BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

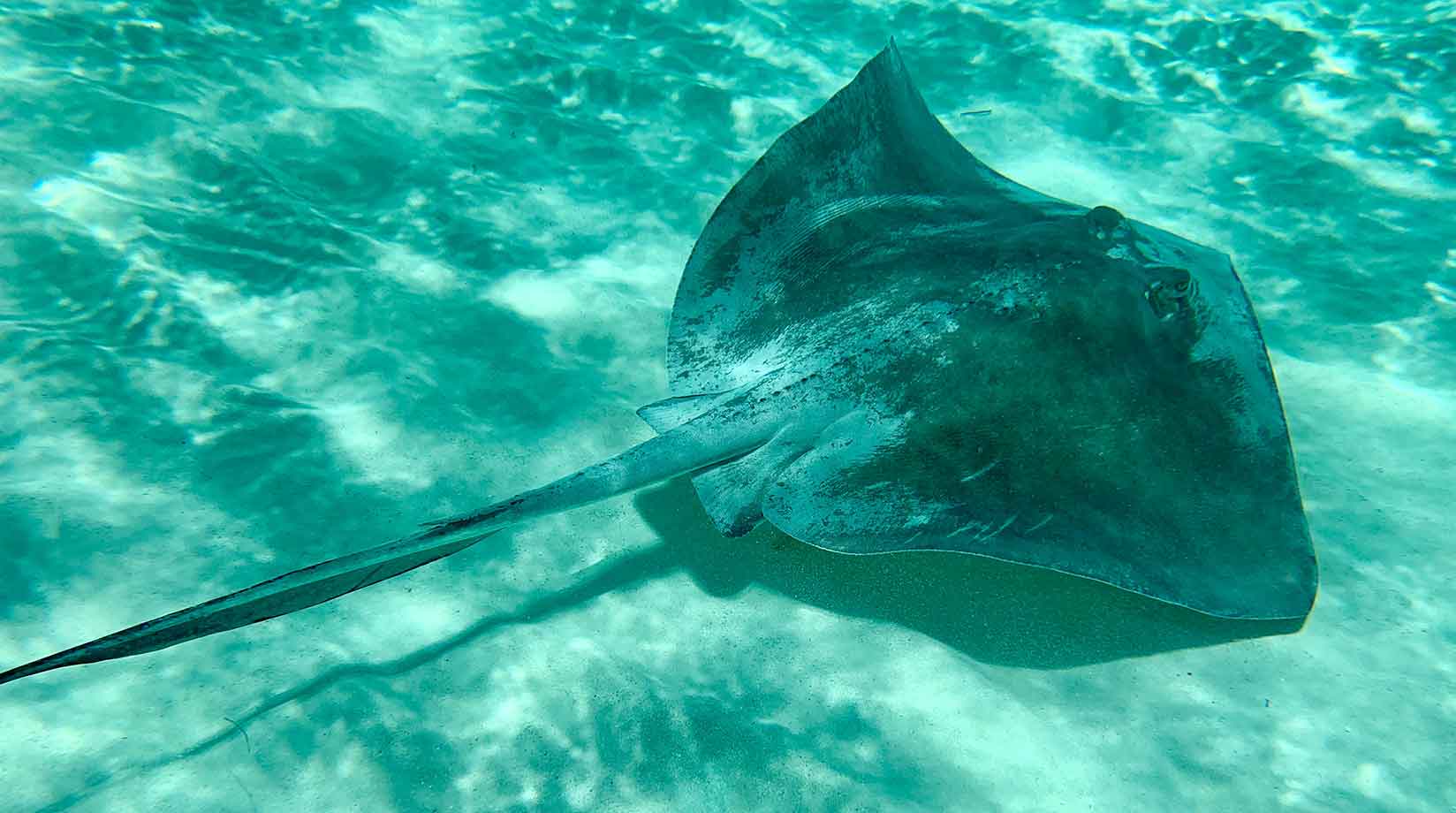

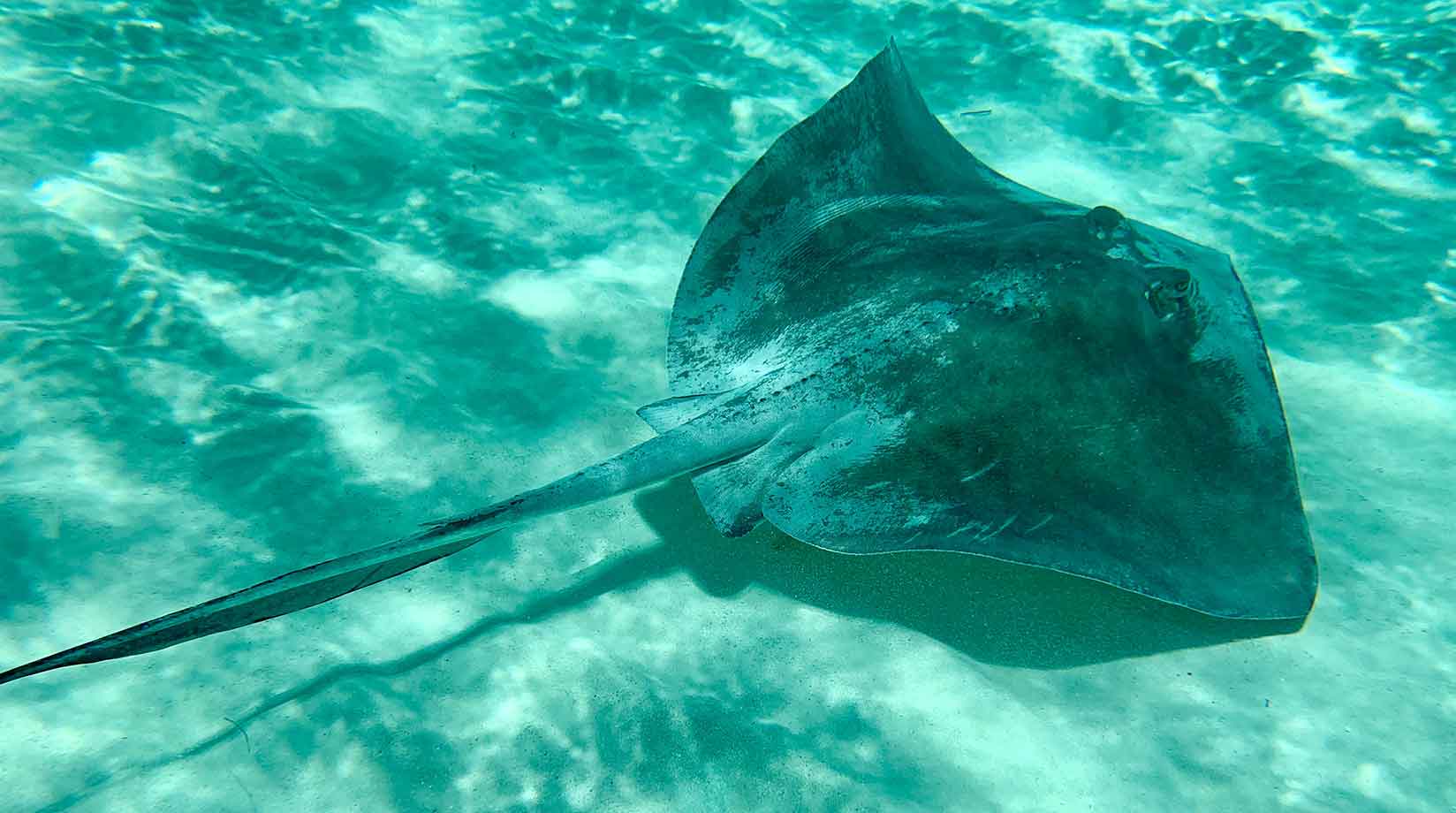

Stingrays are flat, disk-shaped fish with venomous barbed tails. They can typically be found gliding along the floor of shallow, coastal waters in temperate and tropical seas.

Stingray’s unique flattened bodies have fascinated scientists for decades. They are members of a group of fish called batoids that also includes electric rays and manta rays. They are closely related to sharks and have skeletons made of cartilage, not bones (the same material in the bridge of your nose!). Found in both saltwater and freshwater habitats, stingrays are highly adaptable but increasingly at risk due to overfishing and habitat destruction. While their venomous, barbed tail has given these flattened fish a deadly reputation, scientists argue it’s not deserved.

Rays are cartilaginous fish that inhabit the oceans and freshwater rivers of many tropical and temperate parts of the world. Their iconic body shape makes them hard to miss: most rays look like thick, flexible kites flapping elegantly through the water.

