BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

Landscapes

Here is our guide to where on Earth you can experience a little bit of life on Mars.

The soil is reddish brown, flecked with black volcanic sand. Dark basalt rocks stud the arid valleys and escarpments of this alien place. And in the midst of this bleak landscape stands Claire Cousins. She is here to study the rocks, turning sensitive scientific cameras onto them in the hope of finding signs of life on another world – Mars. Except she isn’t on the Red Planet at all. She is still on Earth. Northern Iceland to be more precise.

Cousins is one of hundreds of planetary scientists who travel to far flung parts of the globe in the hope of getting a taste of Mars here on Earth. These "Mars analogues", as they are known, help to test equipment, hone scientific experiments and even train astronauts for future missions to the Martian surface.

But they also give an opportunity to taste what it might actually be like to walk on the surface of the Red Planet. Here is our guide to where on Earth you can experience a little bit of life on Mars.

At the heart the Atacama Desert, close to the abandoned mining town of Yungay to the south of the city of Antofagasta in Chile, is one of the most Mars-like regions in the world. It is one of the driest spots on Earth, and it can go decades without any rain. On average, it receives less than 10mm of rain per year, making the soil hyperarid.

"Superficially, it looks very similar to modern day Mars," says Cousins, who is a senior lecturer at the University of St Andrews. "Today Mars is very a cold, desolate, rock desert."

While the temperatures in the Atacama don't drop as low as they do on Mars – they range from between 0°C at night and 40°C in the day while on the Red Planet they range from -195°C to 20°C – its soil shares the rusty colour found on Mars.

It is often used to put robotic equipment through its paces before it is used on missions to the Red Planet. Instruments used on the Viking 1, Viking 2, and Phoenix Mars landers along with the European Space Agency’s future ExoMars Rover have all been tested there.

Earlier this year, scientists from Nasa and Carnegie Mellon University in the US tested an autonomous robot that drilled down beneath the Atacama Desert's surface and recovered strange underground, salt-resistant bacteria, perhaps providing cludes of what life might still exist on Mars.

Getting there: According to the European Space Agency’s Catalogue of Planetary Analogues, the nearest airport is Antofagasta in Chile.

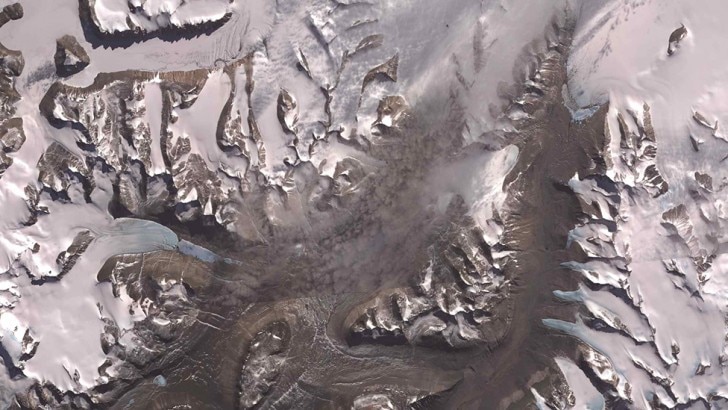

A row of snow-free valleys in the world’s coldest continent, the McMurdo Dry Valleys of East Antarctica can certainly contend with Mars for being inhospitable. The average temperatures through the year sit between -15°C to -30°C, according to a study of valley floor climate observations, and parts may not have seen rain for millions of years. What water does fall there as snow – equivalent to 7-11mm of rain annually according to some studies – is quickly lost through a process known as sublimation, where the ice turns directly into gas. Something similar happens on Mars to the carbon dioxide frosts that form on its soil and may be responsible for creating distinctive gully formations on the Red Planet, according to a science report on Extreme decay of meteoric beryllium-10.

In Antarctica, the Dry Valleys are also battered by hurricane force winds of up to 320km per hour (223mph), more than three times faster than the maximum wind speeds on Mars. In both places, however, the winds can whip up the bone-dry soil into dust clouds – like the kind that finally ended the 15 year mission of the Opportunity Rover on the Red Planet.

