BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

Huntsman spiders are famous the world over for their distinctive appearance: long legs, flat bodies, and hairy backs make them some of the most recognisable and feared spiders. But they’re far less aggressive than their name suggests...

Huntsman spiders, despite their intimidating name, are only aggressive when it comes to ambushing their prey. They are docile spiders, with some species living together in big families, and some pairs spending months ‘dating’ before they’re ready to reproduce. They come in a variety of sizes and colours too.

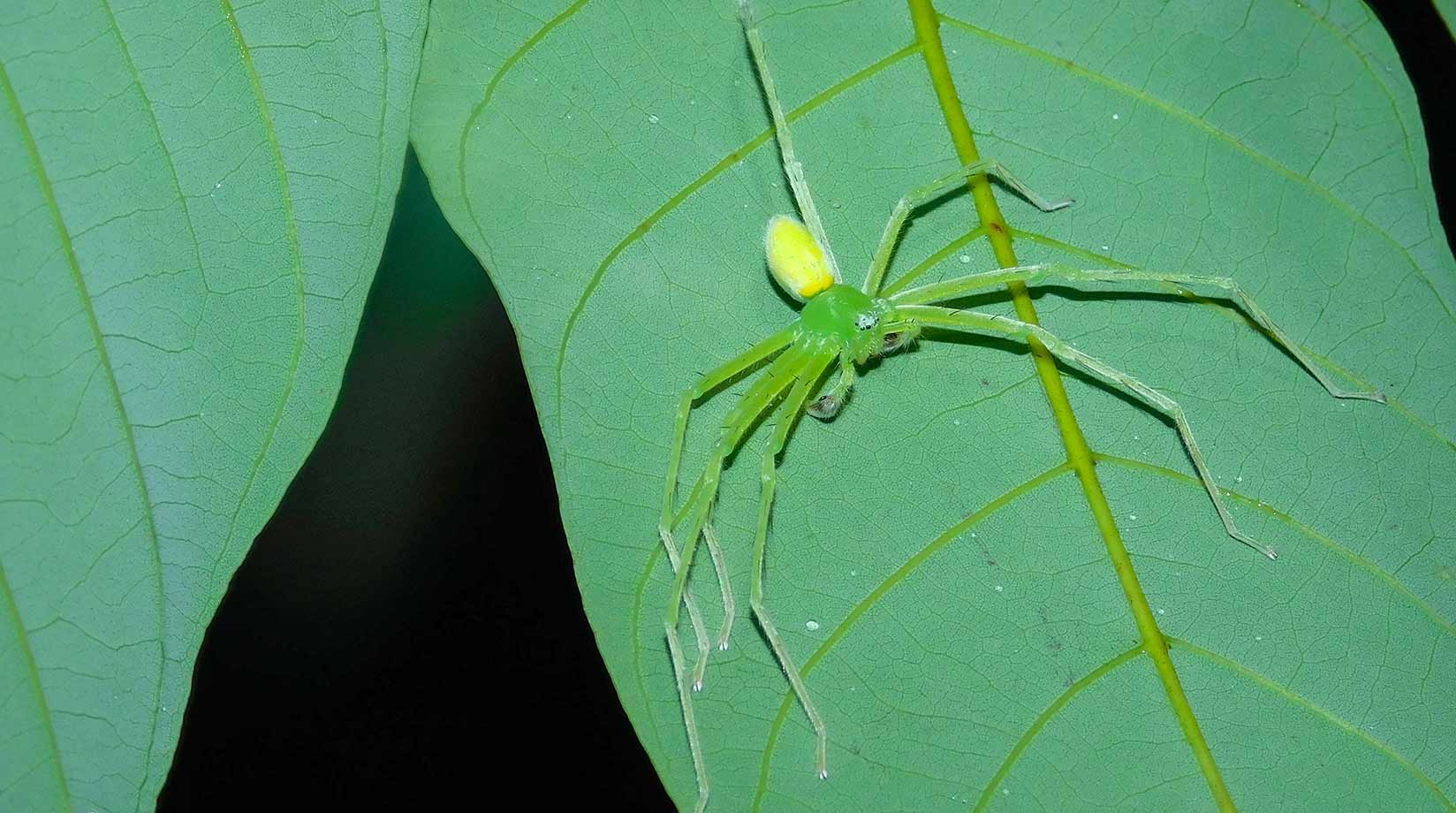

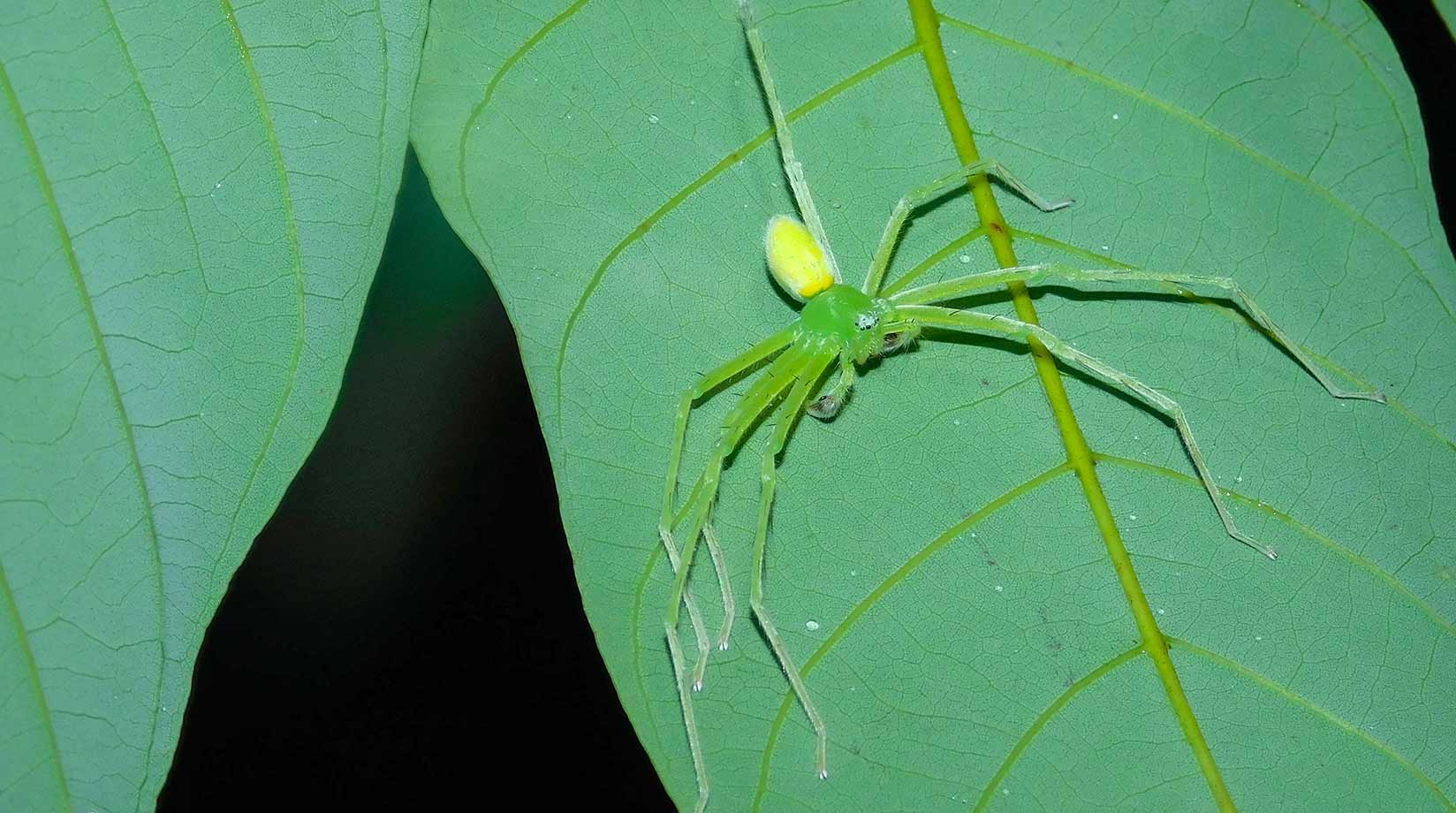

Despite being thought of mostly as large, fuzzy and long-legged, huntsman spiders also come in tiny, colourful varieties.

Huntsman spiders are spiders from the family Sparassidae: they are mostly large, long-legged, long-lived, and hairy.1

They’re sometimes dubbed crab spiders because their legs are folded sideways in a way that allows them to move in a crab-like fashion. Many species are relatively flat, enabling them to squeeze into tight spaces. Arachnologist Linda Rayor from Cornell University in New York is one of the world’s experts on huntsman spider behaviour and she recalls introducing a flat-shaped Australian species to a government official: “He looked at them and said, ‘What is that? A credit card spider?’,” says Rayor.

While huntsman spiders are popular, they’ve not been extensively studied. “Because they're so quick and because they're so large, people are aware of them,” says Rayor. “But remarkably little observation has been done on their behaviour.”

The Sparassidae family is split up into 97 genera of huntsman spiders and more than 1,500 species worldwide.2 “The 10th largest spider family of all of the spider families are huntsman spiders,” says leading huntsman expert Linda Rayor from Cornell University in New York.