Stingrays are categorised as Chondrichthyan, together with sharks, skates, and other types of rays.1 Within this class, skates and rays are divided from sharks into the order Batoidea. There are over 600 different species of rays, including electric rays, eagle rays, manta rays, and stingrays.2 Stingrays are split into 29 groups made up of more than 220 different species.3

The difference between stingrays and other rays can be found within their name. At the end of a stingray’s long tail is a venomous, barbed “stinger”. Another difference is that stingray’s body shapes are flatter and rounder. They are also found in different habitats, using different strategies to find food.

“Stingrays have essentially got that round disc body without a separated a distinct head, you can't really tell the difference between the fins and the head,” says ray researcher William White, from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Australia. “While eagle rays, manta rays, devil rays all have a distinct, raised head.”

“One of the biggest issues with stingrays is that we still know so little of most of the species,” says White. “We're still describing new species regularly.”

Stingrays are fish, not mammals. Mammals are warm-blooded animals that give birth to live young and breathe air with their lungs. Some mammals do live in the ocean (whales, dolphins, and sea lions are mammals), but they do not breathe underwater.

Stingrays do give live birth, but they are cold-blooded and breathe underwater using their gills. Genetically, stingrays are closely related to other fish, which is a key indicator that they belong to the same group.

Stingrays do have skeletons, but they are not made of bone. Like other rays, skates and sharks, stingray skeletons are made of cartilage. Cartilage is the same material in our nose and ears. Scientists think it allows stingray skeletons to be lighter and more flexible while staying strong.4 Notice how if you press against your nose, it can bend easily – but will return to its original shape - as long as it’s not broken!

Yes, stingrays are related to sharks. Stingrays and sharks are in the class Chondrichthyan and the subclass Elasmobranchs. (5) They are similar because they have skeletons made of cartilage and five to seven gill slits. In fact, some people describe stingrays as sharks that have been flattened by a steamroller.

The last common ancestor between sharks and rays has been traced back to around 450 million years ago.6 Unlike bony fish, cartilaginous fish don’t leave behind much fossilised material because their soft tissues and cartilage skeleton degrade more easily than bone. The few fossil records of ancient cartilaginous fish that have survived suggest that the first stingrays evolved during the Late Jurassic period, which is about 150 million years ago. By the Cretaceous period (around 100 million years ago) stingrays had diversified into all of the types of stingrays we know today.7

Stingrays and manta rays both belong to the order Batoidea, so they are closely related.8 There are, however, a few key differences that distinguish them.9

The first is their body shape.10 Stingrays are generally round and flat, while manta rays are larger and more “kite-shaped. Manta rays have triangular pectoral fins, a bit like wings, and forward-facing fleshy appendages around their mouths.

Another difference is their diet and habitat: stingrays are bottom dwellers that search for prey on the sea floor. Mantas are pelagic – they cruise through the open ocean and use their huge mouths to filter and funnel plankton into their digestive system.

Finally, manta rays do not have a stinger on their tail. Stingrays use their venomous tails to defend themselves, but mantas have a different strategy (although researchers believe their long, slim tails are kind of like antennae to sense any approaching danger).11 When they are young, manta rays group up or use their fast and agile swimming to avoid threats. Once they reach adulthood, they are often too large for most predators to attack.

Most stingrays can be found in the coastal waters of tropical and subtropical seas.12Their preferred habitats are sandy or muddy flats, seagrass beds, mangrove forests or coral reefs.

Certain species live in habitats outside their usual range. For example: the Niger stingray lives in freshwater, the deepwater stingray at depths of 275 to 680 metres and the pelagic stingray lives in the open ocean.13

Many stingrays are known to migrate when waters get cold, seeking out warmer, more comfortable temperatures elsewhere. Atlantic stingrays, for instance, live around the US Eastern coast during spring and summer and then migrate further south, all the way down to Mexico, when winter rolls around.14

Stingrays can get big. The largest saltwater stingray is the smalleye stingray.15 It gets its name because its pea-sized eyes are so small compared to its gargantuan wingspan. It reaches over 2.2 metres in width and 3 metres in length. That’s about the size of a king-sized bed.

In 2022, fishermen in the Mekong River of Cambodia reeled in a huge female freshwater stingray measuring more than 4 meters in length and weighing about 300 kilograms, making it the heaviest freshwater fish ever caught.16

While the skin of stingrays may seem smooth to the touch, that’s not exactly the case.

