BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

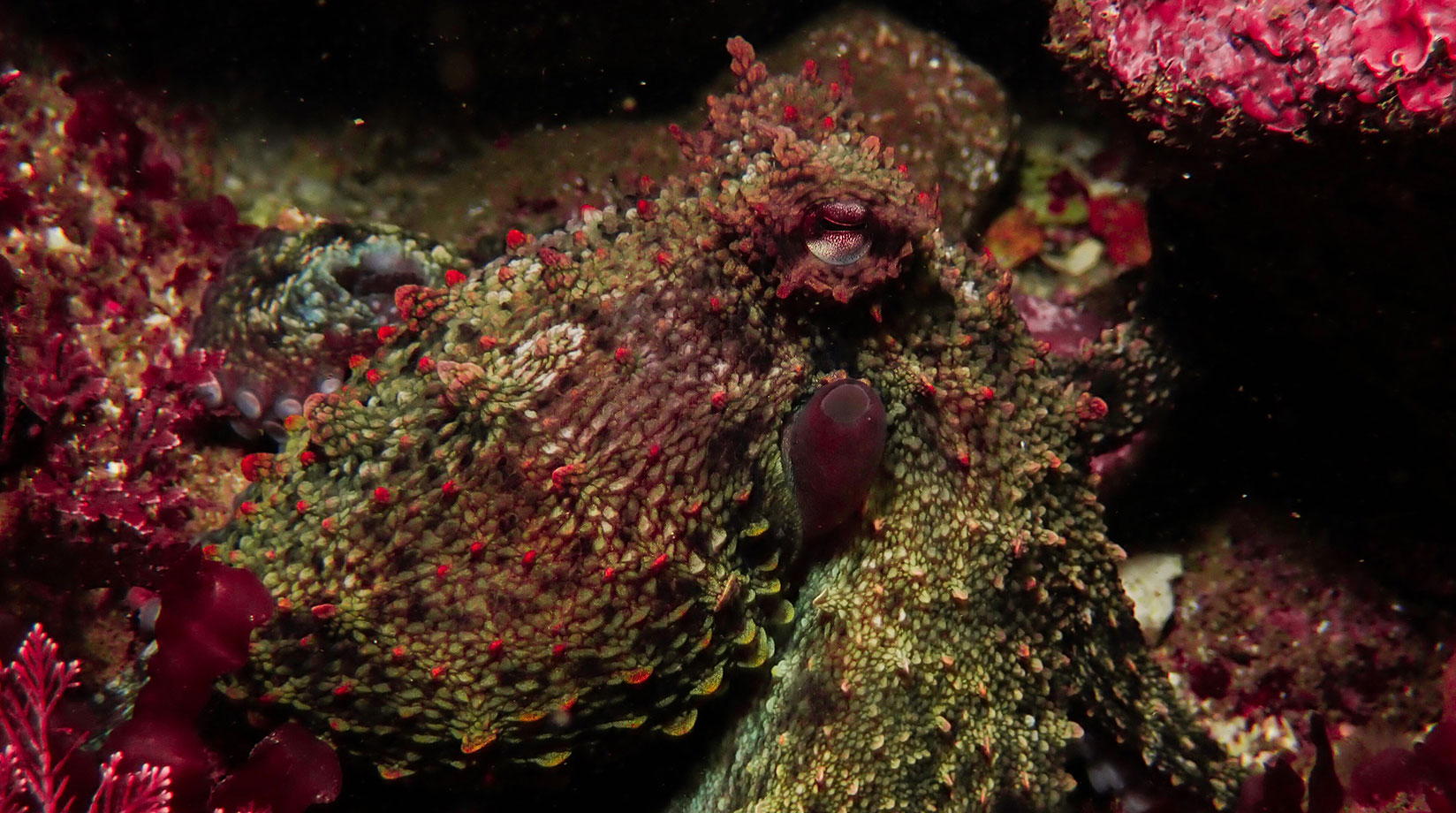

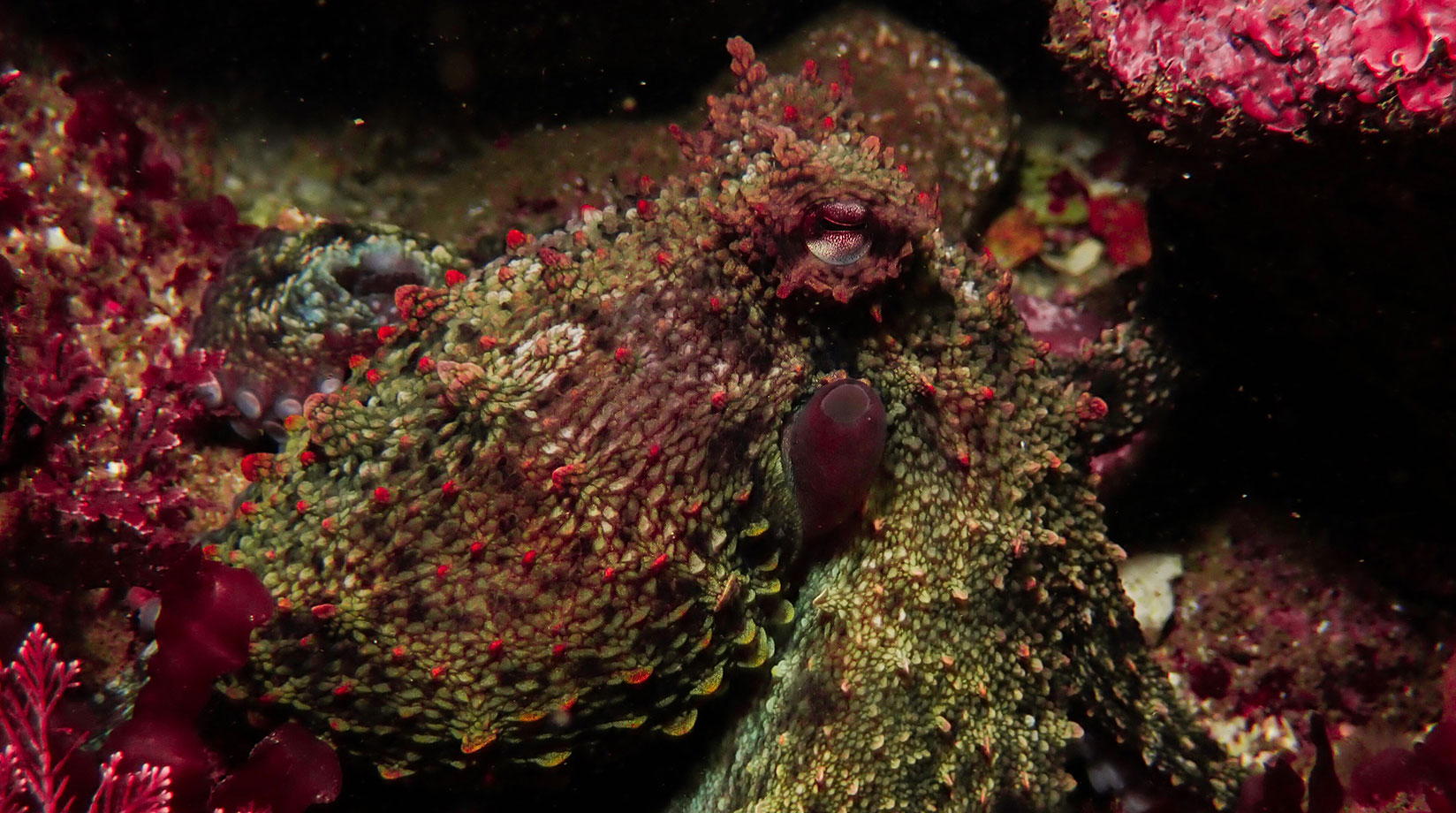

Octopuses are so unique they’ve even been branded as "alien". They are some of the smartest yet farthest removed creatures from humans, and they are masters of camouflage and great puzzle solvers.

