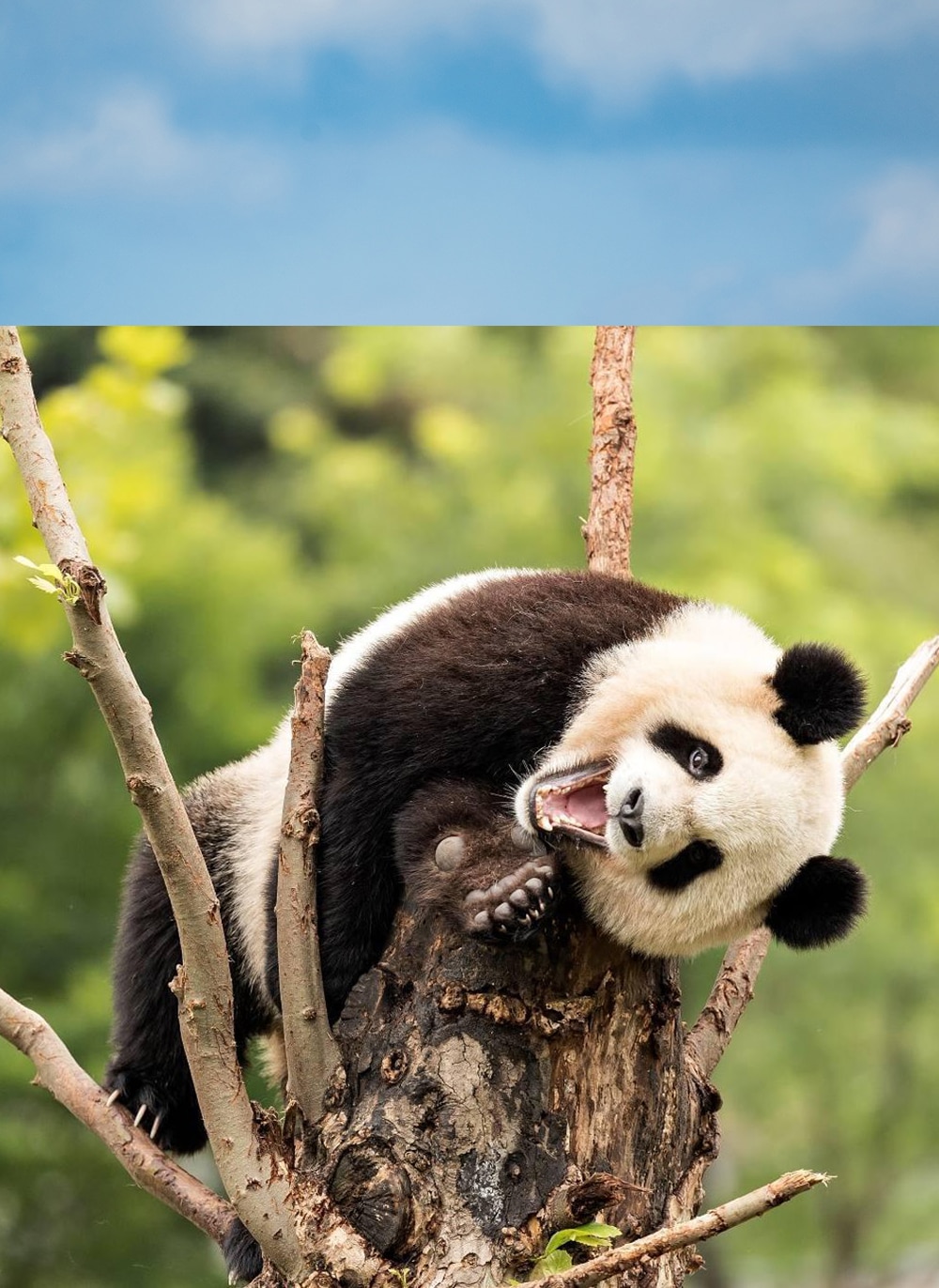

Fun fact image © Dafna Photography

1. Virginia Morell. 2017. Review of How Pandas Got Their Patches. Science.org. March 2017. https://www.science.org/content/article/how-pandas-got-their-patches.

2. “Why Do Pandas Have Thumbs? | JSTOR Daily.” 2018. JSTOR Daily. April 5, 2018. https://daily.jstor.org/why-do-pandas-have-thumbs/.

3. “Ailuropoda Melanoleuca: Swaisgood, R., Wang, D. & Wei, F.” 2016. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, April. https://doi.org/10.2305/iucn.uk.2016-2.rlts.t712a45033386.en.

4. BBC News. 2020. “Coronavirus: Pandas Mate in Lockdown at Hong Kong Zoo after Ten Years Trying,” April 7, 2020, sec. Newsbeat. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/newsbeat-52204078

5. Zang, Hang-Xing, Han Su, Yu Qi, Lin Feng, Rong Hou, Mengnan He, Peng Liu, Ping Xu, Yanglina Yu, and Peng Chen. 2022. “Ages of Giant Panda Can Be Accurately Predicted Using Facial Images and Machine Learning.” Ecological Informatics 72 (December): 101892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2022.101892.