While most of them are brown and black and dark colours, they are “incredibly diverse,” says Rayor. “Some of them are just beautiful.” For instance, the Pandercetes gracilis species, also known as the lichen huntsman spider, camouflages almost perfectly on tree bark by looking like, as the name suggests, lichen.3 The Heteropoda davidbowie species – named after the British singer David Bowie – is large and fluffy with white and orange colouring.4 The golden Huntsman from Australia is one of the largest huntsman in the world and it is bright yellow and orange.5

Huntsman spiders live in forests, under loose bark, in holes and depressions of tree trunks, and in nooks and crannies of the woods, but they can also be found inside sheds, homes, and warehouses that are not very busy with human life. In Iran, several species of huntsman spiders live in underground caves.6

Huntsman spiders are nocturnal – they mainly come out at night, slipping out of their homes and nests to hunt, usually for insects and other invertebrates.7

They’re found almost all over the world, typically in warm, tropical, and temperate places. They’re very common and well-known in Australia, for instance, and they’ve even made it all the way to remote Hawaii.

Huntsman spiders, alongside tarantulas, are some of the largest spiders out there. The gargantuan golden huntsman from Australia weighs more than 5.5g. When they’re fully grown, their legs can stretch 15cm from tip to tip, says world huntsman expert Linda Rayor from Cornell University in New York. Female spiders of this size lay egg sacs the size of golf balls.

However, not all huntsman species are large. “I have a very small species right now that, with legs, is about the size of my thumbnail – and that is remarkably tiny,” says Rayor.

Huntsman spiders are part of a category of spiders that – instead of luring their prey into their web and waiting for them to fall into a well-designed trap – sit, wait and hunt their prey down once it gets near. They do not make webs.

With this technique, they pounce on insects, other small spiders, and even lizards and frogs. This is what most huntsman spiders eat, but they can feed on other food sources. Studies show that huntsman spiders living in sand dunes in Namibia like to eat weevils, beetles and moths.8 And in 2019, a video captured a huntsman spider in Tasmania gnawing at a pygmy possum – a small mammal – highlighting the diversity of their diet.9

After capturing their prey, the spiders use their powerful fangs to hold their prey still and immobilise it with venom. Like all spiders, huntsman spiders reduce their food to a pulp before ingesting it. They inject it with enzymes that break down the insides of their prey into a sloppy, slushy mixture and then they slurp it up like soup.10 But they are not solely carnivorous. Some scientists have spotted them feeding on fermenting guava fruit in Trinidad, making huntsman spiders omnivores – critters that eat a bit of everything if they have the chance.11

Huntsman spiders do not build webs. They are part of the group of spiders that get their food via ambush – not by waiting for it to fall into a silk trap, but by hunting it down. They ambush their prey, relying on their speed and agility rather than silk traps to secure their meals.

Like all spiders, though, huntsman spiders still produce silk. They use their silk to make their homes waterproof and compact and to cover their egg sacs in a nice, cosy cocoon.

Some huntsman spiders also use silk once they’ve captured prey. While they do not wrap their prey in silk like some other spider species do, the huntsman spiders dance around their catch of the day, laying down strands of silk on the ground in the process. The reason for this 'victory dance' is still unknown, but it is thought that it may be, in part, to constrain prey.

Huntsman spiders are very fast spiders. “These guys are just incredibly fast animals overall, some of the fastest spiders that have been studied,” says Linda Rayor from Cornell University in New York, one of the world’s experts on huntsman spider behaviour. Holconia hirsuta, a huge hairy huntsman spider from Australia, runs 42 times its body length in a single second. The golden huntsman speeds at 31 body lengths per second.12 Even the slowest species, the badge huntsman, can run 16 body lengths per second.

“Faster than Usain Bolt by a lot,” says Rayor, as Bolt runs just about five times his body lengths per second. Not only are they super speedy, but they are great at running sideways, like crabs, because they have legs that are slightly rotated to the sides rather than positioned directly underneath their bodies. Most huntsman spiders are also skilled at running in a zig-zag pattern, a capability that Rayor says often gives her a headache when she's studying them in the lab.

Huntsman spiders have eight simple eyes, arranged symmetrically in two rows of four. All of these eyes are slick, pearly ‘simple eyes’, meaning they contain just one lens. They are not ‘compound eyes’, like those of bees, which have thousands of lenses.

In 2012, researchers found a huntsman spider species, the Sinopoda scurion, with no eyes at all.13 It lives in caves in Laos and has likely adapted to live in the deep darkness underground by evolving to have no eyes. "We already knew of spiders of this genus from other caves, but they always had eyes," says Peter Jäger in a press release about his discovery.14 "Sinopoda scurion is the first huntsman spider without eyes."

Huntsman spiders aren’t aggressive and they’re “not particularly inclined to bite”, says arachnologist Linda Rayor from Cornell University in New York, one of the world’s experts on huntsman spider behaviour. She’s had them crawling all over her head.

Their main method of defence is running away – because they’re exceptionally fast runners – and hiding, because they’re great at fitting into tiny, tight spaces.