Octopuses are among the most unique, diverse, and intelligent marine invertebrates on Earth. Inhabiting environments from shallow shores to the dark, crushing depths of the deep sea, these ancient creatures are related to some of the oldest ocean animals. Octopuses have three hearts, blue blood and a complex nervous system with one central brain and eight “mini-brains” in their arms, which can independently feel, smell, taste and even process information. Known for their remarkable camouflage abilities, octopuses are superbly adapted to crawling stealthily across the seafloor.

Octopuses are molluscs, part of a group called cephalopods, which translates from ancient Greek to "head-foot" and includes squid, cuttlefish, ammonites and nautiluses.1 Octopuses share a close relation with some of the oldest creatures in the Earth’s waters, with an evolutionary history that spans approximately 480 million years.2 Cephalopods have been abundant and diverse throughout their prehistoric existence, with over 17,000 species of fossil cephalopods identified, compared to about 800 species living today, including more than 300 species of octopuses.3

In 2022, researchers in the United States discovered the oldest direct octopus ancestor from a fossil dating back to between 325 and 328 million years ago: it had 10 arms with suckers, not the typical eight seen in modern octopuses.4

With over 300 species of octopuses populating our oceans, and new ones being discovered every year, the variety in their size is astonishing.5

The octopus Wolfi holds the record as the smallest known species and is so tiny that it can fit on a human fingertip: it is about 2.5cm in length and weighs less than 1g.6 The Atlantic pygmy octopus follows closely too, with its body typically measuring on average less than 5cm.7

At the other side of the scale, the giant Pacific octopus is one of the largest species, with females often sporting a 5-metre span from arm to arm. Some specimens have been recorded weighing as much as 70kg.

The octopus Wolfi holds the record as the smallest known species and is so tiny that it can fit on a human fingertip."

Octopuses are marine invertebrates found in every ocean but they are most abundant in temperate and warm waters worldwide.

While most octopuses dwell on the sea floor, some species float around in the vast sea without touching the ground, like the paper nautilus octopus that has evolved to make itself a shell-like structure for protection and carrying its eggs while drifting forever. But most octopuses live on surfaces at the bottom of the sea, hiding inside nooks and crannies, camouflaging with their surroundings, and making themselves dens with bits and pieces of corals and rocks. Octopuses are generally considered to be solitary creatures, spending much of their time alone.8

Most species tend to hang out along coastal areas and typically inhabit shallow waters, but several octopuses also live in the deep sea. The glass octopus lives at depths nearing 1,000m and gets its name for being see-through with bioluminescent organs.9 A rare octopus nursery was found at over 2,800m below the surface at a seamount near Costa Rica.10 The tiny dumbo octopus has been spotted plummeting almost 4,000m below the surface.11 Its squishy, soft body makes it particularly well suited to the crushing pressures of the oceanic underworld.

Octopuses do not have tentacles, they have eight muscular limbs laden with two rows of suction cups from the bottom to the top.12 The difference is that arms are also used for getting around and understanding one’s surroundings, tentacles only have suckers in clusters at the end of the appendage and they’re mainly used for hunting and eating. For instance, squids and cuttlefish, the cousins of octopuses, have eight short arms for locomotion and two longer tentacles for hooking in their prey while adrift.13

And, crucially, the super flexible arms of octopuses can each act independently – they host two-thirds of the animal’s neurons as if each arm had a "mini brain" of its own.14 They have nerve cells that enable them to taste and smell anything they touch and proteins that sense light, so each tentacle can probe for snacks in obscure crevices at the same time.15 The arms seem to have minds of their own for about an hour even when severed off, and if they’ve been cut off they can regrow with ease like starfish limbs and lizard tails.16

Octopuses are colourful creatures that use their hues for communication, to hide from predators, or to intimidate them. These cephalopods are masters of camouflage, often hiding in plain sight by blending in with their vibrant surroundings.17

They can switch colours in the blink of an eye thanks to hundreds of thousands of specialised, pigment-containing skin cells called chromatophores, which are each individually controlled by the nervous system.18 Additionally, their skin papillae can expand or contract to change their texture from smooth to spiky, matching the rocks or corals around them.19

The southern keeled octopus hides in the sand making itself all the iridescent shades of pale white, grey, and beige of the bottom of the ocean.20 The algae octopus conceals itself by looking like a shell covered in fuzzy algae.21 The mimic octopus brings this skill to another level, disguising itself as the animals that its predators would want to stay away from. Using its coloured patterns, shape, and movement, it can turn itself into a lookalike of a poisonous flatfish, jellyfish, lionfish, crab, or deadly black and white sea snake.22

Octopus camouflage techniques are so intriguing that scientists are trying to develop synthetic skins that can pull off the same feats.23

Octopuses spend their time stretching and scrunching around because they lack a skeleton – they’re invertebrates! – and they are made up of almost 90% muscle.24 Thanks to their soft, mushy bodies they can fold, bend and tuck into super tiny crevices and holes, squeezing into any space larger than their beak, which is the only hard part of their body.

To travel in the open water, octopuses use jet propulsion: they suck water into a part of their body called a siphon and then they shoot it out for a push.25 To move around on the sea floor, the eight-armed cephalopods tend to use all of their limbs to crawl and grab onto nooks and pick on crannies.26 Funnily enough, in moments of danger, some octopuses have been seen swiftly running away on just two arms without breaking camouflage, not letting their predator spot they are eight-armed octopuses.27

An octopus’s mouth is found right under its head, at the centre of its eight-armed skirt: it's a hard, scissor-like beak made of the same material as crab shells. Having a firm bill comes in handy for crushing and crunching through the shells of its preferred prey – crabs, lobsters, shrimp and smalller molluscs like whelks, clams, and mussels.28

Octopuses are carnivorous and mainly eat other sea creatures.29 They excel at nocturnal hunting and are also opportunistic hunters: they will gnaw away at whatever they can find in their habitat, tweaking their diet according to what’s available.30

Octopuses have three hearts – two hearts focus on moving blood to the cephalopod’s gills so it can get oxygenated and then one "systemic" heart which circulates that blood to the rest of their organs in a super-efficient system.31 Interestingly, the systemic heart pauses when an octopus swims, which is probably why octopuses prefer to crawl than swim.32

In addition to having three hearts, octopuses also possess blue blood.33 Instead of using iron-based haemoglobin to transport oxygen in their blood (like we humans do), octopuses use copper-based haemocyanin. This adaptation not only gives their blood its distinctive blue colour but also helps them survive in deep, cold waters.34 But when exposed to air, their blood loses oxygen and turns clear.35

Octopuses have a main central brain able to exert top-down control on all other brains, and then eight “mini brains” because each arm has its independent network of neurons grouped in nodules called ganglia.36

The central brain is doughnut-shaped because it rings around the animal’s oesophagus, a tube that traverses its entire body. Relative to the size of their bodies, octopuses have the largest brains of any invertebrate: they have around 500 million neurons, as much as a dog.37

Octopuses are some of the smartest animals known to science.38

They can open jars from the inside and the outside. They can tell shapes apart and fit L-shaped puzzle pieces into matching holes.39 They can use tools to protect themselves – coconut octopuses use sunken coconut shells to hide – and to hunt.40 They have good both short and long-term memory.41 They can recognise objects on screens.42 They can recognise people, and prefer some to others.43 They can learn from observing other octopuses.44

It turns out octopuses might even dream. In 2021, scientists recording an octopus through its slumber found that every half hour, the creature experienced skin colour changes for one to two minutes – just like humans blink their eyes during REM sleep.45 In 2023, similar research caught an octopus tossing and turning during its deep sleep, as if experiencing nightmares.46 This is a quirk that might help scientists show octopuses are more similar to highly developed animals than previously thought, but some researchers think it might be too soon to make these parallels.47

Given their highly adaptable cognitive abilities, scholars have long upheld octopuses are conscious and sentient. 48

Male octopuses don’t have penises; instead, they have a specialised arm called a hectocotylus, used to transfer sperm directly into a female’s mantle cavity.49 These modified arms vary in appearance – resembling syringes, spoons or even toast racks.50 Argonauts – the octopuses that float around water in their paper-like shell constructions – don’t always just deliver the sperm packet inside the female, they often leave their whole hectocotylus with her.51

This adaptation is particularly useful for protection, as many female octopuses are known to often consume their mates after copulating: biting, strangling and then eating them.52 Using an extended arm to deliver sperm comes in handy for the sake of protection, since most female octopuses like to take a big hard bite at their mate after the act, strangling and eating them.53 However, not all species follow this gruesome pattern. The larger Pacific striped octopus mates face-to-face in a gentle, less cannibalistic way, suggesting a more nuanced approach to octopus mating than previously thought.

