BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

Plants

Some of the planets most unusual plants and animals have become allies…

We all know about the special relationship between dogs and humans, but perhaps not so well-known are the many symbiotic relationships between plants and animals. An obvious example of this is the pairing of bees and flowers; the bees collect nectar as food, but also pick up pollen, which then pollinates the next flower the bees visit.1 It’s a win-win situation for both species, and when it occurs, this type of symbiotic relationship, known as ‘mutualism’, often transpires in the most unlikely forms.

From the acacia ant whose home doubles up as supper, to the Lilford wall lizard's curious relationship with a pitcher plant, our natural world is filled with weird and wonderful relationships...

Discover more astonishing plant-animal relationships with new Sir David Attenborough series The Green Planet, which explores the wondrous interconnected world of plants. Find out where to watch in your region here. 🌱

The flowers of the ‘7-hour flower’ (Merinthopodium neuranthom) are pollinated by Underwood's Long-tongued Bat (Hylonycteris underwoodi). The bat is the plant's primary pollinator, and the plant's nectar its bats main source of food. Endemic to Central America, these bats typically reside in forested, tropical regions. These elusive creatures, come out from their roosts at dusk to forage for nectar in these mutualistic relationships.2

In the dry, tropical forests of Central America, the Bullhorn Acacia tree thrives – and it also provides a home to one of the fiercest species of Ant in the region, Pseudomyrmex Ferruginea. These stinging ants nest in the hollow thorns of the trees, but they don’t just get room and board from their host, instead they get the fully-inclusive benefit of a continual source of food from the plant’s nectar. In return, the ants vigilantly protect the tree from ravaging insects, grazing mammals, and competing plants, like epiphytic vines. Studies found that the presence of this particular type of ant also reduced leaf damage from microbial pathogens. They somehow boosts the trees’ immune system; they display an increased concentration of salicylic acid, a plant hormone important in the defence against pathogens. Quite how this is achieved is unclear, but what is evident is that other trees – inhabited by parasitic, rather than these symbiotic, ants – suffer more damage from herbivores and pathogens. And that just goes to show just how uniquely beneficial to each other these two species have become.3,4

Located in the Spanish Balearic Islands is a lizard species known as Lilford’s wall lizard (Podarcis lilfordi). It has become an ally of one of the planet's strangest plants, the dead horse arum (Helicodiceros muscivorus), known as such because it looks and smells like rotting horse meat. The plant exhibits its revolting masquerade to lure and trap flies in its flowering flesh – it even generates heat to appear even more enticing. The cold-blooded lizards find an easy meal in the trapped flies, but more importantly, they have learned that if they crack open the hard seed heads on the plant, the soft berries inside are also a tasty food source. Not so good for the plant then? Actually yes, as once passed through the gut of the lizards the seeds are twice as likely to germinate. Researchers who studied this phenomenon from 1999 to 2005 found that the population of this relatively rare plant increased from less than 5,000 individual plants per hectare to a healthy 30,000 plants per hectare.5

Carnivorous plants like Borneo’s pitcher plant (Nepenthes lowii) trap and kill insects and are similarly as strange and unattractive to us as the dead horse arum. In light of this, you might be surprised to learn that the local population of tree shrews have no qualms about eagerly stepping into the open snare of the plants jaws in order to partake of its syrupy nectar. This gives them a tasty meal, but the plant isn’t looking to trap the shrews for a meal in return, it is actually hoping the shrew will use the handy ‘toilet facilities’ and defecate into its stomach. This is because the shrew’s faeces are rich in nutrients, which is the meal the plant is looking for.6 The local Woolly bat population has a similar relationship with another of Borneo’s pitcher plants Nepenthes hemsleyana. In return for a chance to roost in the jaws of the flower, the bats poop into the belly of the plant, providing it with a highly nutritious meal. They have nothing to fear from taking a well-earned break inside the mouthpiece of this deadly host.7