6. “Ailuropoda Melanoleuca: Swaisgood, R., Wang, D. & Wei, F.” 2016. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, April. https://doi.org/10.2305/iucn.uk.2016-2.rlts.t712a45033386.en.

7. “Ailuropoda Melanoleuca: Swaisgood, R., Wang, D. & Wei, F.” 2016. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, April. https://doi.org/10.2305/iucn.uk.2016-2.rlts.t712a45033386.en.

8. https://www.wwf.org.uk/learn/wildlife/giant-pandas. Last reviewed 24 January 2024.

9. “Ailuropoda Melanoleuca: Swaisgood, R., Wang, D. & Wei, F.” 2016. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, April. https://doi.org/10.2305/iucn.uk.2016-2.rlts.t712a45033386.en.

The giant panda is a large species of bear with striking black and white patterned fur. These bears live solitary lives in dense, mountainous forests. Whilst they have been endangered in the past, their numbers are recovering.

Cub

Embarrassment, sleuth

The roots, stems, shoots and leaves of bamboo

Snow leopards; jackals; eagles; and martens

20 years on average in the wild

Up to 1.9m (6.2ft)

Up to 125kg

1,860 in the wild

Panda cubs are around 900 times smaller than their mothers when they are born.

Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of giant pandas is their striking black and white fur. Their black ears and eye patches stand out against their brilliant white, fluffy faces. They also have black limbs which contrast against their white bodies. The reason for this colouration has puzzled researchers. Some have suggested that the black and white pattern could warn other animals that the panda is dangerous (similar to skunks' black and white stripes), or that it's used for communication.1

A current leading theory is that the panda’s black and white patched body offers a ‘camouflage compromise'. In winter, at high altitude, pandas’ home forests can be snowy, in which case a white body is the best camouflage. But in the dense forests, where leopards hunt, it is better to have a patchy pattern that mimics the light and shade beneath the canopy.

The markings on pandas' faces, however, might serve another purpose. Far from making them cute, pandas’ black eyes might be used to scare predators and could help them communicate with and identify each other. Each panda’s eye patches are uniquely shaped, and they might be able to tell each other apart by them. The black patches also help their eyes to stand out – which makes it easier to see where each other is looking.

Their front paw features a "pseudothumb", which works a little bit like a human thumb and helps the bears to grip bamboo shoots. The pseudothumb is actually a wrist bone, not a finger, and is a relatively recent evolutionary adaptation which other bears do not have.2 This special adaptation exists exclusively to help pandas to eat their favourite food.

Giant pandas live solitary lives in the wild. They only encounter other pandas during the breeding season between March and May for the sole purpose of reproducing.3 Male pandas will seek out females by following their scent markings, which reveal clues about the females' readiness to mate. Males will fight other males if they come across each other.

Encouraging pandas to mate in captivity has historically been challenging, but recent efforts have been more successful as the understanding of panda mating behaviour continues to improve.4 It’s thought that male pandas are quite picky when it comes to choosing a partner, and base their decisions solely on scents. Female pandas only ovulate once a year, so the window of opportunity is small. Panda mating takes a few minutes, and pregnancy lasts up to 10 months.

In the wild, pandas can give birth every 2-3 years, but pandas in captivity are shyer about mating. This has led to a misconception that pandas are not that interested in mating. But this isn’t the case – wild pandas mate regularly.

Pandas are choosy about their dens and mate and follow scent trails over long distances, which means it is hard to recreate the perfect mating conditions for the bears in captivity. However, learnings from modern captive mating programmes have led to a greater understanding of pandas' needs, resulting in more cubs being born.

Like other bears, pandas build dens from rocks, collapsed trees or holes in tree trunks. They use these dens to raise their young, rather than to hibernate. Old growth forests contain many more suitable panda dens than secondary growth forests, with their younger, healthier trees. The loss of old growth forests to logging might be one reason that wild panda reproduction slowed in the 20th century.

Panda babies are tiny, and panda mothers usually have one at a time. The mother weighs around 900 times as much as her newborn cub – so she must be careful not to squash her offspring.

While some pandas in captivity can live well into their late 30s, wild pandas are thought to live to around 20 years on average.5 New facial recognition technology is helping researchers to accurately age wild pandas from photographs.

The giant panda once lived in habitats across the whole of China. Today, wild pandas are only found in three Chinese provinces – Sichuan, Shaanxi and Gansu.6

Because pandas largely only eat bamboo, their ranges are restricted to areas where this particular grass grows. In the past 10,000 years, as the climate has warmed, bamboo forests have become less abundant. And in recent decades, as agriculture has expanded across China, many bamboo forests have been converted into farmland.

China lost more than 30% of its forests in the second half of the 20th century due to the expansion of cities, farmland and industry. These changes have reduced the amount of habitat suitable for pandas to live in in China.