After mating, the lifecycle of octopuses concludes rapidly. Males often die shortly after delivering their sperm: they wander off alone and die in the next weeks (sometimes months). Females, once fertilised, lay thousands of eggs, and dedicate the rest of their life to guarding them obsessively – to the point of their death. While safe-keeping their clutch, mother octopuses stop eating, and their body starts deteriorating from the inside, a death spiral slowly killing them.54 This mechanism is triggered by something inside the animal’s optic glands.55

In many plants and animals, this strategy of dying after mating once is called semelparity. Evolutionary biologists think it maximises a species' ability to pass on its genes. By channelling all of their energy into a single reproductive moment, these animals increase the likelihood of producing one batch of numerous, healthy offspring. The opposite of semelparity is iteroparity, and it's when animals reproduce several times during their lifetime.

One octopus mother in California made headlines for brooding her clutch of eggs for more than four and a half years before the eggs had hatched, giving life to miniature adults ready to forage in plankton until old enough to eat bigger fish.56

Just like squids, most octopuses can squirt ink. When threatened by predators and trying to get away, octopuses can squirt black ink in their faces: the dark liquid is made of a chemical called tyrosinase, which clouds the predator’s vision, disorients them and disrupts their sense of taste and smell.57 The ink is such an irritant that it can end up killing the octopus itself if it doesn’t get away quickly enough.58

Yes, all octopuses are venomous: they can inject toxins into a prey or predator with a small bite from their hard beaks. Although most octopus venom isn’t dangerous to humans, it can be lethal to smaller prey.59

The most venomous octopus species is the blue-ringed octopus – and this does pose a threat to humans.60 This small cephalopod – some species measuring just up to 6cm in size – injects a neurotoxin far more powerful than cyanide, capable of causing a human’s death in a matter of minutes.61 It’s not aggressive, though, and only attacks if provoked. This octopus's deadliness is signalled by vibrant blue rings on its mantle: they’re a warning sign to stay away.

Octopuses were traditionally thought to be solitary creatures, each fending for themselves. But a growing body of research is starting to suggest otherwise.

In Australia, marine biologists discovered up to 30 gloomy octopuses that have built underwater cities – dubbed Octopolis and Octlantis – made of piles of rocks and shells where they gather in groups and share dens.62 Off the coast of California and the coast of Costa Rica, deep-sea expeditions have revealed rare brooding nurseries with several octopuses all clumped together, close to hydrothermal vents.63 The larger Pacific striped octopus, also known as LPSO, is also a particularly social species and can be found living in groups of up to 40 individuals.64 They are also the species that mates beak to beak, and their females do not die after laying their eggs, unlike most.

When scientists gave two California two-spot octopuses MDMA – a drug that induces feelings of euphoria and sociability – the typically asocial species became warm and curious towards each other.65 This behaviour suggests that octopuses might have brain systems similar to humans for social interactions.66

Featured image © Greens and Blues | Shutterstock

Fun fact image © Masaaki Komori | Unsplash

1. “Cephalopods.” 2023. Montereybayaquarium.org. 2023. https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/cephalopods.

2. “Chambered Nautilus.” Montereybayaquarium.org, 2020, www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/chambered-nautilus.

3. Vendetti, Jann. “The Cephalopoda.” Berkeley.edu, 2006, ucmp.berkeley.edu/taxa/inverts/mollusca/cephalopoda.php.

4. Whalen, Christopher D., and Neil H. Landman. “Fossil Coleoid Cephalopod from the Mississippian Bear Gulch Lagerstätte Sheds Light on Early Vampyropod Evolution.” Nature Communications, vol. 13, no. 1, 8 Mar. 2022, www.nature.com/articles/s41467-022-28333-5.pdf, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28333-5.

5. Mock-Bunting, Logan. “Scientists Discover Four New Species of Deep-Sea Octopus.” Schmidt Ocean Institute, 16 Jan. 2024, schmidtocean.org/scientists-discover-four-new-species-of-deep-sea-octopus/.

6. “WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Octopus Wolfi (Wülker, 1913).” Marinespecies.org, 2024, www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=342047. Accessed 24 Sept. 2024.

7. Rudolph, Nichole. “Octopus Joubini.” Animal Diversity Web, 2002, animaldiversity.org/accounts/Octopus_joubini/.

8. Quaglia, Sofia. “It Looks like a Shell, but an Octopus and 40,000 Eggs Live Inside.” The New York Times, 5 Nov. 2022, www.nytimes.com/2022/11/05/science/octopus-shell-argonaut.html.

9. “The Glass Octopus Is See-through and Spectacular.” Ocean Conservancy, 15 July 2021, oceanconservancy.org/blog/2021/07/15/glass-octopus/.

10. ---. “Scientists Discover New Deep-Sea Octopus Nursery in Costa Rica.” Schmidt Ocean Institute, 28 June 2023, schmidtocean.org/scientists-discover-new-deep-sea-octopus-nurseries-in-costa-rica/.

11. Oceana. “Dumbo Octopus.” Oceana, oceana.org/marine-life/dumbo-octopus/.

12. Kier, William M. “The Musculature of Coleoid Cephalopod Arms and Tentacles.” Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, vol. 4, 18 Feb. 2016, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2016.00010.

13. “Arms vs. Tentacles | Science and the Sea.” Scienceandthesea.org, 2023, www.scienceandthesea.org/program/arms-vs-tentacles#:~:text=An%20arm%20i….

14. Kennedy, E. B. Lane, et al. “Octopus Arms Exhibit Exceptional Flexibility.” Scientific Reports, vol. 10, no. 1, 30 Nov. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77873-7.

15. van Giesen, Lena, et al. “Molecular Basis of Chemotactile Sensation in Octopus.” Cell, vol. 183, no. 3, Oct. 2020, pp. 594-604.e14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.008;

Barbara, University of California-Santa. “Study Demonstrates That Octopus’s Skin Possesses Same Cellular Mechanism for Detecting Light as Its Eyes Do.” Phys.org, phys.org/news/2015-05-octopus-skin-cellular-mechanism-eyes.html;

16. Nuwer, Rachel. “Severed Octopus Arms Have a Mind of Their Own.” Smithsonian Magazine, www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/severed-octopus-arms-have-a-mind-of-t…;

Fossati, Sara Maria, et al. “Octopus Arm Regeneration: Role of Acetylcholinesterase during Morphological Modification.” Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, vol. 447, 1 Sept. 2013, pp. 93–99, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022098113000671?casa_token=…, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2013.02.015.

17. Nahmad-Rohen, Luis, et al. “The Colours of Octopus: Using Spectral Data to Measure Octopus Camouflage.” Vision, vol. 6, no. 4, 22 Sept. 2022, p. 59, https://doi.org/10.3390/vision6040059.

