BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

Conservation

When you run this fast, you need space to stretch your legs. But that’s just what the 7,000 or so cheetahs left in the wild don’t have, as wildlife reserves are running out of room.

Can a new approach help humans and cheetahs live side by side?

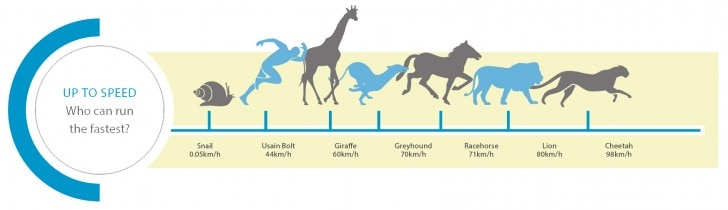

The world record for the fastest 100m is 5.95 seconds. It was set by Sarah, an 11-year-old cheetah from Cincinnati Zoo, in 2012. Put her up against the fastest human on Earth, Usain Bolt – whose 100m record is 9.58 seconds – and she’d be over the finish line, hurtling along at 98km/h, before he was barely into his stride.

With tyre-tread paw pads and running-spike-style claws that, unlike those of other cats, don’t fully retract, cheetahs are made for speed. But it’s the acceleration that cheetahs such as Sarah can achieve that truly astounds: 0 to full speed in three seconds, faster than many a sports car. Every centimetre of their frames, from their large nasal passages that maximise air intake, to their rudder-like tails that help them steer at full pelt, is an adaptation that helps them to explode after their prey like feline bullets. With their compact heads, skinny legs and spring-like spines, they’re living, breathing examples of how nature can rival the greatest achievements of human engineering.

‘It does take your breath away,’ says Dr Sarah Durant of the Zoological Society of London and the Wildlife Conservation Society, who has watched cheetahs hunting for nearly 30 years. The speed comparison she draws is that ‘If you were driving from a slip road onto a motorway, the cheetah could be overtaking you.’

Just 7,100 cheetahs now remain in the wild, according to a new study by Dr Durant and 53 other experts. A hundred years ago that figure was more like 100,000, spread across much of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula and into India. The species has now disappeared from 91 per cent of the area it once inhabited.

Today, most cheetahs – around 4,000 of them – are concentrated in a population that spans six countries in southern Africa: Angola, South Africa, Botswana, Mozambique, Namibia and Zambia. Another 1,400 or so live in an area straddling the Kenya-Tanzania border, while the rest exist as 31 pockets of 200 or so individuals elsewhere in central, southern and eastern Africa as well as Iran, home to the last three groups of Asiatic cheetahs. One of five subspecies (the others are the South African cheetah, Northwest African cheetah, Sudan cheetah and Tanzanian cheetah), these critically endangered cats likely number fewer than 50 in the wild, with just two in captivity.

These numbers are dire, but Durant’s study’s mathematical models suggest they could get a lot worse, perhaps dropping by half again over the next 15 years. Already, Zimbabwe has seen its cheetah population plummet from 1,200 to 170 in the last 16 years – an 85 per cent loss.

To understand why cheetah populations are so fragile, you need to realise how different they are to the robust lions, tigers and leopards of the Panthera genus. On the African plains, lions often steal cheetah kills and devour their cubs – up to 90 per cent die before they reach three months, research shows. In fact, as the sole member of the Acinonyx genus, cheetahs are not much like other big cats at all, Durant says. ‘They have a weird social system where females range across big areas. The males have small territories.’ A female can range over 3,000km² – twice the size of Greater London. One tracked in the Sahara roamed across 1,500km² in just two months. They also like to stay out of each other’s way; you rarely find more than two in any 100km² area and in places like the Sahara, you might only find one per 4,000km.

These huge space requirements mean even the biggest wildlife reserves can only harbour limited numbers – the Serengeti in Tanzania has room for just 300 cheetahs. Over three quarters of the areas they inhabit lie outside protected zones. There, these shy, elusive cats are even harder to monitor and much more at risk. Now Durant is calling for their status to be upgraded from ‘vulnerable’ to ‘endangered’ on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

Cheetahs are particularly vulnerable to losing their habitats to farming and human expansion, which also reduce the numbers of their prey, such as gazelle, antelope and impala. The result makes them more likely to attack livestock and, in turn, be killed by farmers. Cheetahs also make easy targets for poachers outside protected areas. Their spotted skins are coveted throughout Africa, while live cubs can command four-figure sums in the Middle East, where pet cheetahs are status symbols. Most trafficked cubs – around 85 per cent, according to the Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) – fail to survive. Saving cheetahs will clearly take more than just watching over them in wildlife reserves. Nothing short of a whole new approach that encourages humans and cheetahs to live side by side is needed, Durant believes – no mean feat in poor areas where farmers are likely to view them as a threat to their herds.

‘We’re not pretending it’s easy,’ says Durant. Financial incentives for communities that protect wildlife or schemes to allow farmers to charge more for goods from well-conserved areas could be ways forward. Keeping cheetahs away from livestock is another – the CCF says its long-running programme to place guard dogs with Namibian farmers has helped reduce livestock loss from all predators by over 80 per cent, and up to 100 per cent. A change does seem to be in the air. The decision by the 180 nations attending the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora conference in Johannesburg last autumn to stem the illegal live cheetah trade was a hugely positive step and prompted the United Arab Emirates to pass a law banning people from keeping wild animals as pets.

There’s certainly more to do. But the good news is that humans and cheetahs can survive and thrive together if we can create the right conditions. As long as we can conserve wildlife corridors that connect their habitats, cheetahs should be able to maintain gene flow between groups and recolonise new areas. Growing human populations will not make any of this any easier. But if people can be persuaded to find a little room in their worlds and in their hearts for these shy, fragile cats, there’s a chance to prevent them from sprinting further along the path to extinction.

Featured image © Michele Lowe