Stingrays have skin similar to sharks. It is covered in thousands of rough, small scales called dermal denticles.17 The scales cover the entire body, from the head down, pointing towards the tail. If you were to stroke a stingray tail from head to tail, it would feel smooth to the touch. But they’re as rough as sandpaper if rubbed the wrong way round.

From above, it might look like stingrays don’t have a mouth.18 That’s because it’s located on its belly facing straight down. Inside that mouth is a set of powerful teeth.

Stingrays' teeth are modified scales: they have two edges, one with ridges (for grip) and one that’s smooth (for crushing).19 These teeth are tightly arranged, forming intermeshed flat plates. They work like a mortar and pestle, crushing the hard shells of molluscs and crustaceans that make up their diet.20

As with sharks, stingrays regularly shed their teeth and grow them back.

During mating season, male stingrays grow sharper teeth that they use to hold onto their stingray partners during mating.21

Stingrays are carnivorous, meaning they eat other animals. They are voracious predators, employing a variety of feeding strategies to munch on their preferred prey. To find food, stingrays use their ampullae of Lorenzini: a specialised sensory organ around their mouths which can detect the electrical signals given off by prey (Sharks have these too!).

“They will ruffle through along the bottom and just use their sensory pores to sort of detect movement,” says ray researcher William White, from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Australia.

After they’ve sensed their prey, they position themselves above them and use their jaw and fins to suck it into their mouths.22 Once captured, they crush them between their plate-like teeth.

“Sometimes in shallow water you get this perfectly stingray-shaped pit in the sand,” says White. Stingrays bring in water through the respiratory openings on the tops of their head, suck water in through that, and then expel it out the mouth. “That kind of pushes sand out the way to get to the animals under the sand,” says White.

Their preferred snack? Clams, oysters, and mussels, as well as crabs and shrimps, marine worms, isopods, and even small fish. Freshwater stingrays also eat insects and their larvae.

Most fish swim by beating their tails, but stingrays propel themselves underwater using their fins. Stingrays have broad pectoral fins that run the full length of their body. They can use these fins in two ways: some undulate their bodies in a wave-like motion, while other species flap their fins up and down (like a bird’s wings) and fly through the water.23

Scientists studying the motion of their bodies predict that stingrays can reach speeds between 1.5 and 2.5 metres per second, reaching up to nine kilometres per hour.24

Stingrays, like mantas and even sharks, have something called countershading colouration.25 This means the top of their body resembles the colour of the ocean floor. This is why many stingrays are grey, green, and beige or have mottled patterns. The bottom of their body matches the colour of the ocean as seen from below, so features lighter shades like white, light grey, resembling the colour of light filtering through seawater. This makes rays harder to spot by prey on the bottom and predators from above.26

Stingrays have a wide variety of predators, including orcas, seals, and larger fish. But their primary predator is the great hammerhead shark.

Hammerhead sharks use sight, smell and even electrical signals (detected by specialized organs called ampullae of Lorenzini) to find stingrays hiding under the sand. Once they’re on top of their prey, they can use their unique head shape to pin the stingray down before biting its large fins.27

Scientists in Australia have also noticed that hammerhead sharks spend much of their time in the shallows of the Great Barrier Reef rather than the deep because that’s where stingrays like to hang out too.28 Stingrays are common prey; scientists have often found their stingers trapped in the digestive tracts of hammerhead sharks.

Like sharks, stingrays lack organs designed for vocalisation. Yet, researchers are starting to realise that some stingrays do make some sound.

The mangrove whipray and cowtail stingray from the Indo-Pacific have been recorded making clicking sounds.29 The first time scientists observed this behaviour, the stingray clicks were so startling, coming from the ray, that the researchers dropped their cameras in shock. Stingrays are thought to produce clicking sounds through their spiracles, two breathing holes on top of their heads that send water through their gills. Stingrays might be clicking their spiracles the same way humans snap their fingers or click our tongues. Similar clicks have been recorded in other types of rays — a blonde ray off the coast of Corsica in the Mediterranean, and an electric ray species, and a species of skate in Indonesia and Australia.30 Researchers don’t yet know why stingrays might be making these sounds.

Stingrays are a subgroup of rays known for their venomous barbs on their tail. Depending on the species, stingray tails have one, two, or three barbs covered in skin, mucus, and prickly spines. The fish flick their tail at potential predators when they feel threatened. The barbs cause a blade-like cut in their victim and inject venom.