18. Fox Meyer. 2019. “How Octopuses and Squids Change Color.” Si.edu. March 29, 2019. https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/invertebrates/how-octopuses-and-squids-….

19. Nahmad-Rohen, Luis, et al. “The Colours of Octopus: Using Spectral Data to Measure Octopus Camouflage.” Vision, vol. 6, no. 4, 22 Sept. 2022, p. 59, https://doi.org/10.3390/vision6040059.

20. News, Opening Hours Mon-Wed: 9am-9pm Thurs-Sun: 9am-5pm during February 2024 Address 1 William StreetSydney NSW 2010 Australia Phone +61 2 9320 6000 www australian museum Copyright © 2024 The Australian Museum ABN 85 407 224 698 View Museum. n.d. “Southern Keeled Octopus.” The Australian Museum. https://australian.museum/learn/animals/molluscs/southern-keeled-octopu….

21. Marinebio. 2017. “Mimic Octopuses ~ MarineBio Conservation Society.” Marine Bio. 2017. https://www.marinebio.org/species/mimic-octopuses/thaumoctopus-mimicus/.

22. Getty Images TV. 2017. “Mimic Octopus: Master of Disguise.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wos8kouz810.

23. 2017b. “Stretchable Surfaces with Programmable 3D Texture Morphing for Synthetic Camouflaging Skins.” Science 358 (6360): 210–14. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan5627.

24. “Octopus | National Wildlife Federation.” 2024b. National Wildlife Federation. 2024. https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Invertebrates/….

25. Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. n.d. “Octopus Movement.” Teara.govt.nz. https://teara.govt.nz/en/video/7906/octopus-movement#:~:text=Octopus%20….

26. 2015b. “Octopus Movement: Push Right, Go Left.” Current Biology 25 (9): R366–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.066.

27. 2009c. “Defensive Tool Use in a Coconut-Carrying Octopus.” Current Biology 19 (23): R1069–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.052.

28. Altman, J. S., and M. Nixon. 2009. “Use of the Beaks and Raduala by Octopus Vulgaris in Feeding.” Journal of Zoology 161 (1): 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1970.tb02167.x;

29. 2015b. “Octopus Movement: Push Right, Go Left.” Current Biology 25 (9): R366–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.066.

30. “What Does an Octopus Eat?” 2023. American Oceans. June 16, 2023. https://www.americanoceans.org/facts/what-do-octopus-eat/#:~:text=Octop….

31. “Circulatory System.” 2009. Brown.edu. May 11, 2009. https://charlotte.neuro.brown.edu/~sheinb/octopus/documents/43.html;

Wells, M. J., and P. J. S. Smith. 1987. “The Performance of the Octopus Circulatory System: A Triumph of Engineering over Design.” Experientia 43 (5): 487–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02143577.

32. When you give an octopus a go prohttps://www.sheddaquarium.org/stories/eight-strange-and-wonderful-facts….

33. Schwarcz, Joe. 2018. “Snails, Spiders, and Octopi All Have Blue Blood.” Office for Science and Society. February 15, 2018. https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/did-you-know/snails-spiders-and-octup….

34. “Blue Blood on Ice – How an Antarctic Octopus Survives the Cold.” n.d. Www.biomedcentral.com. https://www.biomedcentral.com/about/press-centre/science-press-releases….

35. 2018. Nhm.ac.uk. 2018. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/octopuses-keep-surprising-us-here-are-ei….

36. Natural History Museum. 2018. “How Brainy Is an Octopus? | Natural History Museum.” YouTube. October 8, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2x1dxoNA3k0&list=TLGGIDDeugoxOnkyNzAyMj….

37. Hochner, Binyamin. 2012. “An Embodied View of Octopus Neurobiology.” Current Biology 22 (20): R887–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.001;

Hendry, Lisa. n.d. “Octopuses Keep Surprising Us - Here Are Eight Examples How.” Www.nhm.ac.uk. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/octopuses-keep-surprising-us-here-are-ei….

38. Godfrey-Smith, Peter. 2016. “The Mind of an Octopus.” Scientific American Mind 28 (1): 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamericanmind0117-62.

39. Sutherland, N. S. 1960. “The Visual Discrimination of Shape by Octopus: Squares and Rectangles.” Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 53 (1): 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0038429;

Richter, Jonas N., Binyamin Hochner, and Michael J. Kuba. 2016. “Pull or Push? Octopuses Solve a Puzzle Problem.” Edited by Daniel Osorio. PLOS ONE 11 (3): e0152048. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152048.

40. “BBC News - Octopus Snatches Coconut and Runs.” 2024. Bbc.co.uk. BBC. 2024. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/8408233.stm.

41. Zarrella, Ilaria, Giovanna Ponte, Elena Baldascino, and Graziano Fiorito. 2015. “Learning and Memory in Octopus Vulgaris: A Case of Biological Plasticity.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 35 (December): 74–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2015.06.012.

42. Kawashima, Sumire, Kaishu Takei, Saki Yoshikawa, Haruhiko Yasumuro, and Yuzuru Ikeda. 2020. “Tropical Octopus Abdopus Aculeatus Can Learn to Recognize Real and Virtual Symbolic Objects.” The Biological Bulletin 238 (1): 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1086/707420.

43. Anderson, Roland C., Jennifer A. Mather, Mathieu Q. Monette, and Stephanie R. M. Zimsen. 2010. “Octopuses (Enteroctopus Dofleini) Recognize Individual Humans.” Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 13 (3): 261–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2010.483892.

44. Fiorito, G., and P. Scotto. 1992. “Observational Learning in Octopus Vulgaris.” Science 256 (5056): 545–47. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.256.5056.545.

45. Medeiros, Sylvia Lima de Souza, Mizziara Marlen Matias de Paiva, Paulo Henrique Lopes, Wilfredo Blanco, Françoise Dantas de Lima, Jaime Bruno Cirne de Oliveira, Inácio Gomes Medeiros, et al. 2021. “Cyclic Alternation of Quiet and Active Sleep States in the Octopus.” IScience 0 (0). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102223.

46. Eric Angel Ramos, Mariam Steinblatt, Rachel Demsey, Diana Reiss, and Marcelo O Magnasco. 2023. “Abnormal Behavioral Episodes Associated with Sleep and Quiescence in Octopus Insularis: Possible Nightmares in a Cephalopod?,” May. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.11.540348.

47. Pophale, Aditi, Kazumichi Shimizu, Tomoyuki Mano, Teresa L. Iglesias, Kerry Martin, Makoto Hiroi, Keishu Asada, et al. 2023. “Wake-like Skin Patterning and Neural Activity during Octopus Sleep.” Nature 619 (7968): 129–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06203-4;

Bugos, Claire. n.d. “Heidi the Snoozing Octopus May Not Be Dreaming after All.” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/heidi-snoozing-octopus-may-no….

48. Mather, Jennifer. 2021. “Octopus Consciousness: The Role of Perceptual Richness.” NeuroSci 2 (3): 276–90. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci2030020.

49. “Hectocotylus | Mollusk Anatomy | Britannica.” n.d. Www.britannica.com. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/science/hectocotylus.

50. Hendry, Lisa. 2018. “Octopuses Keep Surprising Us - Here Are Eight Examples How.” Nhm.ac.uk. 2018. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/octopuses-keep-surprising-us-here-are-ei….

51. Battaglia, P., M. G. Stipa, G. Ammendolia, C. Pedà, P. Consoli, F. Andaloro, and T. Romeo. 2021. “When Nature Continues to Surprise: Observations of the Hectocotylus of Argonauta Argo, Linnaeus 1758.” The European Zoological Journal 88 (1): 980–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750263.2021.1970260.

