BBC Earth Podcast

Close your eyes and open your ears

Intimate stories and surprising truths about nature, science and the human experience in a podcast the size of the planet.

Animals

Oxytocin and its cuddly effects.

Oxytocin is a mammalian hormone responsible for the sensation of love. It’s involved in social recognition and bonding, and is believed to play a part in the formation of trust between people.

Oxytocin is what makes mother-baby bonding so powerful – hence it being known as the ‘cuddle chemical’ and ‘love hormone’.

But it’s also been found that the males of many species have oxytocin-led responses to early parenting – some of which are pretty surprising.

Dogs’ bodies produce oxytocin when in the presence of their human counterparts – and they get a big burst of it every time they make eye contact with their bonded humans.

When a dog’s brain is flooded with the hormone, it’s better able to follow the social cues of its owners. And the longer a dog maintains its owners’ gaze, the more elevated the levels of oxytocin released.

In fact, dog levels of oxytocin are on average five times higher than those of cats.

Marmoset and tamarin monkeys from Central and South America live in family social groups. When a female gets pregnant, the father picks up on her social cues and actually gains weight: he’ll start packing on the pounds as soon as she’s getting bigger throughout the pregnancy.

At this time, the fathers have different hormones – oxytocin, oestrogen and prolactin, which is linked to breastfeeding – that make him more maternal once the infant arrives. The marmosets have nipples right under their arms, and the father experiences enlargement of these when his mate is pregnant.

It seems that just a few tweaks of hormones can have a profound effect on what we think of as male and female.

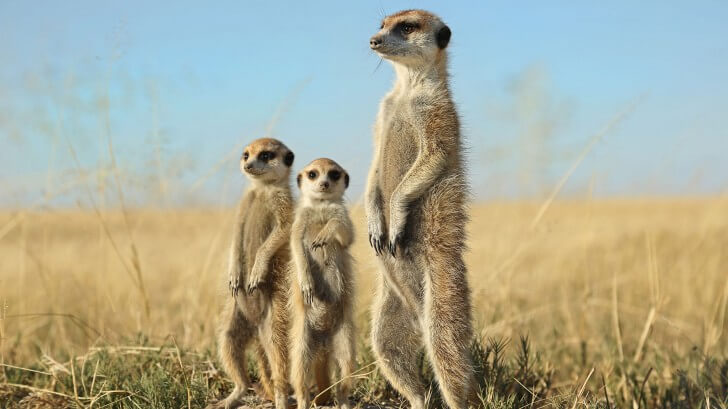

Meerkats are textbook examples of cooperative social creatures. They live in groups of up to 50, helping each other to dig and guard burrows. They babysit, feed and teach one another’s pups. But they can be made to be even more cooperative. How? Simples.

Two University of Cambridge professors worked with meercats from four different groups at South Africa’s Kuruman River Reserve to see the effect that oxytocin would have.

Those dosed up with the ‘love drug’ spent more time guarding and burrowing, were less aggressive, spent more time with pups and gave them a larger share of food. All at a personal cost: the oxytocin-loaded meerkats spent less time foraging for themselves, and thus ate less food.

The burying beetle is a rare example of an insect that shows parental care.

In this species found in the UK, both the female and the male stay behind and look after the young. When the female is pregnant, the beetles will leave a space for larvae in a dead mouse they have buried for food and nesting. This is for their larvae to crawl to when they hatch.

The larvae will beg for food – also quite unusual for insects. When hungry, they use their small legs to ‘tickle’ their parents, who will then regurgitate digested food for them.

Prairie voles are monogamous, and males often display parental care and protect their mates. Meadow voles, on the other hand, are polygynous, wherein males mate with many females and they display very little, if any, parental care, and rarely protect their mates.

A comparison of these two species has shed light on why this is the case. In prairie voles, individuals have many more vasopressin receptors in the ventral palladum area of their brains than meadow voles do – and vasopressin is related to ‘cuddle chemical’ oxytocin.

Such variations in a section of gene coding are also believed to determine whether human males are naturally commitment-phobes or devoted husbands.

In studies of suckling rats, those that received warmth and touch when feeding had lower blood-pressure levels than young individuals that did not receive any form of touch from their parents. This was found to be a result of an increased vagal nerve tone, meaning that they had had higher parasympathetic nervous response and lower sympathetic nervous response to stimulus, resulting in a lower stress response.

Oxytocin is found to have a lowering effect on blood pressure in not only rats, but also humans. So we’re not the only ones that benefit from a cuddle and comfort food.

Featured image by Yuki Cheung, EyeEm | Getty

Intimate stories and surprising truths about nature, science and the human experience in a podcast the size of the planet.