If provoked or threatened, however, they may bite. Their venom is relatively harmless to humans, but can cause some itching, swelling, or temporary pain in the location that’s been bitten.15

A study on huntsman spider bites in Australia found that out of 173 cases recorded over 27 months, 76% of the bites occurred when the spiders were handled or disturbed – either by being picked up or when an object they were on was moved.16

Most spiders are solitary creatures. “Less than 1% of the spiders that are known are social,” says arachnologist Linda Rayor, one of the world’s experts on huntsman spider behaviour. And indeed, almost all huntsman species live alone.

But some have a unique social life. These are the five species that Rayor has spent most of her life studying.

When she started studying the Delena cancerides species from Australia, the best-known social huntsman spiders, Rayor was expecting them to behave like other spiders that show some level of social behaviour. But unlike social spiders, huntsman spiders don’t live in large groups into adulthood.

And unlike sub-social spiders, they don’t just spend a month together in social groups right after hatching. “My guys are staying together for a year,” says Rayor. By the time the spiders leave the nest, they're big, powerful spiders that could easily kill their siblings and their mum. “There could be a lot of conflict, and this isn't what's happening,” says Rayor. “So it was apparent when I first started studying these guys, that they were completely different; they're clearly way more interesting and doing more.”

They solicit food from mum, and they share prey with their siblings. “That means they’re very tolerant,” says Rayor.

While the Delena cancerides is the most famous social huntsman, Rayor has discovered four more species with similar behaviours – three in Australia and one in Madagascar – and has tracked down their lineages.17 She suspects scientists are close to discovering others in Papua New Guinea and Ecuador.

“My anticipation is that you will find social species in other parts of the world,” says Rayor. “There are probably a number of other species that actually show social behaviour, and people just haven't been looking.”

Some huntsman spiders are far more social than most species of arachnids, with social species often travelling in pairs. When Linda Rayor, one of the world’s experts on huntsman spider behaviour, ran a survey on the spiders she was collecting, she noticed about 15% were in pairs – either mothers with offspring or two romantic partners.

One of the reasons huntsman spiders can be found in pairs is because male and female partners spend quite a long time together before mating. Male spiders often wait around for their female partners to mature, sometimes for months. “I found a male with a female who was two months before she made it to sexual maturity,” says Rayor – it's a little bit like these couples are dating before they get married. Then, the mating ritual also is a longer endeavour than with most spiders. (More below!)

In social huntsman spider species, males often guard their female partner for several weeks before mating, waiting for them to become mature enough to reproduce.

Since these species show little variation in size and shape between males and females, conflicts before or during mating are rare. “Huntsman females are terrifically patient with males,” says Linda Rayor, one of the world’s experts on huntsman spider behaviour. There is a lot of tolerance between huntsman spiders.

Once they’re ready to mate, huntsman spiders mate repeatedly over long periods of time. “For eight hours or four hours or two hours – you know, really long, long periods,” says Rayor.

Huntsman spiders from the genus Isopoda engage in a lengthy courtship, which includes caresses and tree drumming.18

In contrast, non-social huntsman spiders like the golden huntsman – the largest huntsman species – can get a little more aggressive and might require a more cautious approach during courtship. But overall, even non-social huntsman spiders “are also fairly tolerant of the males,” says Rayor. “The males are tolerated and can be around the females for months without danger.”19

Aside from having some uniquely social species among the huntsman spiders, another interesting social anecdote about these arachnids is that they are “really good mums,” says Linda Rayor, one of the world’s experts on huntsman spider behaviour. “They're distinctively good mothers.”

How can a spider be a good mum? In the case of the huntsman spiders, mothers guard their egg sacks throughout the three weeks of development, says Rayor. Some species in Australia, even help the spiders hatch out of the sacks, cutting little holes in them for when the spiderlings are ready to come out, says Rayor. Once hatched, most species have spiderlings stay on or around the silky egg sac for about a week, and then they'll disperse out into the wild when they’re ready.

Once the spiderlings disperse, they’re ready for their solitary life and begin their hunt for a mate.

Featured image © Sonika Agarwal | Unsplash

Fun fact image © David Clode | Unsplash

Interviews:

The interview with arachnologist Linda Rayor was conducted over Zoom in November 2024.

Fact File:

1. World Spider Catalog. “Family Sparassidae.” Natural History Museum Bern, accessed January 6, 2025. https://wsc.nmbe.ch/family/90/Sparassidae.Rayor; Linda S. "Huntsman Spiders: Enormous, Fast, and Surprisingly Social." Tarantulas and Identification Guide (TITAG), 2018. Accessed January 6, 2025. http://titag.org/2018/2018papers/rayorhuntsman.pdf.

2. iNaturalist. “Pandercetes gracilis.” Accessed January 6, 2025. https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/368687-Pandercetes-gracilis.

3. iNaturalist. “Heteropoda davidbowie.” Accessed January 6, 2025. https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/542254-Heteropoda-davidbowie.

4. iNaturalist. “Beregama aurea.” Accessed January 6, 2025. https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/368521-Beregama-aurea.