52. Huffard, Christine L., and Mike Bartick. 2014. “WildWunderpus PhotogenicusandOctopus Cyaneaemploy Asphyxiating ‘Constricting’ in Interactions with Other Octopuses.” Molluscan Research 35 (1): 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13235818.2014.909558.

53. “6 Animals That Eat Their Mates | Britannica.” n.d. Www.britannica.com. Accessed April 25, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/list/6-animals-that-eat-their-mates#:~:text=…;

2014b. “WildWunderpus PhotogenicusandOctopus Cyaneaemploy Asphyxiating ‘Constricting’ in Interactions with Other Octopuses.” Molluscan Research 35 (1): 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13235818.2014.909558.

54. Wood, Matt. 2015. “ the Grim, Final Days of a Mother Octopus.” Uchicagomedicine.org. UChicago Medicine. 2015. https://www.uchicagomedicine.org/forefront/biological-sciences-articles….

55. Wang, Z. Yan, Melissa R. Pergande, Clifton W. Ragsdale, and Stephanie M. Cologna. 2022. “Steroid Hormones of the Octopus Self-Destruct System.” Current Biology 32 (11): 2572-2579.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.04.043.

56. Imbler, Sabrina. 2022. “The ‘Mother of the Year’ Who Starved for 53 Months.” The Atlantic. December 5, 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2022/12/pacific-octopus-vig….

57. Derby, Charles. 2014. “Cephalopod Ink: Production, Chemistry, Functions and Applications.” Marine Drugs 12 (5): 2700–2730. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12052700.

58. Frey, Michelle. 2022. “Why Do Cephalopods Use Ink?” Ocean Conservancy. June 23, 2022. https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2022/06/23/cephalopods-ink/.

59. News, NBC. 2009. “All Octopuses Are Venomous.” NBC News. NBC News. April 16, 2009. https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna30248367.

60. Osterloff, Emily. n.d. “The Blue-Ringed Octopus: Small, Vibrant and Deadly.” Www.nhm.ac.uk. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/blue-ringed-octopus-small-vibrant-deadly….

61. “Blue Ringed Octopus | AIMS.” n.d. Www.aims.gov.au. https://www.aims.gov.au/docs/projectnet/blue-ringed-octopus.html#:~:tex…;

Spencer, Erin. 2018. “The Blue-Ringed Octopus: Small but Deadly - Ocean Conservancy.” Ocean Conservancy. September 13, 2018. https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2017/03/13/the-blue-ringed-octopus-sm….

62 . Skokstad, Erik, “Scientists discover and underwater city full of gloomy octopuses”https://www.science.org/content/article/scientists-discover-underwater-…

63. 2023b. “Scientists Discover New Deep-Sea Octopus Nursery in Costa Rica.” Schmidt Ocean Institute. June 28, 2023. https://schmidtocean.org/scientists-discover-new-deep-sea-octopus-nurse….

64. #author.fullName}. n.d. “Octopuses Were Thought to Be Solitary until a Social Species Turned Up.” New Scientist. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg24432610-400-octopuses-were-thou….

65. Nuwer, Rachel. 2018. “Rolling under the Sea: Scientists Gave Octopuses Ecstasy to Study Social Behavior.” Scientific American, December. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican1218-18.

66. Edsinger, Eric, and Gül Dölen. 2018. “A Conserved Role for Serotonergic Neurotransmission in Mediating Social Behavior in Octopus.” Current Biology 28 (19): 3136-3142.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.061.

Octopuses are so unique they’ve even been branded as "alien". They are some of the smartest yet farthest removed creatures from humans, and they are masters of camouflage and great puzzle solvers.

Fry

Consortium

Mainly fish, marine invertebrates, crustaceans and shellfish

Mainly humans, fish, seals, whales, birds, and sea otters

Common octopus 1-2 years, some other species up to 5 years

Varies greatly depending on species, as small as 2cm to as large as stretching to 5m from arm to arm

Varies greatly depending on species, as light as less than a gram to as hefty 20-50kg, with the heaviest recorded individual weighing 70kg

Octopuses have eight arms – not tentacles. And each arm is capable of acting autonomously.

Octopuses are among the most unique, diverse, and intelligent marine invertebrates on Earth. Inhabiting environments from shallow shores to the dark, crushing depths of the deep sea, these ancient creatures are related to some of the oldest ocean animals. Octopuses have three hearts, blue blood and a complex nervous system with one central brain and eight “mini-brains” in their arms, which can independently feel, smell, taste and even process information. Known for their remarkable camouflage abilities, octopuses are superbly adapted to crawling stealthily across the seafloor.

Octopuses are molluscs, part of a group called cephalopods, which translates from ancient Greek to "head-foot" and includes squid, cuttlefish, ammonites and nautiluses.1 Octopuses share a close relation with some of the oldest creatures in the Earth’s waters, with an evolutionary history that spans approximately 480 million years.2 Cephalopods have been abundant and diverse throughout their prehistoric existence, with over 17,000 species of fossil cephalopods identified, compared to about 800 species living today, including more than 300 species of octopuses.3

In 2022, researchers in the United States discovered the oldest direct octopus ancestor from a fossil dating back to between 325 and 328 million years ago: it had 10 arms with suckers, not the typical eight seen in modern octopuses.4

With over 300 species of octopuses populating our oceans, and new ones being discovered every year, the variety in their size is astonishing.5

The octopus Wolfi holds the record as the smallest known species and is so tiny that it can fit on a human fingertip: it is about 2.5cm in length and weighs less than 1g.6 The Atlantic pygmy octopus follows closely too, with its body typically measuring on average less than 5cm.7

At the other side of the scale, the giant Pacific octopus is one of the largest species, with females often sporting a 5-metre span from arm to arm. Some specimens have been recorded weighing as much as 70kg.

The octopus Wolfi holds the record as the smallest known species and is so tiny that it can fit on a human fingertip."

Octopuses are marine invertebrates found in every ocean but they are most abundant in temperate and warm waters worldwide.

While most octopuses dwell on the sea floor, some species float around in the vast sea without touching the ground, like the paper nautilus octopus that has evolved to make itself a shell-like structure for protection and carrying its eggs while drifting forever. But most octopuses live on surfaces at the bottom of the sea, hiding inside nooks and crannies, camouflaging with their surroundings, and making themselves dens with bits and pieces of corals and rocks. Octopuses are generally considered to be solitary creatures, spending much of their time alone.8

Most species tend to hang out along coastal areas and typically inhabit shallow waters, but several octopuses also live in the deep sea. The glass octopus lives at depths nearing 1,000m and gets its name for being see-through with bioluminescent organs.9 A rare octopus nursery was found at over 2,800m below the surface at a seamount near Costa Rica.10 The tiny dumbo octopus has been spotted plummeting almost 4,000m below the surface.11 Its squishy, soft body makes it particularly well suited to the crushing pressures of the oceanic underworld.

