BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

Adaptations

You’ve probably never heard of it, but this pterosaur deserves its own fan club.

Mark Witton is a paleobiologist on a mission. He says more people should know about one spectacular flying animal that lived more than 65 million years ago: Arambourgiania philadelphiae.

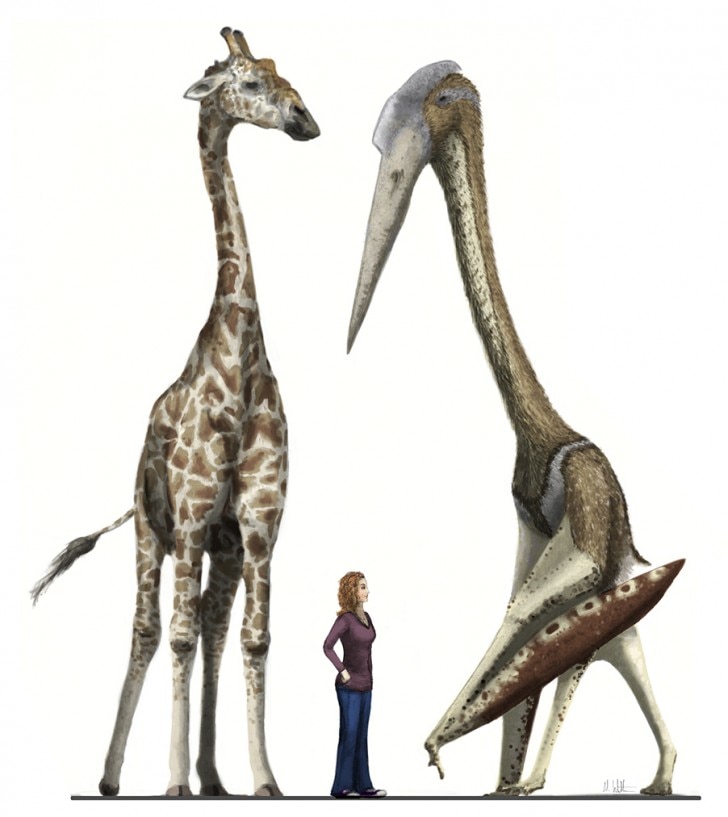

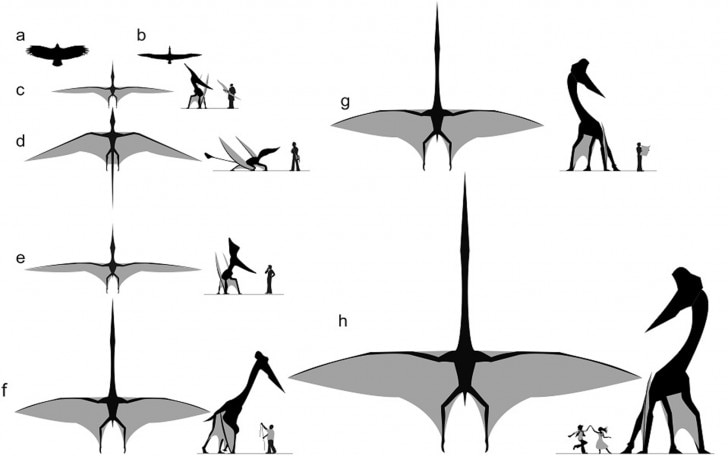

Arambourgiania was a pterosaur – a group of reptiles that includes pterodactyls but which is distinct from dinosaurs. It lived during the Late Cretaceous period, at the same time as Tyrannosaurus rex. Like T. rex, Arambourgiania was big. With an estimated wingspan of around 10m and an unusually long neck, it was one of the largest flying organisms that ever lived - basically the size of a small plane.

“A flying animal with a giraffe-like neck,” says Witton, who is based at the University of Portsmouth. “That’s pretty remarkable.”

Not long ago, Witton wrote a blog post claiming that Arambourgiania deserved a “fan club”. He pointed out that a number other large pterosaurs from the same period, like Quetzalcoatlus northropi, are generally more well known.

It’s possible that Arambourgiania may have been slightly smaller overall, but it is special for another reason. We know that its neck may have been nearly three metres in length.

A flying animal with a giraffe-like neck. That’s pretty remarkable.”

“It’s about double the length of what we’d see in another giant pterosaur,” explains Witton.

It’s hard to say much for certain about this impressive species of pterosaur, but what we know about its neck is based on one of a few surviving fossils – a vertebra, in this case a neck bone. Mysteriously, no-one knows when it was discovered because documentation did not survive with it, but Witton thinks it was likely back in the 1930s or early 1940s. We do know that it was found in Jordan and that the specimen was written about in a 1954 paper by Camille Arambourg, the French palaeontologist from whom the pterosaur gets its name.

The fossil itself is a long, thin tubular bone that indicates the animal’s neck would have been massive and probably quite inflexible.

“Like a pole on the end of a plane,” says Michael Habib, a palaeontologist at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine. “That of course is quite interesting because we’re not particularly accustomed to seeing animals with long, relatively inflexible necks that fly,” he adds.

“It wasn’t super flexible like the neck of a heron or swan.”

For a man-made plane made of metal, having so much mass out in front would be a problem, but Habib explains that a flying animal can compensate for balance during flight by adjusting its wings and shoulders. This is probably what Arambourgiania and other giant pterosaurs with a similar profile did. Fossil skulls suggest that these creatures often had freakishly large heads, though they would have been lighter than they looked thanks to their thin but rigid bone structure.

Besides the vertebra, we also have some additional fossils that likely came from Arambourgiania, including the end of a wing bone, or phalanx. These help reveal a bit more about what this ancient flier looked like.

Witton notes that far more fossil material survives for species like Quetzalcoatlus northropi, which helps to explain why that species has been more widely written about in the press and discussed in museum exhibitions. But new material does turn up all the time, leaving open the possibility that we may soon know much more about Arambourgiania than we do today. For example, in an intriguing development last year that is yet to be peer-reviewed, researchers at the University of Michigan found several new fossils that they say belong to the pterosaur.

More material means paleobiologists are better able to infer how these giants may have actually lived – including how they moved and flew.

Habib says that there are certain things we can rule out about a pterosaur like Arambourgiania, just because of its massive size. It wouldn’t have been a creature that constantly flapped to stay aloft, for example, because this would have required too much energy. It also wouldn’t have been highly manoeuvrable – especially with that pole-like neck. However, Arambourgiania was likely able to soar for long periods and may even have had a flight range so big that it could essentially travel the world. One bit of evidence that hints at this is that we continue to find giant pterosaur fossils, of various species, in many different regions – from Eastern Europe to North America, the Middle East and Asia. “[If they had a global range] you should tend to find them all over the place – and we do, overall,” says Habib.

Pterosaurs are much more than just pterodactyls, then. And this fact is partly why Witton wants to celebrate Arambourgiania. Like T. rex or woolly mammoths, it’s a species that members of the public should know about, besides just academic researchers, he says. After all, it too is part of the long and varied history of our planet.

Plus, there is significant street cred up for grabs for any new fans of Arambourgiania, he points out. “If you’re in the Arambourgiania fan club, you could genuinely say you liked giant pterosaurs before they were cool,” he jokes. “You’re a more hard-core pterosaur fan.”

So go on, be like Arambourgiania. Stick your neck out.

Featured image © Mark Witton