5. Harms, Danilo, and Gonzalo Giribet. "Out of the Blind Spot: The Rediscovery of Sinopoda scurion (Araneae, Sparassidae), the First Troglobitic Huntsman Spider from Laos, with a Redescription of the Species." Subterranean Biology 25 (2018): 51–63. https://subtbiol.pensoft.net/article/20985/.

6. Kona Coast Pest Control. “Cane Spider.” Accessed January 6, 2025. https://konacoastpestcontrol.com/pest-info/spiders/cane-spider/.

7. Henschel, Joh R. "Diet and Foraging Behaviour of Huntsman Spiders in the Namib Dunes (Araneae: Heteropodidae)." Journal of Zoology 234, no. 2 (1994): 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1994.tb06072.x.

8. The Guardian. "Epic Photo: Huntsman Spider Eats Pygmy Possum in Tasmania." Last modified June 18, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jun/18/epic-photo-huntsman….

9. Australian Museum. “Prey Capture and Feeding.” Accessed January 6, 2025. https://australian.museum/learn/animals/spiders/prey-capture-and-feedin….

10. Boos, Hans E. A. "Observation of a Spider of the Sparassidae Family Feeding on Fermenting Guava Fruit in Trinidad." ResearchGate, 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369472334_Observation_of_a_spi….

11. Mather, Rob. "Hidden Housemates: Australia's Huge and Hairy Huntsman Spiders." The Conversation, February 22, 2016. https://theconversation.com/hidden-housemates-australias-huge-and-hairy….

12. Griswold, Charles E., and Peter Jäger. "A New Cave-Dwelling Huntsman Spider, Sinopoda scurion (Araneae: Sparassidae), the First Eyeless Species in the Family." Zootaxa 3415, no. 1 (2012): 81–91. https://mapress.com/zt/article/view/zootaxa.3415.1.3.

13. World Spider Catalog. "Sinopoda scurion." Natural History Museum Bern, accessed January 6, 2025. https://wsc.nmbe.ch/species/35368/Sinopoda_scurion.Phys.org. "World's First Eyeless Huntsman Spider Discovered in Laos." Last modified August 8, 2012. https://phys.org/news/2012-08-world-eyeless-huntsman-spider.html.

14. First Aid Pro Adelaide. "How Dangerous Is a Huntsman Spider Bite?" Accessed January 6, 2025. https://www.firstaidproadelaide.com.au/blog/how-dangerous-is-a-huntsman….

15. Gorneau, J.A. et al. (2022) ‘Huntsman Spider Phylogeny informs evolution of life history, egg sacs, and morphology’, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 174, p. 107530. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2022.107530.

16. Aarhus University. "Social Spiders." SpiderLab, Department of Biology. Accessed January 6, 2025. https://bio.au.dk/en/research/research-areas/genetics-and-evolution/spi….

17. Isbister, G.K. and Hirst, D. (2003) ‘A prospective study of definite bites by spiders of the family Sparassidae (huntsmen spiders) with identification to species level’, Toxicon, 42(2), pp. 163–171. doi:10.1016/s0041-0101(03)00129-6.

18. Australian Museum. "Huntsman Spiders." Accessed January 6, 2025. https://australian.museum/learn/animals/spiders/huntsman-spiders.

19. Huntsman, Golden, and Beregama Aurea. n.d. “Care Guide.” Accessed July 24, 2025. https://shop.minibeastwildlife.com.au/content/Minibeast%20Wildlife%20Ca….

Huntsman spiders are famous the world over for their distinctive appearance: long legs, flat bodies, and hairy backs make them some of the most recognisable and feared spiders. But they’re far less aggressive than their name suggests...

Huntsman spiders, despite their intimidating name, are only aggressive when it comes to ambushing their prey. They are docile spiders, with some species living together in big families, and some pairs spending months ‘dating’ before they’re ready to reproduce. They come in a variety of sizes and colours too.

Spiderlings

Cluster, clutter

Mainly insects, other spiders, small reptiles, amphibians and mammals

Birds, reptiles, mammals and some large insects

An average of 2 to 2.5 years

Large huntsman spiders can reach a leg span of almost 30cm, but on average they’re about the size of a human hand

On average they weigh 1 to 2g, but large ones can be a weigh over 5.5g

Europe, Asia, Africa, North America, South America

n/a

Huntsman spiders are some of the fastest spiders out there - almost 8 times faster than Usain Bolt.

Despite being thought of mostly as large, fuzzy and long-legged, huntsman spiders also come in tiny, colourful varieties.

Huntsman spiders are spiders from the family Sparassidae: they are mostly large, long-legged, long-lived, and hairy.1

They’re sometimes dubbed crab spiders because their legs are folded sideways in a way that allows them to move in a crab-like fashion. Many species are relatively flat, enabling them to squeeze into tight spaces. Arachnologist Linda Rayor from Cornell University in New York is one of the world’s experts on huntsman spider behaviour and she recalls introducing a flat-shaped Australian species to a government official: “He looked at them and said, ‘What is that? A credit card spider?’,” says Rayor.