Octopuses do not have tentacles, they have eight muscular limbs laden with two rows of suction cups from the bottom to the top.12 The difference is that arms are also used for getting around and understanding one’s surroundings, tentacles only have suckers in clusters at the end of the appendage and they’re mainly used for hunting and eating. For instance, squids and cuttlefish, the cousins of octopuses, have eight short arms for locomotion and two longer tentacles for hooking in their prey while adrift.13

And, crucially, the super flexible arms of octopuses can each act independently – they host two-thirds of the animal’s neurons as if each arm had a "mini brain" of its own.14 They have nerve cells that enable them to taste and smell anything they touch and proteins that sense light, so each tentacle can probe for snacks in obscure crevices at the same time.15 The arms seem to have minds of their own for about an hour even when severed off, and if they’ve been cut off they can regrow with ease like starfish limbs and lizard tails.16

Octopuses are colourful creatures that use their hues for communication, to hide from predators, or to intimidate them. These cephalopods are masters of camouflage, often hiding in plain sight by blending in with their vibrant surroundings.17

They can switch colours in the blink of an eye thanks to hundreds of thousands of specialised, pigment-containing skin cells called chromatophores, which are each individually controlled by the nervous system.18 Additionally, their skin papillae can expand or contract to change their texture from smooth to spiky, matching the rocks or corals around them.19

The southern keeled octopus hides in the sand making itself all the iridescent shades of pale white, grey, and beige of the bottom of the ocean.20 The algae octopus conceals itself by looking like a shell covered in fuzzy algae.21 The mimic octopus brings this skill to another level, disguising itself as the animals that its predators would want to stay away from. Using its coloured patterns, shape, and movement, it can turn itself into a lookalike of a poisonous flatfish, jellyfish, lionfish, crab, or deadly black and white sea snake.22

Octopus camouflage techniques are so intriguing that scientists are trying to develop synthetic skins that can pull off the same feats.23

Octopuses spend their time stretching and scrunching around because they lack a skeleton – they’re invertebrates! – and they are made up of almost 90% muscle.24 Thanks to their soft, mushy bodies they can fold, bend and tuck into super tiny crevices and holes, squeezing into any space larger than their beak, which is the only hard part of their body.

To travel in the open water, octopuses use jet propulsion: they suck water into a part of their body called a siphon and then they shoot it out for a push.25 To move around on the sea floor, the eight-armed cephalopods tend to use all of their limbs to crawl and grab onto nooks and pick on crannies.26 Funnily enough, in moments of danger, some octopuses have been seen swiftly running away on just two arms without breaking camouflage, not letting their predator spot they are eight-armed octopuses.27

An octopus’s mouth is found right under its head, at the centre of its eight-armed skirt: it's a hard, scissor-like beak made of the same material as crab shells. Having a firm bill comes in handy for crushing and crunching through the shells of its preferred prey – crabs, lobsters, shrimp and smalller molluscs like whelks, clams, and mussels.28

Octopuses are carnivorous and mainly eat other sea creatures.29 They excel at nocturnal hunting and are also opportunistic hunters: they will gnaw away at whatever they can find in their habitat, tweaking their diet according to what’s available.30

Octopuses have three hearts – two hearts focus on moving blood to the cephalopod’s gills so it can get oxygenated and then one "systemic" heart which circulates that blood to the rest of their organs in a super-efficient system.31 Interestingly, the systemic heart pauses when an octopus swims, which is probably why octopuses prefer to crawl than swim.32

In addition to having three hearts, octopuses also possess blue blood.33 Instead of using iron-based haemoglobin to transport oxygen in their blood (like we humans do), octopuses use copper-based haemocyanin. This adaptation not only gives their blood its distinctive blue colour but also helps them survive in deep, cold waters.34 But when exposed to air, their blood loses oxygen and turns clear.35

Octopuses have a main central brain able to exert top-down control on all other brains, and then eight “mini brains” because each arm has its independent network of neurons grouped in nodules called ganglia.36

The central brain is doughnut-shaped because it rings around the animal’s oesophagus, a tube that traverses its entire body. Relative to the size of their bodies, octopuses have the largest brains of any invertebrate: they have around 500 million neurons, as much as a dog.37

Octopuses are some of the smartest animals known to science.38

They can open jars from the inside and the outside. They can tell shapes apart and fit L-shaped puzzle pieces into matching holes.39 They can use tools to protect themselves – coconut octopuses use sunken coconut shells to hide – and to hunt.40 They have good both short and long-term memory.41 They can recognise objects on screens.42 They can recognise people, and prefer some to others.43 They can learn from observing other octopuses.44

It turns out octopuses might even dream. In 2021, scientists recording an octopus through its slumber found that every half hour, the creature experienced skin colour changes for one to two minutes – just like humans blink their eyes during REM sleep.45 In 2023, similar research caught an octopus tossing and turning during its deep sleep, as if experiencing nightmares.46 This is a quirk that might help scientists show octopuses are more similar to highly developed animals than previously thought, but some researchers think it might be too soon to make these parallels.47

Given their highly adaptable cognitive abilities, scholars have long upheld octopuses are conscious and sentient. 48

Male octopuses don’t have penises; instead, they have a specialised arm called a hectocotylus, used to transfer sperm directly into a female’s mantle cavity.49 These modified arms vary in appearance – resembling syringes, spoons or even toast racks.50 Argonauts – the octopuses that float around water in their paper-like shell constructions – don’t always just deliver the sperm packet inside the female, they often leave their whole hectocotylus with her.51

This adaptation is particularly useful for protection, as many female octopuses are known to often consume their mates after copulating: biting, strangling and then eating them.52 Using an extended arm to deliver sperm comes in handy for the sake of protection, since most female octopuses like to take a big hard bite at their mate after the act, strangling and eating them.53 However, not all species follow this gruesome pattern. The larger Pacific striped octopus mates face-to-face in a gentle, less cannibalistic way, suggesting a more nuanced approach to octopus mating than previously thought.

After mating, the lifecycle of octopuses concludes rapidly. Males often die shortly after delivering their sperm: they wander off alone and die in the next weeks (sometimes months). Females, once fertilised, lay thousands of eggs, and dedicate the rest of their life to guarding them obsessively – to the point of their death. While safe-keeping their clutch, mother octopuses stop eating, and their body starts deteriorating from the inside, a death spiral slowly killing them.54 This mechanism is triggered by something inside the animal’s optic glands.55

In many plants and animals, this strategy of dying after mating once is called semelparity. Evolutionary biologists think it maximises a species' ability to pass on its genes. By channelling all of their energy into a single reproductive moment, these animals increase the likelihood of producing one batch of numerous, healthy offspring. The opposite of semelparity is iteroparity, and it's when animals reproduce several times during their lifetime.

One octopus mother in California made headlines for brooding her clutch of eggs for more than four and a half years before the eggs had hatched, giving life to miniature adults ready to forage in plankton until old enough to eat bigger fish.56

Just like squids, most octopuses can squirt ink. When threatened by predators and trying to get away, octopuses can squirt black ink in their faces: the dark liquid is made of a chemical called tyrosinase, which clouds the predator’s vision, disorients them and disrupts their sense of taste and smell.57 The ink is such an irritant that it can end up killing the octopus itself if it doesn’t get away quickly enough.58

Yes, all octopuses are venomous: they can inject toxins into a prey or predator with a small bite from their hard beaks. Although most octopus venom isn’t dangerous to humans, it can be lethal to smaller prey.59

The most venomous octopus species is the blue-ringed octopus – and this does pose a threat to humans.60 This small cephalopod – some species measuring just up to 6cm in size – injects a neurotoxin far more powerful than cyanide, capable of causing a human’s death in a matter of minutes.61 It’s not aggressive, though, and only attacks if provoked. This octopus's deadliness is signalled by vibrant blue rings on its mantle: they’re a warning sign to stay away.

Octopuses were traditionally thought to be solitary creatures, each fending for themselves. But a growing body of research is starting to suggest otherwise.

In Australia, marine biologists discovered up to 30 gloomy octopuses that have built underwater cities – dubbed Octopolis and Octlantis – made of piles of rocks and shells where they gather in groups and share dens.62 Off the coast of California and the coast of Costa Rica, deep-sea expeditions have revealed rare brooding nurseries with several octopuses all clumped together, close to hydrothermal vents.63 The larger Pacific striped octopus, also known as LPSO, is also a particularly social species and can be found living in groups of up to 40 individuals.64 They are also the species that mates beak to beak, and their females do not die after laying their eggs, unlike most.