Most venomous animals (like snakes) store their venom in specialized glands. Instead, Stingray venom is found in the skin and mucus surrounding the barbs. Scientific studies indicate that age and sex may affect venom composition: young stingrays pack painful punches, but adult rays have a more potent venom that can cause cell death.31

Stingray barbs are dangerous, but they didn’t evolve to hurt humans — they evolved as a mechanism of defence against predators like sharks, seals, and other large fish. Stingrays have no reason to be aggressive against humans unless they feel threatened or provoked. That’s why almost all stingray injuries are found on the feet and legs, usually after somebody accidentally steps on a stingray.32

Getting whipped with a stingray's tail can be very painful, as the barb cuts skin and releases venom. However, the most dangerous injury is the puncture wound that can cause bleeding and infection.33

In 2006, television personality Steve Irwin was fatally stung by a stingray because the fish accidentally penetrated his chest and pierced his heart. Stingray experts note this was an extremely unusual incident, but its notoriety means that stingrays are misunderstood as being much more dangerous than they actually are.34 Fatal stings are extremely rare.

Stingrays give birth to live young through a process called ovoviviparity – a process that includes both the egg and the live birth, both ovo, egg, and vivi, live.

Unlike mammals, which use a placenta to nourish their embryos, stingray embryos feed on the yolk within their eggs while they’re inside the mother’s womb. The eggs hatch inside the mother’s body, and once the young are fully developed, she gives birth to them. In most species, once the babies are born, they’re fully ready to go out in the world on their own.35

You think you’ve seen a stingray’s egg on the beach before? That was probably a skate’s egg instead.36 Skates do not produce live young, but instead they lay eggs in intricate, resistant, leathery patches often dubbed mermaid purses, like the eggs of sharks.

While research is ongoing, recent evidence suggests stingrays can get pregnant without mating with a male. Charlotte, a small stingray held in an aquarium in North Carolina, was pregnant with four pups in early 2024 despite not having shared a tank with a male ray for eight years.37

This behaviour is rare, but it’s not unheard of in animals like rays, skates, and sharks. It’s a process called parthenogenesis, a form of asexual reproduction where the female’s egg isn’t fertilised by sperm but rather by a smaller cell inside the female’s body with most parts of its DNA.

Like many ocean-dwelling creatures, stingray populations are increasingly at risk. Rays are fished purposefully by some communities around the world for their meat and fins, or for the ray leather market.38 Commercial-grade overfishing is also causing rays to become unintentional bycatch in nets meant for other fish.

Water pollution also likely plays a part in stingray vulnerability. In 2016, more than 70 giant freshwater stingrays were found dead in Thailand's Mae Klong River, possibly because of a spill from an ethanol plant or cyanide used to target other fish, which could have poisoned the rays.39

Data about the conservation status of stingrays isn’t always up to date, as the species are under-researched. But at least 40 species of stingrays are currently threatened with extinction. A global assessment of almost 1,200 sharks and rays in 2021 found that 32% of the total group was at risk of extinction. In 2023, at COP28 in Dubai, a stingray called the Java stingaree, of which experts only had one specimen from 1862, was officially declared extinct.40

“A lot of the risks are starting to come to light now, but rays have been very, very late to the mix. It's been one of the groups that's been really left behind,” says ray researcher William White, from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Australia. “We’ve been so focused on charismatic fauna, like sharks, and rays have been invisible so far.”

Featured image © Sense Atelier Unsplash

Fun fact image © Galaxim | Unsplash

Interview:

Ray researcher William White, from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Australia

Fact File:

Stingrays are flat, disk-shaped fish with venomous barbed tails. They can typically be found gliding along the floor of shallow, coastal waters in temperate and tropical seas.

Pups

Fever, School

Carnivorous; clams, oysters, and mussels, crabs and shrimps, marine worms, isopods, and small fish. Freshwater stingrays also eat insects and their larvae

Primarily hammerhead sharks (and other shark species), seals, and other large fish

15-25 years

Between 30 centimetres to 4 meters long (that’s twice the length of a king-sized bed!)

From one kilogram to 300 kilograms

Pacific Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean

Unknown

The venomous barbs on stingray tails are to protect them from predators, not to hunt for food.

Stingray’s unique flattened bodies have fascinated scientists for decades. They are members of a group of fish called batoids that also includes electric rays and manta rays. They are closely related to sharks and have skeletons made of cartilage, not bones (the same material in the bridge of your nose!). Found in both saltwater and freshwater habitats, stingrays are highly adaptable but increasingly at risk due to overfishing and habitat destruction. While their venomous, barbed tail has given these flattened fish a deadly reputation, scientists argue it’s not deserved.