While huntsman spiders are popular, they’ve not been extensively studied. “Because they're so quick and because they're so large, people are aware of them,” says Rayor. “But remarkably little observation has been done on their behaviour.”

The Sparassidae family is split up into 97 genera of huntsman spiders and more than 1,500 species worldwide.2 “The 10th largest spider family of all of the spider families are huntsman spiders,” says leading huntsman expert Linda Rayor from Cornell University in New York.

While most of them are brown and black and dark colours, they are “incredibly diverse,” says Rayor. “Some of them are just beautiful.” For instance, the Pandercetes gracilis species, also known as the lichen huntsman spider, camouflages almost perfectly on tree bark by looking like, as the name suggests, lichen.3 The Heteropoda davidbowie species – named after the British singer David Bowie – is large and fluffy with white and orange colouring.4 The golden Huntsman from Australia is one of the largest huntsman in the world and it is bright yellow and orange.5

Huntsman spiders live in forests, under loose bark, in holes and depressions of tree trunks, and in nooks and crannies of the woods, but they can also be found inside sheds, homes, and warehouses that are not very busy with human life. In Iran, several species of huntsman spiders live in underground caves.6

Huntsman spiders are nocturnal – they mainly come out at night, slipping out of their homes and nests to hunt, usually for insects and other invertebrates.7

They’re found almost all over the world, typically in warm, tropical, and temperate places. They’re very common and well-known in Australia, for instance, and they’ve even made it all the way to remote Hawaii.

Huntsman spiders, alongside tarantulas, are some of the largest spiders out there. The gargantuan golden huntsman from Australia weighs more than 5.5g. When they’re fully grown, their legs can stretch 15cm from tip to tip, says world huntsman expert Linda Rayor from Cornell University in New York. Female spiders of this size lay egg sacs the size of golf balls.

However, not all huntsman species are large. “I have a very small species right now that, with legs, is about the size of my thumbnail – and that is remarkably tiny,” says Rayor.

Huntsman spiders are part of a category of spiders that – instead of luring their prey into their web and waiting for them to fall into a well-designed trap – sit, wait and hunt their prey down once it gets near. They do not make webs.

With this technique, they pounce on insects, other small spiders, and even lizards and frogs. This is what most huntsman spiders eat, but they can feed on other food sources. Studies show that huntsman spiders living in sand dunes in Namibia like to eat weevils, beetles and moths.8 And in 2019, a video captured a huntsman spider in Tasmania gnawing at a pygmy possum – a small mammal – highlighting the diversity of their diet.9

After capturing their prey, the spiders use their powerful fangs to hold their prey still and immobilise it with venom. Like all spiders, huntsman spiders reduce their food to a pulp before ingesting it. They inject it with enzymes that break down the insides of their prey into a sloppy, slushy mixture and then they slurp it up like soup.10 But they are not solely carnivorous. Some scientists have spotted them feeding on fermenting guava fruit in Trinidad, making huntsman spiders omnivores – critters that eat a bit of everything if they have the chance.11

Huntsman spiders do not build webs. They are part of the group of spiders that get their food via ambush – not by waiting for it to fall into a silk trap, but by hunting it down. They ambush their prey, relying on their speed and agility rather than silk traps to secure their meals.

Like all spiders, though, huntsman spiders still produce silk. They use their silk to make their homes waterproof and compact and to cover their egg sacs in a nice, cosy cocoon.

Some huntsman spiders also use silk once they’ve captured prey. While they do not wrap their prey in silk like some other spider species do, the huntsman spiders dance around their catch of the day, laying down strands of silk on the ground in the process. The reason for this 'victory dance' is still unknown, but it is thought that it may be, in part, to constrain prey.

Huntsman spiders are very fast spiders. “These guys are just incredibly fast animals overall, some of the fastest spiders that have been studied,” says Linda Rayor from Cornell University in New York, one of the world’s experts on huntsman spider behaviour. Holconia hirsuta, a huge hairy huntsman spider from Australia, runs 42 times its body length in a single second. The golden huntsman speeds at 31 body lengths per second.12 Even the slowest species, the badge huntsman, can run 16 body lengths per second.

“Faster than Usain Bolt by a lot,” says Rayor, as Bolt runs just about five times his body lengths per second. Not only are they super speedy, but they are great at running sideways, like crabs, because they have legs that are slightly rotated to the sides rather than positioned directly underneath their bodies. Most huntsman spiders are also skilled at running in a zig-zag pattern, a capability that Rayor says often gives her a headache when she's studying them in the lab.

Huntsman spiders have eight simple eyes, arranged symmetrically in two rows of four. All of these eyes are slick, pearly ‘simple eyes’, meaning they contain just one lens. They are not ‘compound eyes’, like those of bees, which have thousands of lenses.