When scientists gave two California two-spot octopuses MDMA – a drug that induces feelings of euphoria and sociability – the typically asocial species became warm and curious towards each other.65 This behaviour suggests that octopuses might have brain systems similar to humans for social interactions.66

Featured image © Greens and Blues | Shutterstock

Fun fact image © Masaaki Komori | Unsplash

1. “Cephalopods.” 2023. Montereybayaquarium.org. 2023. https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/cephalopods.

2. “Chambered Nautilus.” Montereybayaquarium.org, 2020, www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/chambered-nautilus.

3. Vendetti, Jann. “The Cephalopoda.” Berkeley.edu, 2006, ucmp.berkeley.edu/taxa/inverts/mollusca/cephalopoda.php.

4. Whalen, Christopher D., and Neil H. Landman. “Fossil Coleoid Cephalopod from the Mississippian Bear Gulch Lagerstätte Sheds Light on Early Vampyropod Evolution.” Nature Communications, vol. 13, no. 1, 8 Mar. 2022, www.nature.com/articles/s41467-022-28333-5.pdf, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28333-5.

5. Mock-Bunting, Logan. “Scientists Discover Four New Species of Deep-Sea Octopus.” Schmidt Ocean Institute, 16 Jan. 2024, schmidtocean.org/scientists-discover-four-new-species-of-deep-sea-octopus/.

6. “WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Octopus Wolfi (Wülker, 1913).” Marinespecies.org, 2024, www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=342047. Accessed 24 Sept. 2024.

7. Rudolph, Nichole. “Octopus Joubini.” Animal Diversity Web, 2002, animaldiversity.org/accounts/Octopus_joubini/.

8. Quaglia, Sofia. “It Looks like a Shell, but an Octopus and 40,000 Eggs Live Inside.” The New York Times, 5 Nov. 2022, www.nytimes.com/2022/11/05/science/octopus-shell-argonaut.html.

9. “The Glass Octopus Is See-through and Spectacular.” Ocean Conservancy, 15 July 2021, oceanconservancy.org/blog/2021/07/15/glass-octopus/.

10. ---. “Scientists Discover New Deep-Sea Octopus Nursery in Costa Rica.” Schmidt Ocean Institute, 28 June 2023, schmidtocean.org/scientists-discover-new-deep-sea-octopus-nurseries-in-costa-rica/.

11. Oceana. “Dumbo Octopus.” Oceana, oceana.org/marine-life/dumbo-octopus/.

12. Kier, William M. “The Musculature of Coleoid Cephalopod Arms and Tentacles.” Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, vol. 4, 18 Feb. 2016, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2016.00010.

13. “Arms vs. Tentacles | Science and the Sea.” Scienceandthesea.org, 2023, www.scienceandthesea.org/program/arms-vs-tentacles#:~:text=An%20arm%20i….

14. Kennedy, E. B. Lane, et al. “Octopus Arms Exhibit Exceptional Flexibility.” Scientific Reports, vol. 10, no. 1, 30 Nov. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77873-7.

15. van Giesen, Lena, et al. “Molecular Basis of Chemotactile Sensation in Octopus.” Cell, vol. 183, no. 3, Oct. 2020, pp. 594-604.e14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.008;

Barbara, University of California-Santa. “Study Demonstrates That Octopus’s Skin Possesses Same Cellular Mechanism for Detecting Light as Its Eyes Do.” Phys.org, phys.org/news/2015-05-octopus-skin-cellular-mechanism-eyes.html;

16. Nuwer, Rachel. “Severed Octopus Arms Have a Mind of Their Own.” Smithsonian Magazine, www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/severed-octopus-arms-have-a-mind-of-t…;

Fossati, Sara Maria, et al. “Octopus Arm Regeneration: Role of Acetylcholinesterase during Morphological Modification.” Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, vol. 447, 1 Sept. 2013, pp. 93–99, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022098113000671?casa_token=…, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2013.02.015.

17. Nahmad-Rohen, Luis, et al. “The Colours of Octopus: Using Spectral Data to Measure Octopus Camouflage.” Vision, vol. 6, no. 4, 22 Sept. 2022, p. 59, https://doi.org/10.3390/vision6040059.

18. Fox Meyer. 2019. “How Octopuses and Squids Change Color.” Si.edu. March 29, 2019. https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/invertebrates/how-octopuses-and-squids-….

19. Nahmad-Rohen, Luis, et al. “The Colours of Octopus: Using Spectral Data to Measure Octopus Camouflage.” Vision, vol. 6, no. 4, 22 Sept. 2022, p. 59, https://doi.org/10.3390/vision6040059.

20. News, Opening Hours Mon-Wed: 9am-9pm Thurs-Sun: 9am-5pm during February 2024 Address 1 William StreetSydney NSW 2010 Australia Phone +61 2 9320 6000 www australian museum Copyright © 2024 The Australian Museum ABN 85 407 224 698 View Museum. n.d. “Southern Keeled Octopus.” The Australian Museum. https://australian.museum/learn/animals/molluscs/southern-keeled-octopu….

21. Marinebio. 2017. “Mimic Octopuses ~ MarineBio Conservation Society.” Marine Bio. 2017. https://www.marinebio.org/species/mimic-octopuses/thaumoctopus-mimicus/.

22. Getty Images TV. 2017. “Mimic Octopus: Master of Disguise.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wos8kouz810.

23. 2017b. “Stretchable Surfaces with Programmable 3D Texture Morphing for Synthetic Camouflaging Skins.” Science 358 (6360): 210–14. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan5627.

24. “Octopus | National Wildlife Federation.” 2024b. National Wildlife Federation. 2024. https://www.nwf.org/Educational-Resources/Wildlife-Guide/Invertebrates/….

25. Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. n.d. “Octopus Movement.” Teara.govt.nz. https://teara.govt.nz/en/video/7906/octopus-movement#:~:text=Octopus%20….

26. 2015b. “Octopus Movement: Push Right, Go Left.” Current Biology 25 (9): R366–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.066.

27. 2009c. “Defensive Tool Use in a Coconut-Carrying Octopus.” Current Biology 19 (23): R1069–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.052.

28. Altman, J. S., and M. Nixon. 2009. “Use of the Beaks and Raduala by Octopus Vulgaris in Feeding.” Journal of Zoology 161 (1): 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1970.tb02167.x;

29. 2015b. “Octopus Movement: Push Right, Go Left.” Current Biology 25 (9): R366–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.066.

30. “What Does an Octopus Eat?” 2023. American Oceans. June 16, 2023. https://www.americanoceans.org/facts/what-do-octopus-eat/#:~:text=Octop….

31. “Circulatory System.” 2009. Brown.edu. May 11, 2009. https://charlotte.neuro.brown.edu/~sheinb/octopus/documents/43.html;

Wells, M. J., and P. J. S. Smith. 1987. “The Performance of the Octopus Circulatory System: A Triumph of Engineering over Design.” Experientia 43 (5): 487–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02143577.

32. When you give an octopus a go prohttps://www.sheddaquarium.org/stories/eight-strange-and-wonderful-facts….

33. Schwarcz, Joe. 2018. “Snails, Spiders, and Octopi All Have Blue Blood.” Office for Science and Society. February 15, 2018. https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/did-you-know/snails-spiders-and-octup….

34. “Blue Blood on Ice – How an Antarctic Octopus Survives the Cold.” n.d. Www.biomedcentral.com. https://www.biomedcentral.com/about/press-centre/science-press-releases….

35. 2018. Nhm.ac.uk. 2018. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/octopuses-keep-surprising-us-here-are-ei….

36. Natural History Museum. 2018. “How Brainy Is an Octopus? | Natural History Museum.” YouTube. October 8, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2x1dxoNA3k0&list=TLGGIDDeugoxOnkyNzAyMj….

37. Hochner, Binyamin. 2012. “An Embodied View of Octopus Neurobiology.” Current Biology 22 (20): R887–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.001;

Hendry, Lisa. n.d. “Octopuses Keep Surprising Us - Here Are Eight Examples How.” Www.nhm.ac.uk. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/octopuses-keep-surprising-us-here-are-ei….

