BBC Earth newsletter

BBC Earth delivered direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive news, updates and exclusives from BBC Earth and related content from BBC Studios by email.

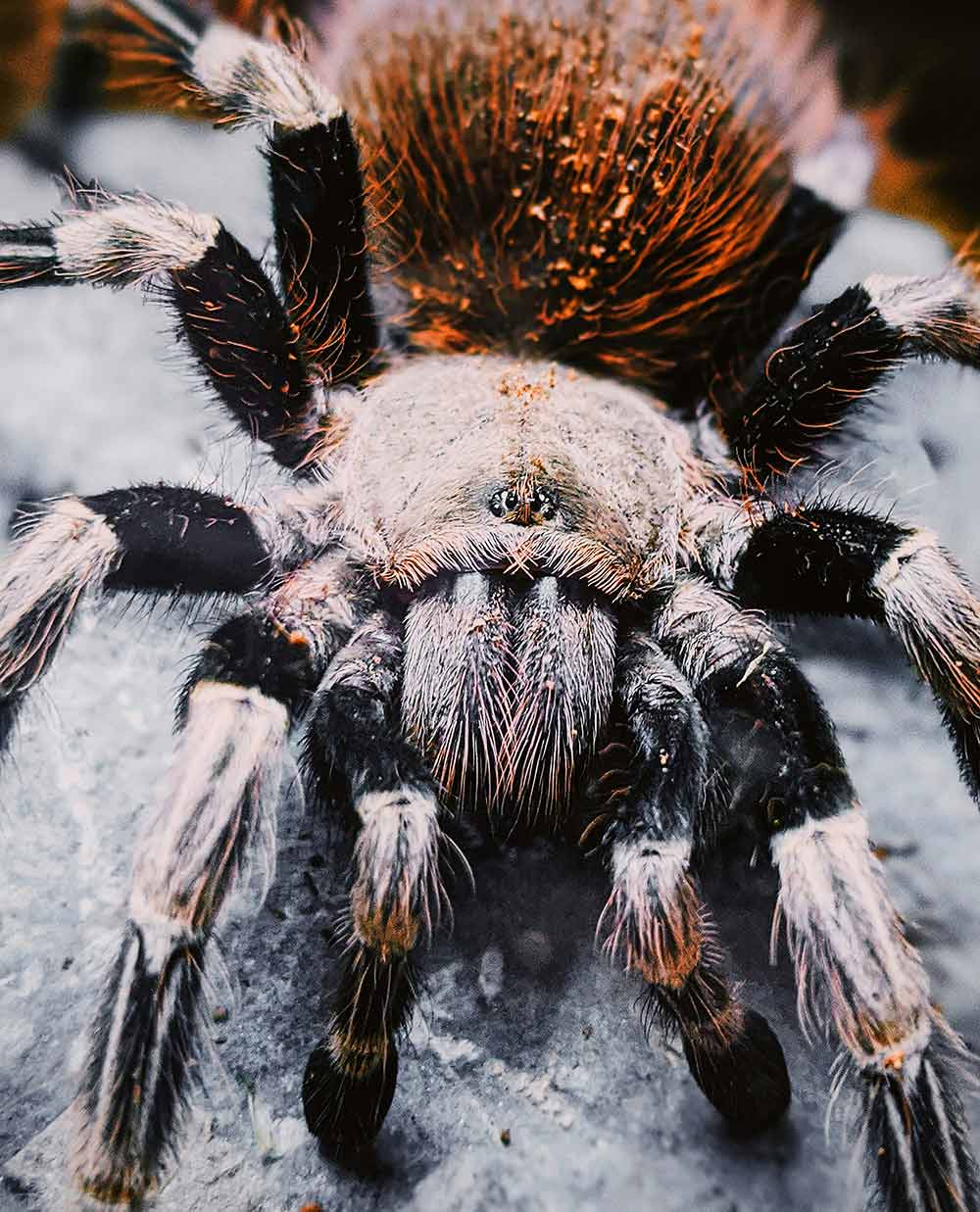