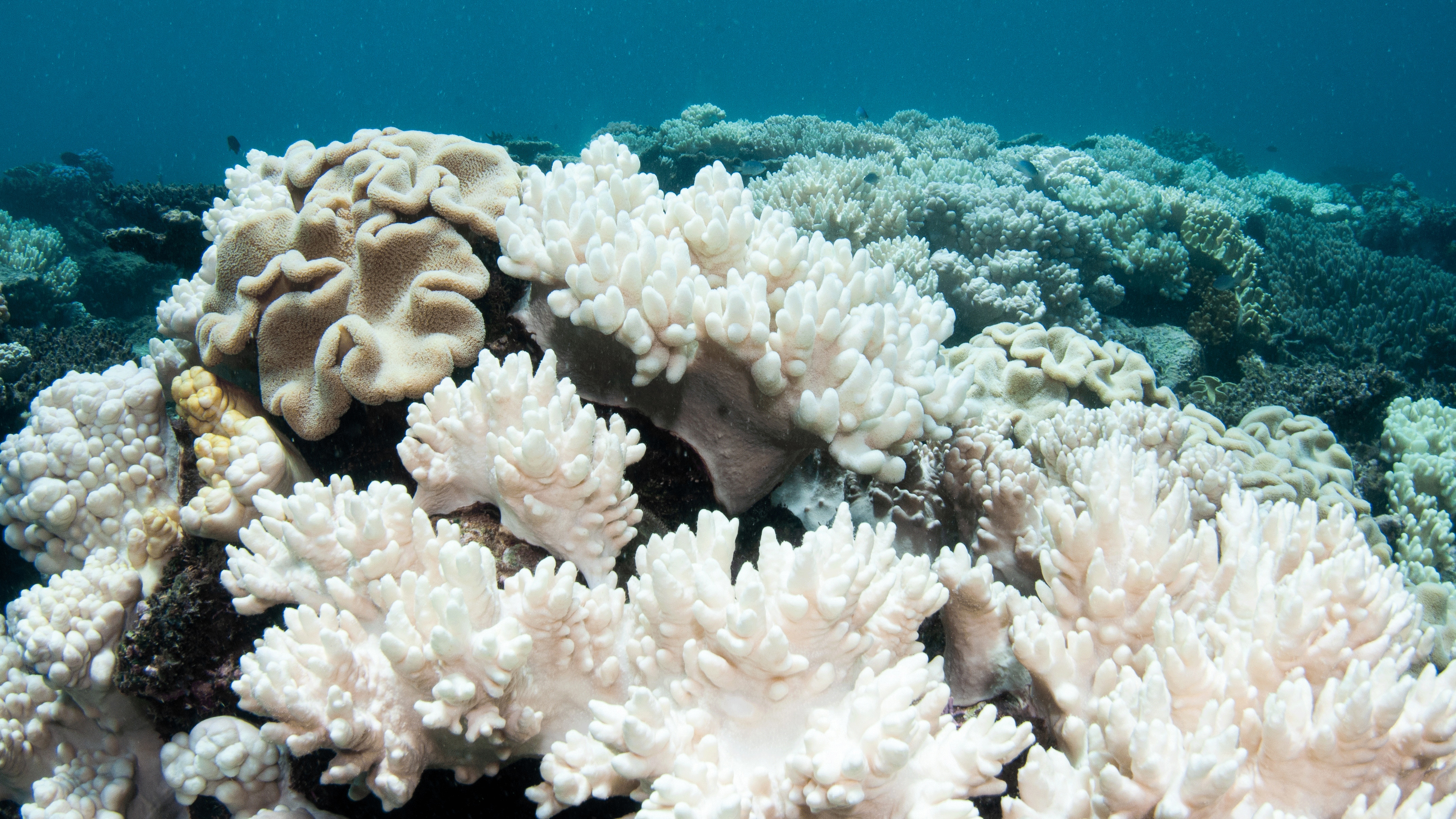

And talking of hosts, the tiniest of algae in the ocean have one of the most important mutualistic relationships on Earth, by being the welcome guests of reef-building corals. These algae (zooxanthellae) live in the coral’s tissue, where they feed on compounds that the algae need to photosynthesise. Meanwhile, the coral uses the products of the algae photosynthesis - namely glucose, glycerol and amino acids - to produce proteins, fats, carbohydrates, and calcium carbonate. The algae also produce oxygen and help the coral expel waste. In tropical waters where nutrients are often scarce, the co-existence of these two species, and their efficient sharing and processing of nutrients, results in healthy corals, the building blocks of the biggest biological structures on the planet.8 The wonderful colours and amazing bio-diverse underwater worlds of the tropical coral reefs are a stunning product of this amazing symbiotic pairing of plant and animal.9,10

Across our planet, the most amazing plant and animal combinations are working in harmony with each other. However, like many things in the natural world, large numbers of these relationships are now under threat from climate change and other consequences of human activity. Along with habitat loss and the use of pesticides, climate change has played havoc with bee populations – and as with all delicately balanced ecosystems, this fluctuation has a knock-on effect for everything the bees interact with, including the flowers and plants they pollinate.11

Similarly, corals are rapidly depleting, due to changes in water temperature and acidity. The colour of the coral comes from the zooxanthellae, the algae that live inside them. But when the environment changes, such as a rise in sea temperature, the polyps that make up coral become stressed and eject their microscopic algae partners. The corals lose their colour and become bleached, and when this happens it is only a matter of time before the coral eventually dies. In fact, a recent analysis observed that since the 1950s we have already lost up to half of our precious coral reefs forever, including the biodynamic ecosystems they support.12

And it is not just climate change that can affect the delicate balance these relationships require. In the case of the dead horse arum and the Lilford’s wall lizard, the introduction of cats and rats to the Balearic Isles has drastically affected the archipelago’s lizard population, so it is now in decline. This in turn can only lead to a negative effect on the population of its bizarre but strangely alluring plant partner.