In 2012, researchers found a huntsman spider species, the Sinopoda scurion, with no eyes at all.13 It lives in caves in Laos and has likely adapted to live in the deep darkness underground by evolving to have no eyes. "We already knew of spiders of this genus from other caves, but they always had eyes," says Peter Jäger in a press release about his discovery.14 "Sinopoda scurion is the first huntsman spider without eyes."

Huntsman spiders aren’t aggressive and they’re “not particularly inclined to bite”, says arachnologist Linda Rayor from Cornell University in New York, one of the world’s experts on huntsman spider behaviour. She’s had them crawling all over her head.

Their main method of defence is running away – because they’re exceptionally fast runners – and hiding, because they’re great at fitting into tiny, tight spaces.

If provoked or threatened, however, they may bite. Their venom is relatively harmless to humans, but can cause some itching, swelling, or temporary pain in the location that’s been bitten.15

A study on huntsman spider bites in Australia found that out of 173 cases recorded over 27 months, 76% of the bites occurred when the spiders were handled or disturbed – either by being picked up or when an object they were on was moved.16

Most spiders are solitary creatures. “Less than 1% of the spiders that are known are social,” says arachnologist Linda Rayor, one of the world’s experts on huntsman spider behaviour. And indeed, almost all huntsman species live alone.

But some have a unique social life. These are the five species that Rayor has spent most of her life studying.

When she started studying the Delena cancerides species from Australia, the best-known social huntsman spiders, Rayor was expecting them to behave like other spiders that show some level of social behaviour. But unlike social spiders, huntsman spiders don’t live in large groups into adulthood.

And unlike sub-social spiders, they don’t just spend a month together in social groups right after hatching. “My guys are staying together for a year,” says Rayor. By the time the spiders leave the nest, they're big, powerful spiders that could easily kill their siblings and their mum. “There could be a lot of conflict, and this isn't what's happening,” says Rayor. “So it was apparent when I first started studying these guys, that they were completely different; they're clearly way more interesting and doing more.”

They solicit food from mum, and they share prey with their siblings. “That means they’re very tolerant,” says Rayor.

While the Delena cancerides is the most famous social huntsman, Rayor has discovered four more species with similar behaviours – three in Australia and one in Madagascar – and has tracked down their lineages.17 She suspects scientists are close to discovering others in Papua New Guinea and Ecuador.

“My anticipation is that you will find social species in other parts of the world,” says Rayor. “There are probably a number of other species that actually show social behaviour, and people just haven't been looking.”

Some huntsman spiders are far more social than most species of arachnids, with social species often travelling in pairs. When Linda Rayor, one of the world’s experts on huntsman spider behaviour, ran a survey on the spiders she was collecting, she noticed about 15% were in pairs – either mothers with offspring or two romantic partners.

One of the reasons huntsman spiders can be found in pairs is because male and female partners spend quite a long time together before mating. Male spiders often wait around for their female partners to mature, sometimes for months. “I found a male with a female who was two months before she made it to sexual maturity,” says Rayor – it's a little bit like these couples are dating before they get married. Then, the mating ritual also is a longer endeavour than with most spiders. (More below!)

In social huntsman spider species, males often guard their female partner for several weeks before mating, waiting for them to become mature enough to reproduce.

Since these species show little variation in size and shape between males and females, conflicts before or during mating are rare. “Huntsman females are terrifically patient with males,” says Linda Rayor, one of the world’s experts on huntsman spider behaviour. There is a lot of tolerance between huntsman spiders.

Once they’re ready to mate, huntsman spiders mate repeatedly over long periods of time. “For eight hours or four hours or two hours – you know, really long, long periods,” says Rayor.

Huntsman spiders from the genus Isopoda engage in a lengthy courtship, which includes caresses and tree drumming.18

In contrast, non-social huntsman spiders like the golden huntsman – the largest huntsman species – can get a little more aggressive and might require a more cautious approach during courtship. But overall, even non-social huntsman spiders “are also fairly tolerant of the males,” says Rayor. “The males are tolerated and can be around the females for months without danger.”19

Aside from having some uniquely social species among the huntsman spiders, another interesting social anecdote about these arachnids is that they are “really good mums,” says Linda Rayor, one of the world’s experts on huntsman spider behaviour. “They're distinctively good mothers.”

How can a spider be a good mum? In the case of the huntsman spiders, mothers guard their egg sacks throughout the three weeks of development, says Rayor. Some species in Australia, even help the spiders hatch out of the sacks, cutting little holes in them for when the spiderlings are ready to come out, says Rayor. Once hatched, most species have spiderlings stay on or around the silky egg sac for about a week, and then they'll disperse out into the wild when they’re ready.

Once the spiderlings disperse, they’re ready for their solitary life and begin their hunt for a mate.

Featured image © Sonika Agarwal | Unsplash

Fun fact image © David Clode | Unsplash

Interviews:

The interview with arachnologist Linda Rayor was conducted over Zoom in November 2024.