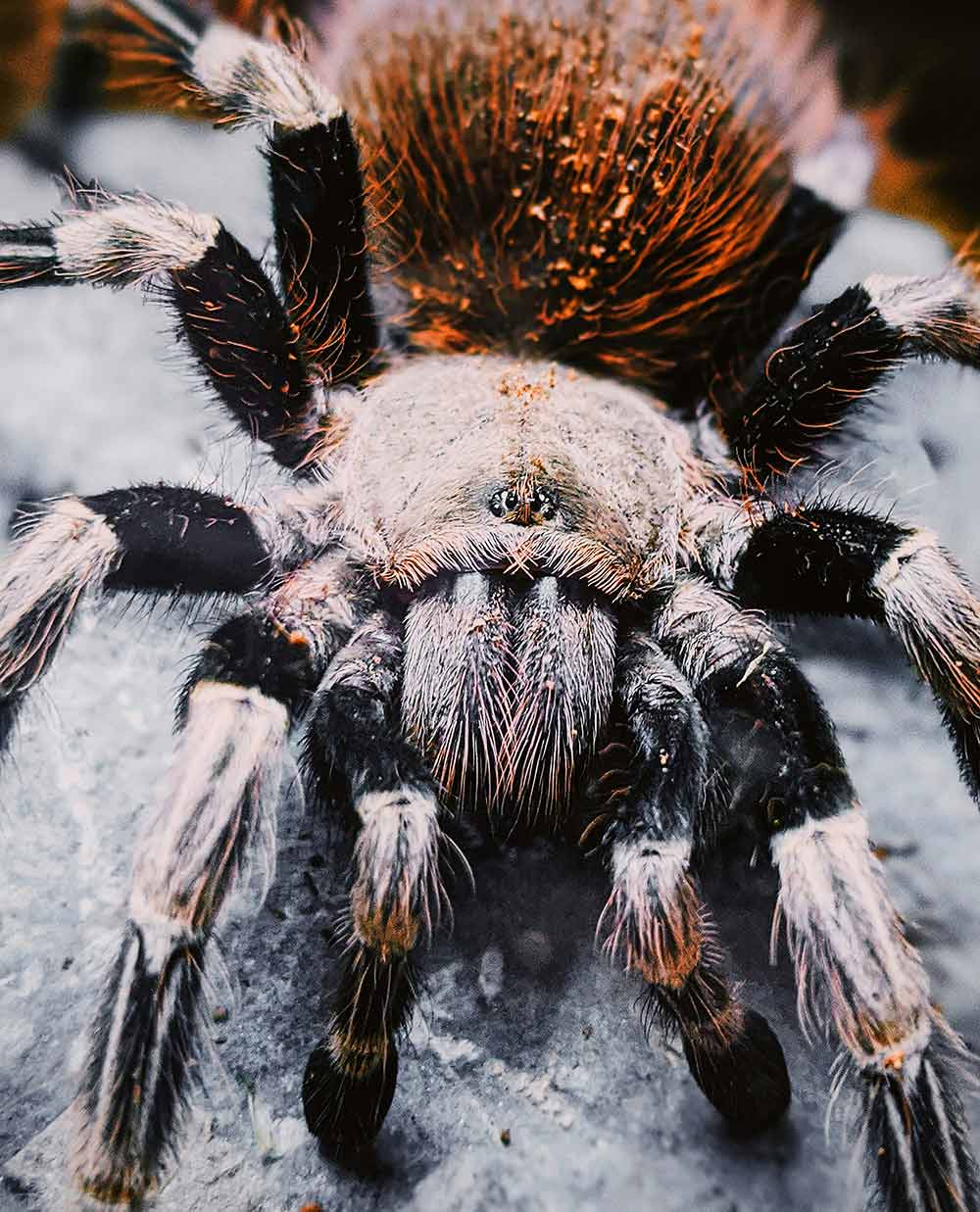

Known for their large, hairy appearance, tarantulas tend to evoke fear, yet they can also be docile and come in a surprising variety of shapes, colours and sizes.

