BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

Oceans

The plight of the North Atlantic right whale, a species with just 450 individuals left in its population, just got even worse.

After a disastrous 2017, in which at least 17 North Atlantic right whale deaths were recorded, it has emerged that no newborn calves have been sighted since.

This lack of offspring has scientists who study these majestic creatures worried. Is there anything that we can do to encourage right whales to reproduce again?

It’s a pertinent question for Moira Brown at the New England Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life. Two of the adult females that died last year were just on the cusp of reproductive age, she points out. That leaves a total of around 100 adult females in the North Atlantic right whale population.

“That’s what the future of this population is resting on – 100 adult females is not a lot of animals and these things can go bad pretty quickly,” says Brown.

Take the example of the critically endangered Vaquita porpoise – a species that had 600 individuals about 20 years ago. Now, it numbers just 30. The fragility of small populations in marine mammal species is well known. This is why some scientists are estimating that the North Atlantic right whale could go extinct in as little as 23 years, unless its fortunes improve.

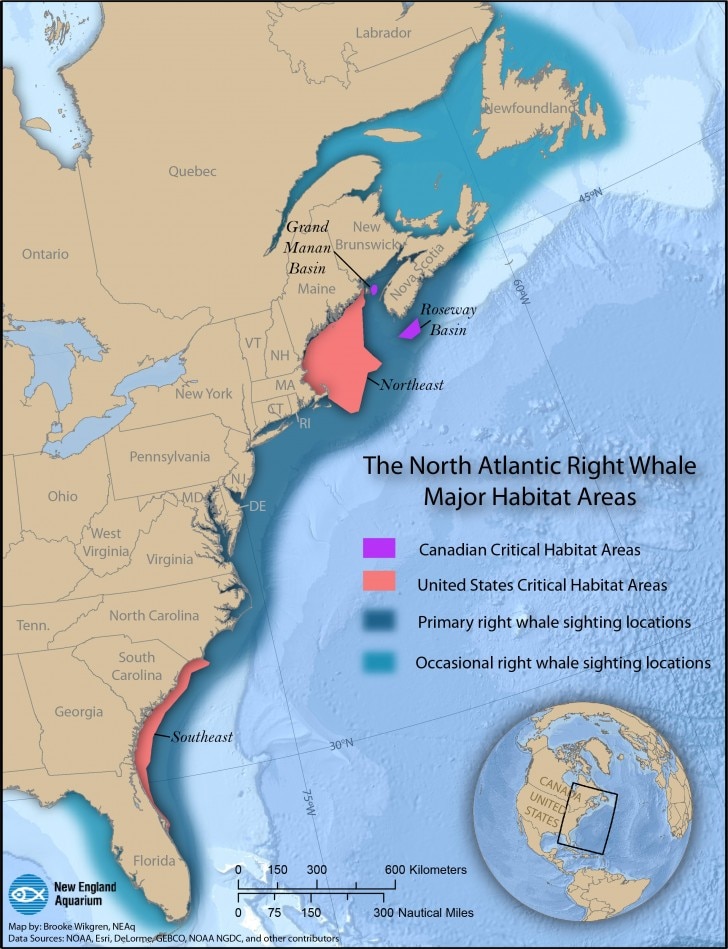

The whales usually breed in waters off the south eastern coast of the US, near Florida and Georgia, however, they feed elsewhere. Their favourite haunts change from time to time, last year for example, more than expected were sighted in Canada’s Gulf of St Lawrence. There were several reports of right whales becoming entangled in fishing gear there and some of those entanglements proved fatal. But even entanglements that didn’t kill could have had a significant impact on the species’ ability to reproduce.

That’s what the future of this population is resting on – 100 adult females is not a lot of animals and these things can go bad pretty quickly,”

Although a few fishing ropes might not seem like a big deal to some, they are surprisingly heavy, tough pieces of material. And when wrapped around a whale’s body, they cause significant mobility issues and increase drag when swimming through the water.

Recently, whale rescuers have been trying to disentangle a well known female North Atlantic right whale, nicknamed Kleenex, that had been entangled for at least four years.

Michael Moore at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) has studied the long-term effects of such episodes.

“For a female right whale, what can you give up if you’re running out of energy? The answer is you don’t get pregnant,” he says.

Moore and other whale scientists generally agree: the most significant boost we can give to this species is to reduce the likelihood of entanglements, get out of their way, and hope that they have enough energy to breed.

The Canadian government recently announced special measures in this vein, including opening and closing the snow crab fishing season earlier than usual this year. The traps used to catch snow crabs are often tethered to ropes linking them to buoys floating on the sea surface. That of course creates a long line through the water column in which a whale could get caught.

One idea is to use ropes adapted to break when a certain amount of pressure is exerted on them, explains Phil Hamilton, also at the New England Aquarium's Anderson Cabot Center.

“Basically they just cut the [rope] and they put these sleeves over either end that are designed to break at 1,700 lbs [of pressure],” he explains. “The sleeves are like a dollar apiece.”

A study authored by Hamilton’s colleagues estimated that such measures could reduce life-threatening whale entanglements by up to 72%.

Another possibility is to use fishing gear that can rise to the surface without having to be dragged up by rope – WHOI and the Anderson Cabot Center have been working on this idea together.

But is there anything more interventionist humans can do to encourage or induce reproduction in the species? The answer, according to Moore, Hamilton and Brown is a resounding “no”. These are large marine mammals, with huge ranges. There’s no obvious beneficial way in which we could interfere with them. They also have big appetites so even something like trying to boost their food resources artificially would come at a gargantuan cost.

It would probably be cheaper to buy out the fishing companies and remove ropes from the water in areas where the whales congregate, suggests Moore.

Hamilton does have one other idea, though. He points out that whales are often stressed by excessive noise in the oceans – mainly from shipping or industrial work. If we could lower these noise levels, that might have a positive impact on their propensity to breed, though that’s not a given.

There is still hope for North Atlantic right whales. The population has, in fact, been lower than it is today and increased, says Brown. In 1990 there were only about 270 known individuals. This rose over the following 20 years – and even endured periods where breeding levels were very low. In 2000 just one calf was sighted. “The very next year we had 31,” says Brown, pointing out how unpredictable the species can be.

And Hamilton says there’s an outside chance that one or two calves were born in recent months, perhaps in unusual calving grounds, and we just haven’t detected them yet.

“Personally I still hold out hope that one or two calves will be detected this spring and summer,” he says.

"Given the species’ fluctuating population history, there is plenty of reason to believe that helpful measures we take now can have the intended effect." adds Brown.

“This population has bounced back before,” she says. “So nobody’s giving up on them.”

Featured image © Wildest Animal | Getty