The panda’s range has moved to higher altitudes – 1,500-3,000m above sea level – as humans have encroached into their habitats. These are typically old-growth forests with ancient trees and plenty of dead tree trunks in which they can make their dens.

Giant pandas are a species of bear, which means they belong to the order Carnivora. Most bear species are largely meat-eaters who supplement their diets with berries, roots and fruit. Giant pandas are an exception to this rule. They almost exclusively eat bamboo – a type of grass.7 They might, however, occasionally eat other foods, like insects, small birds, mammals or the carcasses of other animals to help supplement their diets.

Because bamboo is not very nutritious, pandas have to eat lots of it – up to 12.5kg – and spend up to 14 hours foraging each day. Their guts are inefficient at extracting nutrients from bamboo as they are similar to those of their carnivorous relatives’ and are not evolved to process plants. This means a lot of the bamboo they eat goes straight through their digestive system – meaning pandas poo around 100 times a day.

While the panda’s gut is structurally similar to the gut of meat-eating animals, theirs contains microbes which are capable of specifically digesting bamboo.

But why eat bamboo if it’s so low on nutrition? Pandas are experts at conserving energy. Their thick fur limits the amount of energy they lose as heat, they don’t move around very much, and their organs are smaller than those of animals of a similar size. All of these adaptations mean they can survive on a low-nutrition diet.

In addition, bamboo is not a particularly popular source of food – few other animals eat it. This means that pandas are not competing for food with other species. So, while it might seem odd that pandas have to eat so much of something so hard to digest, consuming a more exclusive food does give them an advantage.

The giant panda has been the focus of intense conservation efforts since the 1980s, and as a result, their numbers are stabilising and recovering. Today, China is home to 1,860 wild pandas.8 At their lowest number, only 1,216 were recorded in the wild in the late 1980s.

China has introduced measures to protect existing forests and replant forest in areas which have been cleared in recent decades. This has resulted in an 18% increase in the amount of suitable habitat for pandas.

There is also an intensive international breeding programme which aims to breed pandas in captivity and reintroduce them to the wild.

Climate change and the loss of habitat are the two greatest threats facing pandas in the 21st century.9 In the past, the bears were also hunted for their fur, but more recently, anti-poaching measures have helped to protect them from hunters.

However, while reforestation measures are increasing the amount of habitat suitable for pandas, and the population is starting to bounce back, climate change threatens more than one-third of the pandas’ bamboo forests. Over the next 80 years, the population is projected to decline again, despite recent breeding successes and efforts to protect their habitat.

Featured image © Stella Sophie

Fun fact image © Dafna Photography

1. Virginia Morell. 2017. Review of How Pandas Got Their Patches. Science.org. March 2017. https://www.science.org/content/article/how-pandas-got-their-patches.

2. “Why Do Pandas Have Thumbs? | JSTOR Daily.” 2018. JSTOR Daily. April 5, 2018. https://daily.jstor.org/why-do-pandas-have-thumbs/.

3. “Ailuropoda Melanoleuca: Swaisgood, R., Wang, D. & Wei, F.” 2016. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, April. https://doi.org/10.2305/iucn.uk.2016-2.rlts.t712a45033386.en.

4. BBC News. 2020. “Coronavirus: Pandas Mate in Lockdown at Hong Kong Zoo after Ten Years Trying,” April 7, 2020, sec. Newsbeat. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/newsbeat-52204078

5. Zang, Hang-Xing, Han Su, Yu Qi, Lin Feng, Rong Hou, Mengnan He, Peng Liu, Ping Xu, Yanglina Yu, and Peng Chen. 2022. “Ages of Giant Panda Can Be Accurately Predicted Using Facial Images and Machine Learning.” Ecological Informatics 72 (December): 101892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2022.101892.

6. “Ailuropoda Melanoleuca: Swaisgood, R., Wang, D. & Wei, F.” 2016. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, April. https://doi.org/10.2305/iucn.uk.2016-2.rlts.t712a45033386.en.

7. “Ailuropoda Melanoleuca: Swaisgood, R., Wang, D. & Wei, F.” 2016. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, April. https://doi.org/10.2305/iucn.uk.2016-2.rlts.t712a45033386.en.

8. https://www.wwf.org.uk/learn/wildlife/giant-pandas. Last reviewed 24 January 2024.

9. “Ailuropoda Melanoleuca: Swaisgood, R., Wang, D. & Wei, F.” 2016. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, April. https://doi.org/10.2305/iucn.uk.2016-2.rlts.t712a45033386.en.

Cub

Embarrassment, sleuth

The roots, stems, shoots and leaves of bamboo

Snow leopards; jackals; eagles; and martens

20 years on average in the wild

Up to 1.9m (6.2ft)

Up to 125kg

1,860 in the wild

Panda cubs are around 900 times smaller than their mothers when they are born.

Sorry there is no content available for your region.