Rays are cartilaginous fish that inhabit the oceans and freshwater rivers of many tropical and temperate parts of the world. Their iconic body shape makes them hard to miss: most rays look like thick, flexible kites flapping elegantly through the water.

Stingrays are categorised as Chondrichthyan, together with sharks, skates, and other types of rays.1 Within this class, skates and rays are divided from sharks into the order Batoidea. There are over 600 different species of rays, including electric rays, eagle rays, manta rays, and stingrays.2 Stingrays are split into 29 groups made up of more than 220 different species.3

The difference between stingrays and other rays can be found within their name. At the end of a stingray’s long tail is a venomous, barbed “stinger”. Another difference is that stingray’s body shapes are flatter and rounder. They are also found in different habitats, using different strategies to find food.

“Stingrays have essentially got that round disc body without a separated a distinct head, you can't really tell the difference between the fins and the head,” says ray researcher William White, from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Australia. “While eagle rays, manta rays, devil rays all have a distinct, raised head.”

“One of the biggest issues with stingrays is that we still know so little of most of the species,” says White. “We're still describing new species regularly.”

Stingrays are fish, not mammals. Mammals are warm-blooded animals that give birth to live young and breathe air with their lungs. Some mammals do live in the ocean (whales, dolphins, and sea lions are mammals), but they do not breathe underwater.

Stingrays do give live birth, but they are cold-blooded and breathe underwater using their gills. Genetically, stingrays are closely related to other fish, which is a key indicator that they belong to the same group.

Stingrays do have skeletons, but they are not made of bone. Like other rays, skates and sharks, stingray skeletons are made of cartilage. Cartilage is the same material in our nose and ears. Scientists think it allows stingray skeletons to be lighter and more flexible while staying strong.4 Notice how if you press against your nose, it can bend easily – but will return to its original shape - as long as it’s not broken!

Yes, stingrays are related to sharks. Stingrays and sharks are in the class Chondrichthyan and the subclass Elasmobranchs. (5) They are similar because they have skeletons made of cartilage and five to seven gill slits. In fact, some people describe stingrays as sharks that have been flattened by a steamroller.

The last common ancestor between sharks and rays has been traced back to around 450 million years ago.6 Unlike bony fish, cartilaginous fish don’t leave behind much fossilised material because their soft tissues and cartilage skeleton degrade more easily than bone. The few fossil records of ancient cartilaginous fish that have survived suggest that the first stingrays evolved during the Late Jurassic period, which is about 150 million years ago. By the Cretaceous period (around 100 million years ago) stingrays had diversified into all of the types of stingrays we know today.7

Stingrays and manta rays both belong to the order Batoidea, so they are closely related.8 There are, however, a few key differences that distinguish them.9

The first is their body shape.10 Stingrays are generally round and flat, while manta rays are larger and more “kite-shaped. Manta rays have triangular pectoral fins, a bit like wings, and forward-facing fleshy appendages around their mouths.

Another difference is their diet and habitat: stingrays are bottom dwellers that search for prey on the sea floor. Mantas are pelagic – they cruise through the open ocean and use their huge mouths to filter and funnel plankton into their digestive system.

Finally, manta rays do not have a stinger on their tail. Stingrays use their venomous tails to defend themselves, but mantas have a different strategy (although researchers believe their long, slim tails are kind of like antennae to sense any approaching danger).11 When they are young, manta rays group up or use their fast and agile swimming to avoid threats. Once they reach adulthood, they are often too large for most predators to attack.

Most stingrays can be found in the coastal waters of tropical and subtropical seas.12Their preferred habitats are sandy or muddy flats, seagrass beds, mangrove forests or coral reefs.

Certain species live in habitats outside their usual range. For example: the Niger stingray lives in freshwater, the deepwater stingray at depths of 275 to 680 metres and the pelagic stingray lives in the open ocean.13

Many stingrays are known to migrate when waters get cold, seeking out warmer, more comfortable temperatures elsewhere. Atlantic stingrays, for instance, live around the US Eastern coast during spring and summer and then migrate further south, all the way down to Mexico, when winter rolls around.14

Stingrays can get big. The largest saltwater stingray is the smalleye stingray.15 It gets its name because its pea-sized eyes are so small compared to its gargantuan wingspan. It reaches over 2.2 metres in width and 3 metres in length. That’s about the size of a king-sized bed.