Fact File:

1. World Spider Catalog. “Family Sparassidae.” Natural History Museum Bern, accessed January 6, 2025. https://wsc.nmbe.ch/family/90/Sparassidae.Rayor; Linda S. "Huntsman Spiders: Enormous, Fast, and Surprisingly Social." Tarantulas and Identification Guide (TITAG), 2018. Accessed January 6, 2025. http://titag.org/2018/2018papers/rayorhuntsman.pdf.

2. iNaturalist. “Pandercetes gracilis.” Accessed January 6, 2025. https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/368687-Pandercetes-gracilis.

3. iNaturalist. “Heteropoda davidbowie.” Accessed January 6, 2025. https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/542254-Heteropoda-davidbowie.

4. iNaturalist. “Beregama aurea.” Accessed January 6, 2025. https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/368521-Beregama-aurea.

5. Harms, Danilo, and Gonzalo Giribet. "Out of the Blind Spot: The Rediscovery of Sinopoda scurion (Araneae, Sparassidae), the First Troglobitic Huntsman Spider from Laos, with a Redescription of the Species." Subterranean Biology 25 (2018): 51–63. https://subtbiol.pensoft.net/article/20985/.

6. Kona Coast Pest Control. “Cane Spider.” Accessed January 6, 2025. https://konacoastpestcontrol.com/pest-info/spiders/cane-spider/.

7. Henschel, Joh R. "Diet and Foraging Behaviour of Huntsman Spiders in the Namib Dunes (Araneae: Heteropodidae)." Journal of Zoology 234, no. 2 (1994): 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1994.tb06072.x.

8. The Guardian. "Epic Photo: Huntsman Spider Eats Pygmy Possum in Tasmania." Last modified June 18, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jun/18/epic-photo-huntsman….

9. Australian Museum. “Prey Capture and Feeding.” Accessed January 6, 2025. https://australian.museum/learn/animals/spiders/prey-capture-and-feedin….

10. Boos, Hans E. A. "Observation of a Spider of the Sparassidae Family Feeding on Fermenting Guava Fruit in Trinidad." ResearchGate, 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369472334_Observation_of_a_spi….

11. Mather, Rob. "Hidden Housemates: Australia's Huge and Hairy Huntsman Spiders." The Conversation, February 22, 2016. https://theconversation.com/hidden-housemates-australias-huge-and-hairy….

12. Griswold, Charles E., and Peter Jäger. "A New Cave-Dwelling Huntsman Spider, Sinopoda scurion (Araneae: Sparassidae), the First Eyeless Species in the Family." Zootaxa 3415, no. 1 (2012): 81–91. https://mapress.com/zt/article/view/zootaxa.3415.1.3.

13. World Spider Catalog. "Sinopoda scurion." Natural History Museum Bern, accessed January 6, 2025. https://wsc.nmbe.ch/species/35368/Sinopoda_scurion.Phys.org. "World's First Eyeless Huntsman Spider Discovered in Laos." Last modified August 8, 2012. https://phys.org/news/2012-08-world-eyeless-huntsman-spider.html.

14. First Aid Pro Adelaide. "How Dangerous Is a Huntsman Spider Bite?" Accessed January 6, 2025. https://www.firstaidproadelaide.com.au/blog/how-dangerous-is-a-huntsman….

15. Gorneau, J.A. et al. (2022) ‘Huntsman Spider Phylogeny informs evolution of life history, egg sacs, and morphology’, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 174, p. 107530. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2022.107530.

16. Aarhus University. "Social Spiders." SpiderLab, Department of Biology. Accessed January 6, 2025. https://bio.au.dk/en/research/research-areas/genetics-and-evolution/spi….

17. Isbister, G.K. and Hirst, D. (2003) ‘A prospective study of definite bites by spiders of the family Sparassidae (huntsmen spiders) with identification to species level’, Toxicon, 42(2), pp. 163–171. doi:10.1016/s0041-0101(03)00129-6.

18. Australian Museum. "Huntsman Spiders." Accessed January 6, 2025. https://australian.museum/learn/animals/spiders/huntsman-spiders.

19. Huntsman, Golden, and Beregama Aurea. n.d. “Care Guide.” Accessed July 24, 2025. https://shop.minibeastwildlife.com.au/content/Minibeast%20Wildlife%20Ca….

Spiderlings

Cluster, clutter

Mainly insects, other spiders, small reptiles, amphibians and mammals

Birds, reptiles, mammals and some large insects

An average of 2 to 2.5 years

Large huntsman spiders can reach a leg span of almost 30cm, but on average they’re about the size of a human hand

On average they weigh 1 to 2g, but large ones can be a weigh over 5.5g

Europe, Asia, Africa, North America, South America

n/a

Huntsman spiders are some of the fastest spiders out there - almost 8 times faster than Usain Bolt.