In the summer months, the McMurdo Dry Valleys are also bombarded to high levels of ultraviolet radiation from the Sun, according to this study entitled On the rocks. But despite these harsh conditions, life can still be found in these freezing cold, desert valleys.

Tiny bacteria that can convert sunlight into energy have been found living under lumps of quartz rock in the valleys. The quartz helps to filter out the worst of the ultraviolet light, while still allowing enough light through to the green bacteria for them to grow. Astrobiologists believe that if life is found on Mars, it may well be living a similarly precarious existence.

But perhaps the most alien like feature of Antarctica’s Dry Valleys is to be found at the point where a glacier spills through the mountains at the head of Taylor Valley. Here iron-oxide tainted brine flows from the tongue of the glacier, staining it blood red.

Getting there: For those looking to visit, access is tricky as it requires either a trip on a military aircraft or a research vessel. However, there are seven semi-permanent scientific field camps in the Dry Valleys.

"Today Mars is very a cold, desolate, rock desert."

Deep in the Canyonlands of the Colorado plateau, straddling four states in the southwest USA, is a series of outcrops that date back to the Late-Jurassic period. The silt and sand left by ancient marshes have formed a orange-red landscape in the Utah desert that looks hauntingly similar to that on Mars.

The site, which lies close to the town of Hanksville, was recently used by the Canadian Space Agency and British scientists to test cameras and other instruments that could eventually be sent to Mars on ESA’s Exomars rover. Images beamed back from the rover to a mission control centre in the UK showed a rocky landscape covered in loose pebbles and dry cracked soil, similar to those sent back from robots actually on the surface of Mars.

Getting there: Hanksville has its own airport suitable for light aircraft, but it is also possible to fly into Salt Lake City and travel by road. The site is just 11km (7.2 miles) north west of Hanksville.

Formed by a now dormant volcano around three million years ago, Tenerife in the Canary Islands may be a popular holiday island, but it is also a good place to get a glimpse of Martian life. The slopes of Mount Teide, the 3,718m high volcano at the heart of the island, is dotted with hollow lava tubes and volcanic caves similar to those that astrobiologists believe could be potential habitats for life on Mars.

"Evidence for the existence of Martian caves such as long lava channels and lines of pits have been identified from orbiting spacecraft," writes Monica Grady, a professor of planetary science at the Open University in the Catalogue of Planetary Analogues. These caves could hold water and also shelter life from the harsh ultraviolet light from the Sun that scours the Martian surface.

"The caves in Teide national park are an ideal terrestrial analogue of Martian caves," says Grady.

Getting there: A public road runs through the El Teide National Park and it is possible to take tours that visit some of the lava tubes. A cable car will take passengers on an eight minute journey up the side of the mountain, although access to many parts of the summit and slopes are by special permission only and require permits.

As one of the most geologically active parts of the world, Iceland can provide a taste of Mars both as it is today and as it was billions of years ago. The highlands that cover most of the interior of Iceland mostly consist of uninhabited volcanic desert.

The dark volcanic soil holds little water and so little life is able to grow there. Large eruptions in the past also flooded entire valleys with lava, something that occured on Mars too.

"Geologically speaking, the rock types there are chemically very similar to Mars and the terrain is also very similar," says Claire Cousins, who has been been testing the PanCam instrument for ESA's ExoMars rover. "It really feels like you are standing on the surface of another planet."

But Iceland also gives scientists the chance to look at how Mars might have looked four billion years ago too. The active hot springs that dot island are a "natural laboratory" that produce similar conditions to those thought to have existed on Mars early in its history.

"We can use these to look at the type of organisms and chemistry that existed on early Mars," says Cousins. "We find chemolithotrophs here - microbes that eat rocks and minerals. They are extremely hardy. It might just be what lived on Mars in its early history."

Getting there: While Iceland has an extensive road network connecting most of the main geological attractions for tourists, getting to the remote volcanic areas in the highlands will often require considerable hiking on rough terrain.