In 2022, fishermen in the Mekong River of Cambodia reeled in a huge female freshwater stingray measuring more than 4 meters in length and weighing about 300 kilograms, making it the heaviest freshwater fish ever caught.16

While the skin of stingrays may seem smooth to the touch, that’s not exactly the case.

Stingrays have skin similar to sharks. It is covered in thousands of rough, small scales called dermal denticles.17 The scales cover the entire body, from the head down, pointing towards the tail. If you were to stroke a stingray tail from head to tail, it would feel smooth to the touch. But they’re as rough as sandpaper if rubbed the wrong way round.

From above, it might look like stingrays don’t have a mouth.18 That’s because it’s located on its belly facing straight down. Inside that mouth is a set of powerful teeth.

Stingrays' teeth are modified scales: they have two edges, one with ridges (for grip) and one that’s smooth (for crushing).19 These teeth are tightly arranged, forming intermeshed flat plates. They work like a mortar and pestle, crushing the hard shells of molluscs and crustaceans that make up their diet.20

As with sharks, stingrays regularly shed their teeth and grow them back.

During mating season, male stingrays grow sharper teeth that they use to hold onto their stingray partners during mating.21

Stingrays are carnivorous, meaning they eat other animals. They are voracious predators, employing a variety of feeding strategies to munch on their preferred prey. To find food, stingrays use their ampullae of Lorenzini: a specialised sensory organ around their mouths which can detect the electrical signals given off by prey (Sharks have these too!).

“They will ruffle through along the bottom and just use their sensory pores to sort of detect movement,” says ray researcher William White, from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Australia.

After they’ve sensed their prey, they position themselves above them and use their jaw and fins to suck it into their mouths.22 Once captured, they crush them between their plate-like teeth.

“Sometimes in shallow water you get this perfectly stingray-shaped pit in the sand,” says White. Stingrays bring in water through the respiratory openings on the tops of their head, suck water in through that, and then expel it out the mouth. “That kind of pushes sand out the way to get to the animals under the sand,” says White.

Their preferred snack? Clams, oysters, and mussels, as well as crabs and shrimps, marine worms, isopods, and even small fish. Freshwater stingrays also eat insects and their larvae.

Most fish swim by beating their tails, but stingrays propel themselves underwater using their fins. Stingrays have broad pectoral fins that run the full length of their body. They can use these fins in two ways: some undulate their bodies in a wave-like motion, while other species flap their fins up and down (like a bird’s wings) and fly through the water.23

Scientists studying the motion of their bodies predict that stingrays can reach speeds between 1.5 and 2.5 metres per second, reaching up to nine kilometres per hour.24

Stingrays, like mantas and even sharks, have something called countershading colouration.25 This means the top of their body resembles the colour of the ocean floor. This is why many stingrays are grey, green, and beige or have mottled patterns. The bottom of their body matches the colour of the ocean as seen from below, so features lighter shades like white, light grey, resembling the colour of light filtering through seawater. This makes rays harder to spot by prey on the bottom and predators from above.26

Stingrays have a wide variety of predators, including orcas, seals, and larger fish. But their primary predator is the great hammerhead shark.

Hammerhead sharks use sight, smell and even electrical signals (detected by specialized organs called ampullae of Lorenzini) to find stingrays hiding under the sand. Once they’re on top of their prey, they can use their unique head shape to pin the stingray down before biting its large fins.27

Scientists in Australia have also noticed that hammerhead sharks spend much of their time in the shallows of the Great Barrier Reef rather than the deep because that’s where stingrays like to hang out too.28 Stingrays are common prey; scientists have often found their stingers trapped in the digestive tracts of hammerhead sharks.

Like sharks, stingrays lack organs designed for vocalisation. Yet, researchers are starting to realise that some stingrays do make some sound.

The mangrove whipray and cowtail stingray from the Indo-Pacific have been recorded making clicking sounds.29 The first time scientists observed this behaviour, the stingray clicks were so startling, coming from the ray, that the researchers dropped their cameras in shock. Stingrays are thought to produce clicking sounds through their spiracles, two breathing holes on top of their heads that send water through their gills. Stingrays might be clicking their spiracles the same way humans snap their fingers or click our tongues. Similar clicks have been recorded in other types of rays — a blonde ray off the coast of Corsica in the Mediterranean, and an electric ray species, and a species of skate in Indonesia and Australia.30 Researchers don’t yet know why stingrays might be making these sounds.

