BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

Space exploration

Photographing the night sky requires patience and an artistic eye.

Astrophotographer Bray Falls shoots images that are out of this world. We talk to the 24-year-old about resilience, the effect of climate change on his work, his favourite celestial wonders and – most importantly – his first telescope!

My passion came about in a pretty interesting way. I started doing astronomy visually with my first telescope when I was 14. My interest was only in observing space. When you do visual astronomy, you quickly learn that the human eye has severe limitations in the dark. Almost nothing in the night sky has colour when observed with the eye, and many objects appear as faint grey blobs. Cameras allow you to “see” much more detail and colour in the night sky, as well as allowing you to actually share the view with other people, so this route made the most sense to me.

It’s a progression of my love for all things nature. As a young kid I was obsessed with dinosaurs, then geology, then growing plants, and then eventually I discovered there was a whole world above me that wasn’t visible to my eyes. I read a story about how you could see Jupiter’s moons with nothing but a pair of binoculars, and I decided to give it a go. I was amazed to see all four moons of Jupiter in clear view, which had previously been invisible to my eyes. From there it only snowballed.

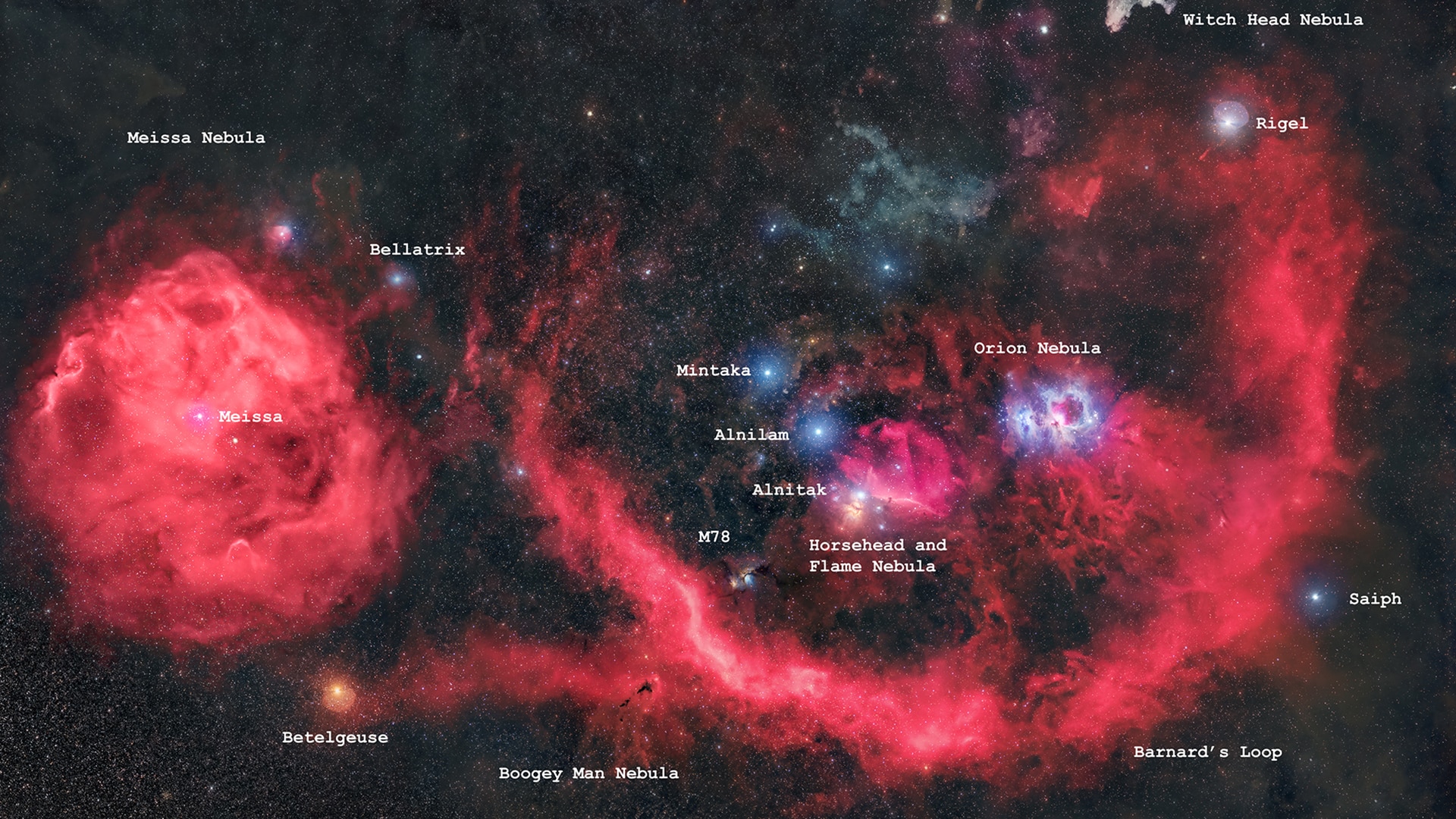

The constellation of Orion is hard to beat. It has one of the most dense collections of nebulae in the sky, and it can be photographed well at almost any level of focal length. It’s home to the great Orion Nebula, Horsehead Nebula, M78, Barnard’s Loop, Witch Head Nebula, and many others. My favorite of these has to be the Horsehead Nebula, which everyone knows from the famous Hubble telescope images.

