BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

Blue Planet II

When the whale’s body gently breaches the surface of the water, Susan Parks must be at the ready.

Standing at the bow of a small boat, she has to lean in with a long pole, ready to stick a special gadget onto the whale’s back.

It’s a listening device that stays put for a day or less thanks to a suction cup.

When the device detaches, it floats to the surface and can be collected.

“They don’t really stay on very long because the idea of the tag is to not disturb the behaviour of the animal,” explains Parks, a biologist at Syracuse University in New York State.

“If they want to shed them they’ll come off – we’re limited to a sort of [brief] window into their lives.”

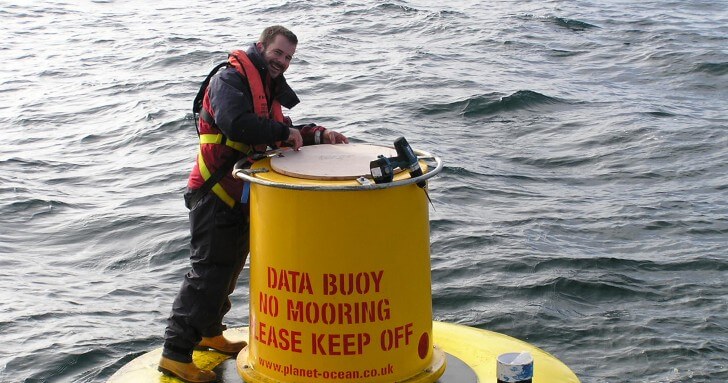

The suction cup method is great for tracking individual whales, but listening to the voices of many of these mammals in one area over a longer period of time is possible, too. Parks and researchers like her also commonly leave hydrophones hooked up to small hard drives underwater for months on end.

“We have just been completely blown away,” she says. “Our assumptions of where the whales are at different times have been upended by listening in an area year-round and discovering they’re there much more often than we thought, for longer periods.”

As the availability of such technology rises and the costs come down, Parks and others have been able to launch listening projects that were barely possible before.

John Hildebrand, for instance, at Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, has used large arrays of hydrophones to listen to whales with particularly deep calls. Blue whales and fin whales – the largest in the ocean – make noises at very low frequencies which means the sound can travel for many kilometres. This helps the animals, which are sometimes quite solitary, to stay in touch with one another.

But he and his team also study smaller whales that produce higher-pitched sounds, such as Cuvier’s whales that use echolocation clicks to target their prey. These whales change the rate of their clicks as they home in on the fish, squid or crustacean they’re hoping to eat.

When the whale realises there's an echo, it zooms in on that prey item by making the clicks go more rapidly"

“When [the whale] realises there's an echo, it zooms in on that prey item by making the clicks go more rapidly, because that's giving it more of an update of where the prey is,” explains Hildebrand, impersonating the whale over the phone by tapping quickly on his desk.

Thanks to acoustic monitoring, Hildebrand and his colleagues have recently found Cuvier’s whales in a part of the western North Atlantic Ocean, as reported in the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, where they had not previously been commonly detected, which has revealed how their habitat overlaps in places with another species.

In many parts of the world, just knowing what species are present in an area and how often remains a huge challenge. Off the coast of Great Britain and Ireland, for example, BBC News online reported about a new project called Compass is being set up to listen out for dolphin, porpoise and whale calls. There may be humpback, orca, minke and sperm whale observations, for example. But nobody knows just how often these species frequent the region.

“What we know is there isn’t enough baseline data to really understand what’s coming in and how often it’s here,” explains Adam Mellor at the Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute in Belfast.

It’s important to remember that we really do know very little about what animals get up to out there in the ocean – that vast place into which humans seldom venture. But gradually, thanks to a recent boom in this bioacoustics work, we are learning more about whales and dolphins – and the ways in which they use sound.

We’ve understood for a while, for instance, that these mammals will change their vocalisations to be better heard if man-made noise disturbs the area. They might get louder or shift the frequency they’re calling at for example.

“We’ve played back the sound of killer whales, which is a natural predator [to some species],” says Patrick Miller at the University of St Andrews.

By tracking prey species during such an experiment, researchers can observe the behavioural responses that are made. Stopping feeding is a classic one.

But reactions are also detectable when man-made noises penetrate their world.

“We also see how they respond to human sounds like sonar – they respond in similar ways.”

The harm caused to various marine species by different kinds of man-made noise remains the subject of much research, though we already know that in some cases whales have actually been found with physiological damage to their ears, according to one researcher at the Laboratory of Applied Bioacoustics at the Technical University of Catalonia, Barcelona, as reported by BBC Future online.

Whale song is one of nature’s most captivating and mysterious sounds. But just as we begin to tease apart its form and function in different species, noise pollution in the ocean, as reported by NRDC is reaching unprecedented levels.

It’s all the sadder when you realise how important vocalisation is for these mammals. Miller, for one, doesn’t believe that whales and dolphins have a language with information content comparable to humans, but he does note that these creatures probably have ways of interpreting each other’s calls more deeply than we humans – at least for now – can fathom.

He gives the example of killer whales, or orcas, which have been found to sing with different patterns in their songs depending on the social group to which they belong.

“More closely related groups […] have more similar sounds, in general,” he says. And it appears that over time calves may introduce subtle new patterns to the song – a sort of cultural heritage passed down within specific groups of whales.

It’s one of these things where the more you know about something, the more fascinating it is – you realise this is not simple, there’s a lot going on”

It’s not surprising that once people have interacted with whales, or listened to enough of their song-making, that they get hooked on the subject. That’s exactly what happened to John Hildebrand, who started his career listening to ocean sound recordings to see what could be learned about earthquakes.

“But these things were always filled with whale sounds and I just slowly, over the span of like a decade, realised they were really interesting,” he recalls. And the promise that one day we might better understand these majestic animals keeps him, and others like him, going.

“It’s one of these things where the more you know about something, the more fascinating it is – you realise this is not simple, there’s a lot going on.”

Featured image © Shevelle Stephens