38. Godfrey-Smith, Peter. 2016. “The Mind of an Octopus.” Scientific American Mind 28 (1): 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamericanmind0117-62.

39. Sutherland, N. S. 1960. “The Visual Discrimination of Shape by Octopus: Squares and Rectangles.” Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 53 (1): 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0038429;

Richter, Jonas N., Binyamin Hochner, and Michael J. Kuba. 2016. “Pull or Push? Octopuses Solve a Puzzle Problem.” Edited by Daniel Osorio. PLOS ONE 11 (3): e0152048. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152048.

40. “BBC News - Octopus Snatches Coconut and Runs.” 2024. Bbc.co.uk. BBC. 2024. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/8408233.stm.

41. Zarrella, Ilaria, Giovanna Ponte, Elena Baldascino, and Graziano Fiorito. 2015. “Learning and Memory in Octopus Vulgaris: A Case of Biological Plasticity.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 35 (December): 74–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2015.06.012.

42. Kawashima, Sumire, Kaishu Takei, Saki Yoshikawa, Haruhiko Yasumuro, and Yuzuru Ikeda. 2020. “Tropical Octopus Abdopus Aculeatus Can Learn to Recognize Real and Virtual Symbolic Objects.” The Biological Bulletin 238 (1): 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1086/707420.

43. Anderson, Roland C., Jennifer A. Mather, Mathieu Q. Monette, and Stephanie R. M. Zimsen. 2010. “Octopuses (Enteroctopus Dofleini) Recognize Individual Humans.” Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 13 (3): 261–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2010.483892.

44. Fiorito, G., and P. Scotto. 1992. “Observational Learning in Octopus Vulgaris.” Science 256 (5056): 545–47. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.256.5056.545.

45. Medeiros, Sylvia Lima de Souza, Mizziara Marlen Matias de Paiva, Paulo Henrique Lopes, Wilfredo Blanco, Françoise Dantas de Lima, Jaime Bruno Cirne de Oliveira, Inácio Gomes Medeiros, et al. 2021. “Cyclic Alternation of Quiet and Active Sleep States in the Octopus.” IScience 0 (0). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102223.

46. Eric Angel Ramos, Mariam Steinblatt, Rachel Demsey, Diana Reiss, and Marcelo O Magnasco. 2023. “Abnormal Behavioral Episodes Associated with Sleep and Quiescence in Octopus Insularis: Possible Nightmares in a Cephalopod?,” May. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.11.540348.

47. Pophale, Aditi, Kazumichi Shimizu, Tomoyuki Mano, Teresa L. Iglesias, Kerry Martin, Makoto Hiroi, Keishu Asada, et al. 2023. “Wake-like Skin Patterning and Neural Activity during Octopus Sleep.” Nature 619 (7968): 129–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06203-4;

Bugos, Claire. n.d. “Heidi the Snoozing Octopus May Not Be Dreaming after All.” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/heidi-snoozing-octopus-may-no….

48. Mather, Jennifer. 2021. “Octopus Consciousness: The Role of Perceptual Richness.” NeuroSci 2 (3): 276–90. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci2030020.

49. “Hectocotylus | Mollusk Anatomy | Britannica.” n.d. Www.britannica.com. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/science/hectocotylus.

50. Hendry, Lisa. 2018. “Octopuses Keep Surprising Us - Here Are Eight Examples How.” Nhm.ac.uk. 2018. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/octopuses-keep-surprising-us-here-are-ei….

51. Battaglia, P., M. G. Stipa, G. Ammendolia, C. Pedà, P. Consoli, F. Andaloro, and T. Romeo. 2021. “When Nature Continues to Surprise: Observations of the Hectocotylus of Argonauta Argo, Linnaeus 1758.” The European Zoological Journal 88 (1): 980–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750263.2021.1970260.

52. Huffard, Christine L., and Mike Bartick. 2014. “WildWunderpus PhotogenicusandOctopus Cyaneaemploy Asphyxiating ‘Constricting’ in Interactions with Other Octopuses.” Molluscan Research 35 (1): 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13235818.2014.909558.

53. “6 Animals That Eat Their Mates | Britannica.” n.d. Www.britannica.com. Accessed April 25, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/list/6-animals-that-eat-their-mates#:~:text=…;

2014b. “WildWunderpus PhotogenicusandOctopus Cyaneaemploy Asphyxiating ‘Constricting’ in Interactions with Other Octopuses.” Molluscan Research 35 (1): 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13235818.2014.909558.

54. Wood, Matt. 2015. “ the Grim, Final Days of a Mother Octopus.” Uchicagomedicine.org. UChicago Medicine. 2015. https://www.uchicagomedicine.org/forefront/biological-sciences-articles….

55. Wang, Z. Yan, Melissa R. Pergande, Clifton W. Ragsdale, and Stephanie M. Cologna. 2022. “Steroid Hormones of the Octopus Self-Destruct System.” Current Biology 32 (11): 2572-2579.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.04.043.

56. Imbler, Sabrina. 2022. “The ‘Mother of the Year’ Who Starved for 53 Months.” The Atlantic. December 5, 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2022/12/pacific-octopus-vig….

57. Derby, Charles. 2014. “Cephalopod Ink: Production, Chemistry, Functions and Applications.” Marine Drugs 12 (5): 2700–2730. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12052700.

58. Frey, Michelle. 2022. “Why Do Cephalopods Use Ink?” Ocean Conservancy. June 23, 2022. https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2022/06/23/cephalopods-ink/.

59. News, NBC. 2009. “All Octopuses Are Venomous.” NBC News. NBC News. April 16, 2009. https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna30248367.

60. Osterloff, Emily. n.d. “The Blue-Ringed Octopus: Small, Vibrant and Deadly.” Www.nhm.ac.uk. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/blue-ringed-octopus-small-vibrant-deadly….

61. “Blue Ringed Octopus | AIMS.” n.d. Www.aims.gov.au. https://www.aims.gov.au/docs/projectnet/blue-ringed-octopus.html#:~:tex…;

Spencer, Erin. 2018. “The Blue-Ringed Octopus: Small but Deadly - Ocean Conservancy.” Ocean Conservancy. September 13, 2018. https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2017/03/13/the-blue-ringed-octopus-sm….

62 . Skokstad, Erik, “Scientists discover and underwater city full of gloomy octopuses”https://www.science.org/content/article/scientists-discover-underwater-…

63. 2023b. “Scientists Discover New Deep-Sea Octopus Nursery in Costa Rica.” Schmidt Ocean Institute. June 28, 2023. https://schmidtocean.org/scientists-discover-new-deep-sea-octopus-nurse….

64. #author.fullName}. n.d. “Octopuses Were Thought to Be Solitary until a Social Species Turned Up.” New Scientist. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg24432610-400-octopuses-were-thou….

65. Nuwer, Rachel. 2018. “Rolling under the Sea: Scientists Gave Octopuses Ecstasy to Study Social Behavior.” Scientific American, December. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican1218-18.

66. Edsinger, Eric, and Gül Dölen. 2018. “A Conserved Role for Serotonergic Neurotransmission in Mediating Social Behavior in Octopus.” Current Biology 28 (19): 3136-3142.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.061.

Fry

Consortium

Mainly fish, marine invertebrates, crustaceans and shellfish

Mainly humans, fish, seals, whales, birds, and sea otters

Common octopus 1-2 years, some other species up to 5 years

Varies greatly depending on species, as small as 2cm to as large as stretching to 5m from arm to arm

Varies greatly depending on species, as light as less than a gram to as hefty 20-50kg, with the heaviest recorded individual weighing 70kg

Octopuses have eight arms – not tentacles. And each arm is capable of acting autonomously.