The stony deserts of central and western Australia have dry, red earth that are littered with large dunes and impact craters similar to those found on Mars. Weathering of the landscape here by the wind and streams has been used to understand some of the features seen in pictures from the Red Planet.

"Pilbara is particularly interesting as it has some of the most ancient rocks on Earth," says Claire Cousins. "These are some of the closest in age to the rocks on Mars that we have."

Some of the oldest evidence for life on Earth have been found fossilised in 3.4 billion year-old sandstones in the Pilbara region. Tiny mineralised spheres found on an ancient beach are thought to have belonged to an ancient bacteria that lived off sulphur.

Similar structures found in Martian meteorite samples have sparked fierce debate about whether they too could be the fossilised remains of bacterial life on the Red Planet.

Getting there: A vast area that is bigger than California and Indiana combined, Pilbara is sparsely populated. It is possible to fly to Port Hedland or Newman in the North and then travel by road from there.

A village nestled amongst the rolling green hills of the North York Moors, it not a likely location to find somewhere similar to Mars. But beneath the village of Boulby is a potash and salt mine that is the perfect analogue for parts of the Martian environment.

Covering the roof and walls of the mines tunnels, which lie nearly 1km underground and stretch out beneath the north sea, are polygon-shaped structures similar to those seen in an area of Mars that has been nicknamed the “Giants Causeway” after the region on the north coast of Ireland, as reported in the study, Discovery of columnar jointing on Mars.

Researchers from the University of Leicester and the UK Space Agency have been testing a prototype of the Raman Laser Spectrometre that will be carried on the ExoMars rover to look for the chemical signatures left by living organisms. The salty environment of the mine is extremely hostile to bacteria and is inhabited by specially adapted microbes called halophiles, which may be similar to organisms that could survive on Mars.

Getting there: The village of Boulby itself is easily accessible by road, but getting access to the mine is likely to require special permission from the company that owns it as mining is still in operation there.

This mountainous archipelago on the edge of the Arctic Circle has little in the way of soil or vegetation. The terrain is composed of red sand and gravel. The gullies and alluvial fans left by rivers bare a striking resemblance to features that can be found on Mars. The cold Arctic conditions are also perfect for putting equipment and potential astronauts through their paces.

"I'm lucky enough to see Mars' surface through our rover's eyes every day," says Nicole Schmitz, a planetary geologist with the German Aerospace Center (DLR) who has spent time in Svalbard testing scientific instruments for use on both Nasa’s Curiosity rover and the future ExoMars rover.

"But working in analog environments helps me to understand how difficult working in a challenging environment is. In Svalbard, you wear a thick down suit, and thick gloves. Your range of motion is restricted. You have to climb and carry equipment, repair stuff, and you get tired, cold, and exhausted, but have to function nevertheless. There is no mobile communication network, so you can’t just call for help. You have to work in teams, look out for each other, and use what you have to solve every problem."

Getting there: The largest airport on Svalbard is at Longyearbyen, but to reach some of the more remote parts of the islands requires a boat. It is also wise to take necessary protection against polar bears.

At first glance, Britain’s southern coast is about as far from Mars as you might imagine, but Dorset is home to highly acidic sulphur streams where extreme species of bacteria thrive. One of these streams in St Oswald’s Bay is thought to mimic the conditions that existed billions of years ago on Mars.

The iron rich mineral called goethite transform in the acidic stream into hematite, which is also found on Mars. Scientists believe analysing hematite on Mars for organic matter preserved there may be a good way of finding evidence for life on the Red Planet.

"St Oswald's Bay is a present-day microcosm of middle-aged Mars," says Jonathan Tan, a planetary scientist at Imperial College London. "As the acid streams dry up, like during Mars's 'drying period', they leave goethite minerals behind which preserve fatty acids that act as biological signatures."

Getting there: A short walk from the picturesque coastal village of West Lulworth.

Featured Images © Tobias Titz | Getty