Stingrays are a subgroup of rays known for their venomous barbs on their tail. Depending on the species, stingray tails have one, two, or three barbs covered in skin, mucus, and prickly spines. The fish flick their tail at potential predators when they feel threatened. The barbs cause a blade-like cut in their victim and inject venom.

Most venomous animals (like snakes) store their venom in specialized glands. Instead, Stingray venom is found in the skin and mucus surrounding the barbs. Scientific studies indicate that age and sex may affect venom composition: young stingrays pack painful punches, but adult rays have a more potent venom that can cause cell death.31

Stingray barbs are dangerous, but they didn’t evolve to hurt humans — they evolved as a mechanism of defence against predators like sharks, seals, and other large fish. Stingrays have no reason to be aggressive against humans unless they feel threatened or provoked. That’s why almost all stingray injuries are found on the feet and legs, usually after somebody accidentally steps on a stingray.32

Getting whipped with a stingray's tail can be very painful, as the barb cuts skin and releases venom. However, the most dangerous injury is the puncture wound that can cause bleeding and infection.33

In 2006, television personality Steve Irwin was fatally stung by a stingray because the fish accidentally penetrated his chest and pierced his heart. Stingray experts note this was an extremely unusual incident, but its notoriety means that stingrays are misunderstood as being much more dangerous than they actually are.34 Fatal stings are extremely rare.

Stingrays give birth to live young through a process called ovoviviparity – a process that includes both the egg and the live birth, both ovo, egg, and vivi, live.

Unlike mammals, which use a placenta to nourish their embryos, stingray embryos feed on the yolk within their eggs while they’re inside the mother’s womb. The eggs hatch inside the mother’s body, and once the young are fully developed, she gives birth to them. In most species, once the babies are born, they’re fully ready to go out in the world on their own.35

You think you’ve seen a stingray’s egg on the beach before? That was probably a skate’s egg instead.36 Skates do not produce live young, but instead they lay eggs in intricate, resistant, leathery patches often dubbed mermaid purses, like the eggs of sharks.

While research is ongoing, recent evidence suggests stingrays can get pregnant without mating with a male. Charlotte, a small stingray held in an aquarium in North Carolina, was pregnant with four pups in early 2024 despite not having shared a tank with a male ray for eight years.37

This behaviour is rare, but it’s not unheard of in animals like rays, skates, and sharks. It’s a process called parthenogenesis, a form of asexual reproduction where the female’s egg isn’t fertilised by sperm but rather by a smaller cell inside the female’s body with most parts of its DNA.

Like many ocean-dwelling creatures, stingray populations are increasingly at risk. Rays are fished purposefully by some communities around the world for their meat and fins, or for the ray leather market.38 Commercial-grade overfishing is also causing rays to become unintentional bycatch in nets meant for other fish.

Water pollution also likely plays a part in stingray vulnerability. In 2016, more than 70 giant freshwater stingrays were found dead in Thailand's Mae Klong River, possibly because of a spill from an ethanol plant or cyanide used to target other fish, which could have poisoned the rays.39

Data about the conservation status of stingrays isn’t always up to date, as the species are under-researched. But at least 40 species of stingrays are currently threatened with extinction. A global assessment of almost 1,200 sharks and rays in 2021 found that 32% of the total group was at risk of extinction. In 2023, at COP28 in Dubai, a stingray called the Java stingaree, of which experts only had one specimen from 1862, was officially declared extinct.40

“A lot of the risks are starting to come to light now, but rays have been very, very late to the mix. It's been one of the groups that's been really left behind,” says ray researcher William White, from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Australia. “We’ve been so focused on charismatic fauna, like sharks, and rays have been invisible so far.”

Featured image © Sense Atelier Unsplash

Fun fact image © Galaxim | Unsplash

Interview:

Ray researcher William White, from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Australia

Fact File:

Pups

Fever, School

Carnivorous; clams, oysters, and mussels, crabs and shrimps, marine worms, isopods, and small fish. Freshwater stingrays also eat insects and their larvae

Primarily hammerhead sharks (and other shark species), seals, and other large fish

15-25 years

Between 30 centimetres to 4 meters long (that’s twice the length of a king-sized bed!)

From one kilogram to 300 kilograms

Pacific Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean

Unknown

The venomous barbs on stingray tails are to protect them from predators, not to hunt for food.