BBC Earth Podcast

Close your eyes and open your ears

Intimate stories and surprising truths about nature, science and the human experience in a podcast the size of the planet.

People

Surely we’ve found everything there is to find? Not necessarily.

It’s easy to believe that we have mapped the entire world and that the idea of uncharted waters, mysterious islands untouched and creatures unseen by humankind seems fanciful. Surely satellite mapping means that we’ve found everything there is to find?

Not necessarily.

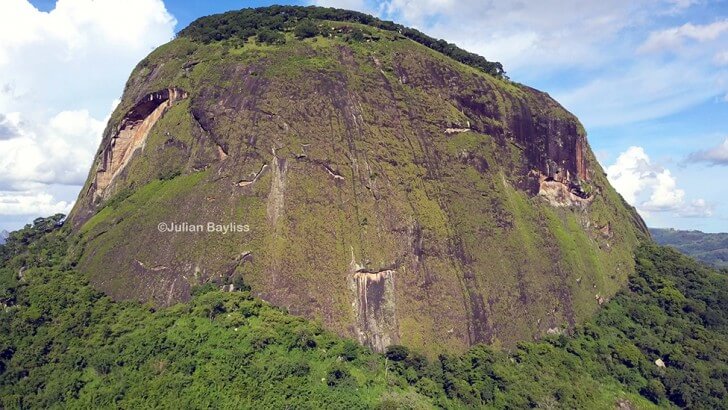

Meet your new explorer hero, Dr Julian Bayliss, an ecologist and conservation scientist, who tells us his story in the fifth episode of the BBC Earth Podcast. Dr Bayliss is in the unusual position of having discovered a new ecosystem. He saw it back in 2012 on satellite imagery, an undisturbed rainforest within a cratered mountain. This was Mount Lico, in northern Mozambique.

Dr Bayliss, the scientific advisor on the upcoming BBC Earth series Earth from Space, scours the world for undisturbed environments, like Mount Mabu, his rainforest discovery in Southern Africa. Using satellites, drones, camera tracking and remote sensing he discovers, then maps, inaccessible or simply unmapped areas.

He had spotted Mount Lico as a volcano-like mound, rising sharply up (the walls of the crater are 700m high in parts, and sheer), with a patch of dark green forest within a basin-shaped interior.

Five years later, having assembled a team of scientists, naturalists and researchers, Dr Bayliss flew to Mozambique. Talking to local communities around the base of Mount Lico, he was told as far as they knew no-one had ever been up the mountain. Again, using satellite imagery, he assessed which road, first tarmac and then dirt tracks, would take the team nearest to the mountain. He drove to within 6km of the base, then hiked with a drone to see the mountain which up until then had only been a bird’s-eye view image on a satellite.

The 700m crater walls meant that if Dr Bayliss wanted to get a close up view of what was in the crater, he’d need to use a drone, which went over the crater edge and promptly lost its line of sight. As the emergency lights flashed on the controller, Dr Bayliss despaired, thinking this was the last he’d the drone and his chances of getting any images of the forest within the crater. Thankfully the drone followed its path back and returned. He flew it again feeding the pictures back to his mobile phone, giving him his first glimpse of vines, creepers and birds flying – the first view of a lost world. Hugely excited, the team planned their ascent.

An immense and very hard climb followed. The team found a forest abundant with animal tracks, butterflies and birds. Scientists believe that in reality less than a quarter of the planet’s species have been classified and many new discoveries were made by Dr Bayliss’ explorers; a new species of butterfly (which Dr Bayliss intends naming after Mount Lico), an unknown species of amphibian, a fresh water crab and various never before seen small mammals and reptiles.

Mysteriously the group also found some upturned pots at the source of a stream, suggesting they were probably a spiritual offering from a medicine man to keep the water flowing down to the settlements below. No-one could imagine how the medicine man had ever reached that point as Dr Bayliss’ team had used specialist climbing equipment to climb the sheer crater walls.

Dr Bayliss describes a sense of awe and reverence at his discovery of Mount Lico, but it's not that uncommon once we stop believing that everything is known to us. Equally we can be convinced that places are there that actually aren’t. A group of Australian scientists recently attempted to visit Sandy Island, a speck of land in the Coral Sea near New Caledonia, only to discover that it didn’t exist. It was included on Australian maps by mistake and then appeared on Google Earth over a decade ago - except there’s nothing actually there.

A map or a satellite picture can only show us what’s there, not how to navigate it or the qualities it possesses. When we're using satellite maps to navigate a new city, we can feel a sense of sadness that we’re never going to discover that view, that area, by accident through our lost meanderings as it feels so mechanical. But turn the same satellite system on in a dense forest and you’re on your own. Technology can show us what’s there, but we should never believe that the world holds no more surprises.

Featured image © Dr Julian Bayliss

Intimate stories and surprising truths about nature, science and the human experience in a podcast the size of the planet.