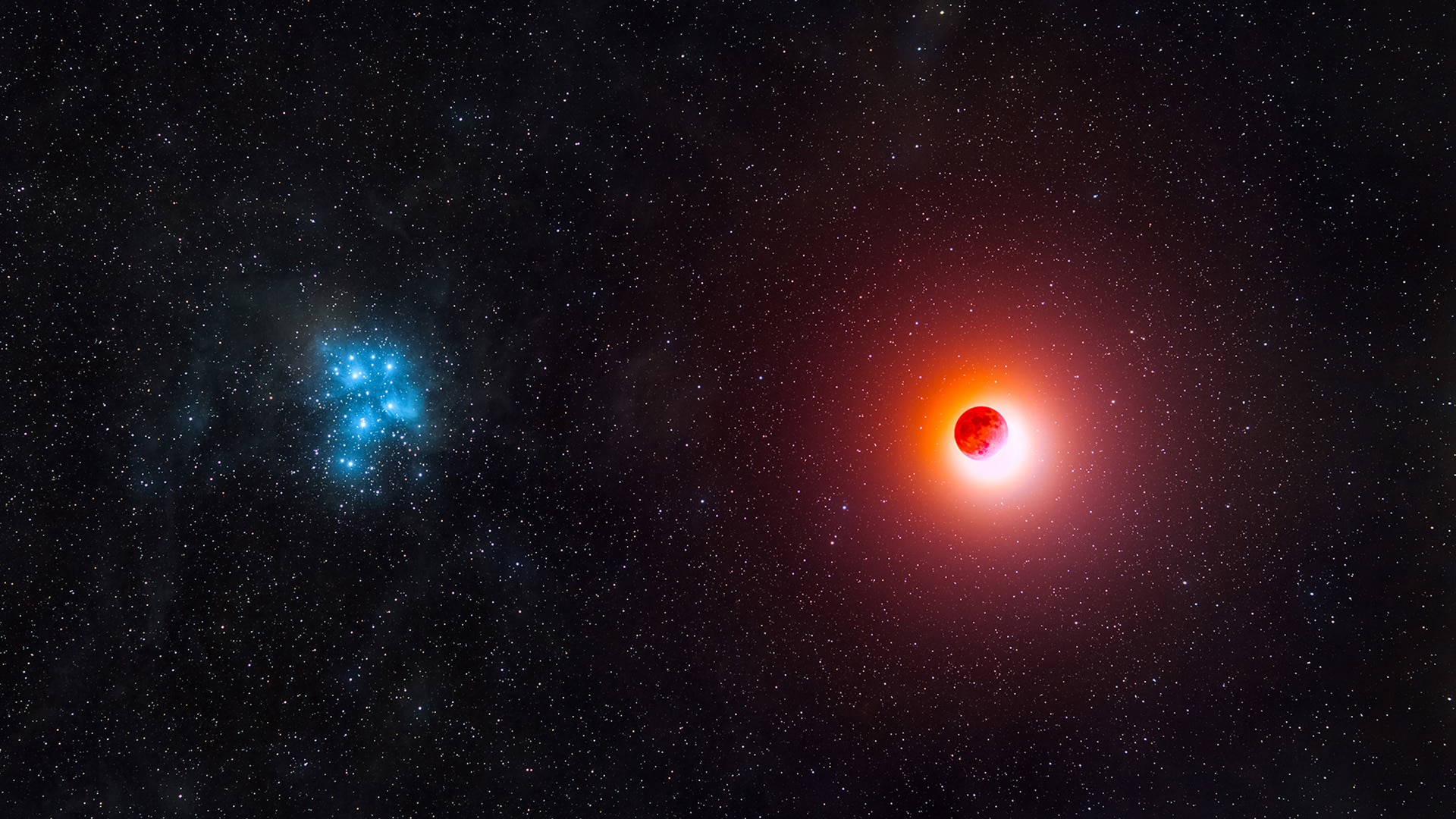

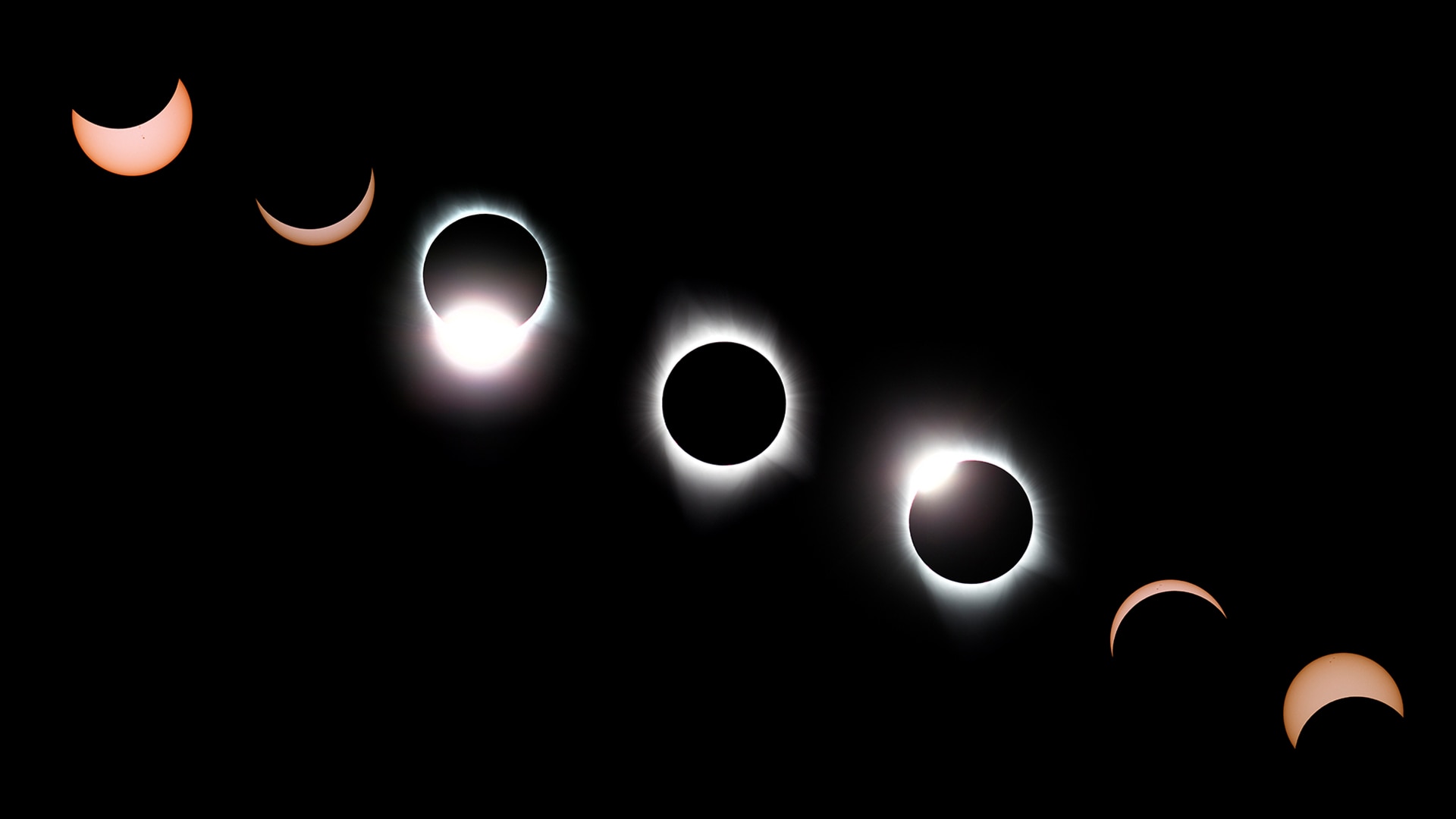

It's tough to be proud of your own photographs sometimes, but for me it would be my photo of the eclipsed moon and the Pleiades star cluster. A photo like that is only possible during a lunar eclipse, because otherwise the moon is far too bright to capture nebulae at the same time. During an eclipse, the moon darkens significantly and stars/nebulae will become visible. The main reason I’m proud of it was because it was a “make your own luck” kind of moment. Most of the western USA was set to have terrible weather for the eclipse, including where I live in Salt Lake City, Utah. After many hours of research, I decided my best shot was a 13-hour drive away in Roswell, New Mexico, where clouds were set to roll in shortly after the eclipse ended. My research paid off and I was one of the few to get excellent conditions. The alignment for this shot was lucky, but making it happen was hard work, and I’m proud of that!

I was drawn to the night sky over other forms of photography because it gives you the chance to see things that are otherwise invisible to your eyes. There’s a greater sense of exploration, and a chance to photograph subjects that are very interesting and rarely seen. From your own backyard you can watch the sun set over craters on the Moon, storms change on the surface of Jupiter and stars being born thousands of light years away. People say we were born too early to explore the cosmos, but it’s already possible.