As more and more is learned about these fascinating interactions in the natural world, more is being done to safeguard – and restore - them. For instance, scientists in Florida have taken samples of corals that have survived environment changes, then grown them in batches in nurseries, before re-planting them on the damaged reef. In the Bahamas, biologists have gone one step further with this exploration of survival of the fittest – they’re searching for the specific gene responsible for some corals surviving temperature extremes. The intention is to then breed more resilient coral.

Protecting these instances of mutualism is beneficial to humans, too. Coral reefs help protect land from the impact of hurricanes and provide livelihoods from the touristic opportunities they provide.13 While humans depend on plants, just as plants depend on pollinators – so it’s in our best interests to ensure their survival. UK and Irish governments have established ‘National Pollinator Strategies’, to help combat the decline in pollinators, so vital to food production and environmental diversity.14,15

In terms of tackling the root of the problem, a new global agreement on climate change was struck in November 2021. The aim is to cut the emissions of carbon dioxide – one of the greenhouse cases that causes global warming – until net zero is reached by the middle of the century. However, some campaigners fear this is not enough.16

Ultimately, the survival of these species and their unique relationships depend upon a healthy planet. And without the right conditions, they are under severe threat. A global effort is needed to protect these instances of mutualism – and more broadly – the future of our planet.

Discover more unlikely plant-animal relationships with new Sir David Attenborough series The Green Planet, which explores the wondrous interconnected world of plants. Find out where to watch in your region here. 🌱

Featured image © BBC Studios NHU

References:

1. The Importance of Bees, 2. Underwood's long-tongued bat 3. The Acacia Ant, 4. The Bullhorn Acacia 5. Lilford's wall lizard, 6. A Shrew on the Loo, 7. Woolly bats and Pitcher Plants, 8. The Largest Structures of Biological Origin on Earth, 9. Coral Building, 10. Zooxanthellae 11. Decline of the Pollinators, 12. Coral Loss, 13. Restoring the Coral Reef, 14. National Pollinator Strategies, 15. England National Pollinator Strategy, 16. The COP26 Agreement