From your own backyard you can watch the sun set over craters on the Moon, storms change on the surface of Jupiter, and stars being born thousands of light years away."

Astrophotography has really taught me to be patient when faced with challenges. The best part about shooting the stars is that they aren’t going anywhere. In astrophotography, you’re bound to have many miserable failures and wasted hours in the pursuit of a good image, but you can take any failure in your stride because there will always be another night to see the stars. The other important thing I’ve learned is that any overwhelming challenge you might face is usually just a bundle of simple challenges that can be handled in small bites. There is nothing you can’t accomplish in time with small consistent efforts.

Any overwhelming challenge you might face is usually just a bundle of simple challenges that can be handled in small bites."

Everyone does! My first was a small 4.5-inch Orion StarBlast Newtonian reflector. I chose it because it was the largest I could afford at the time. I definitely pushed it to its limits, and quickly moved to shooting with camera lenses. If anyone wants to know what telescope to get as their first, any Newtonian reflector – such as an 8-inch Dobsonian scope – will offer the best bang for your buck.

Apart from the immense cost of telescope equipment, the biggest challenge has to be light pollution. Artificial light from our cities obscures almost all the details of space from both our eyes and our telescopes. When imaging from a city, I have to use special narrowband filters to block out the brightness of the lights. If I want to even consider taking pictures of something in natural light, I drive out of the city and camp. Luckily, I grew up – and also now live – only 30 minutes away from dark skies. But for millions of people, especially in Europe, it can be very difficult to get to truly dark skies. Many people will go most of their lives without seeing the Milky Way, let alone photographing it. There is nothing like seeing the night sky as it’s meant to be seen, and I think everyone should get the chance at least once in their lives.

The biggest effect of has been the intense wildfires, which have got worse every summer here in the western USA. Smoke from California will travel hundreds of miles, from the Sierra Mountains into the whole desert south-west, blocking out the stars for weeks. Things only seem to get worse every year, and I often find myself checking satellite imagery to see where I can go to get out of the huge smoke clouds.

I think it has to be the behind-the-scenes video of bringing plants to life on camera. I love seeing how cameras can allow us to see invisible things, like the slow growth of plants through timelapsing. It’s also something I’ve always wanted to try!

As part of our Extremes series, we speak to fascinating nature photographers worldwide who withstand challenging conditions to tell stories about our amazing natural world and the wildlife species within it. Read all about Arctic expeditioner John Bozinov’s experiences shooting content in icy climes here.

Be the first to hear more inspiring stories by signing up to the BBC Earth newsletter below.

This interview was conducted via email.