Tarantulas are often feared for their large size, powerful bite and sharp fangs, as well as the spiky hairs they can shoot out like arrows. But there is a wide variety of tarantulas –ranging in size, colour, habitat, and behaviour – and we’re a threat to them much more than they are to us.

Yes, tarantulas are spiders. They are part of the group of animals called arachnids, and they are different from insects because they have four pairs of legs instead of three, no antennae and no wings, and their body is split into two segments instead of three.1

More specifically, tarantulas are all the spiders from the family Theraphosidae, which is then split up into over a thousand different species, each with their unique traits. The family Theraphosidae is part of the larger group of spiders called Mygalomorphs. Mygalomorphs are considered more primitive than their ‘true spider’ counterparts, which make up about 90% of spiders in the world.

Tarantulas haven’t always been the only spiders called tarantulas. At first, wolf spiders from the species Lycosa tarentula were given the name tarantula when they were found in the Italian town of Taranto.2 Their bite was thought to cause people to skip about erratically, mimicking what became a typical southern Italian dance: the tarantella. People started calling all large, hairy spiders they saw tarantulas, and the name stuck. They’re known as baboon spiders in Africa and hairy spiders in South America.3

Tarantulas are spiders from the family Theraphosidae. As of January 2025, there are 1,131 tarantula species across 169 different genera, according to the World Spider Catalogue, which is updated daily.

While tarantulas are iconic for being large, hairy spiders with powerful jaws, the high number of tarantula species also means there is a wide variation in what these spiders look like and how they behave.4 Some tarantulas are blue, green, purple, iridescent, or even speckled, like jewels.5 Some are as big as dinner plates and others are as tiny as match sticks.

“It’s really one of the largest spider families,” says Ivan Magalhaes, a spider evolution expert from the Natural History Museum of Argentina. “People always want to know about how dangerous tarantulas are, but I think that the most important aspect is first, how diverse they are, because we have very small species that are very colourful and live in trees and even species that live in deserts.”

Some tarantulas are blue, green, purple, iridescent, or even speckled, like jewels. Some are as big as dinner plates and others are as tiny as match sticks.

Tarantulas are among the largest spiders in the world. Their group also includes the Goliath bird-eaterfrom the rainforests of South America, which has a leg span of up to 30cm.6 That’s the size of a standard wooden ruler. The Brazilian salmon pink bird-eating tarantula is one of the largest tarantulas too, and it grows really fast, reaching its adult size in just two years.7

Not all tarantulas are large and long-legged, though – the Trinidad dwarf tarantula measures less than five centimetres, like the length of a matchstick, as does the Venezuelan red stripe tarantula.8

Tarantulas have four pairs of legs, just like all other arachnids. Each leg is split up into seven different little segments (ours are split into two!).9 The end of each leg has a couple of tiny retractable claws.

One fun thing about tarantula legs is that they don’t use their muscles to extend them. Instead, they pump fluid into their jointed legs and, like a hose filling up with water, the pressure helps them stretch their legs out.10

Sometimes it might look like tarantulas have an extra pair of legs, but those are their pedipalps.11 Pedipalps are the feelers at the front of their bodies that they use to probe and touch their surroundings, grip their prey, and understand more about the world around them – they are not used for moving like legs.

Tarantulas are found the world over, in every continent except Antarctica.12 They are mostly found in the Americas, especially in tropical and semi-tropical regions of South America. They also inhabit Asia , Africa, Australia, and the Mediterranean.13

Tarantulas have evolved to live in all sorts of different environments, from jungles to deserts to mountains to grasslands – and several species can live in cities too, thriving in manmade corners of city habitats like backyards, sports fields, and more.14

As to where they like to build their nests, most tarantula species live in silk-lined burrows and holes underground, beneath logs and stones. Some like to live up in the forest canopy, hanging out among tree tops, like the pink-toed tarantula or the Indian ornamental tarantula.15

Tarantulas are formidable hunters. While they spend most of the day hiding away in their burrows underground, or their crevices in trees, when dusk rolls around they are ready to go on the hunt for a snack.16

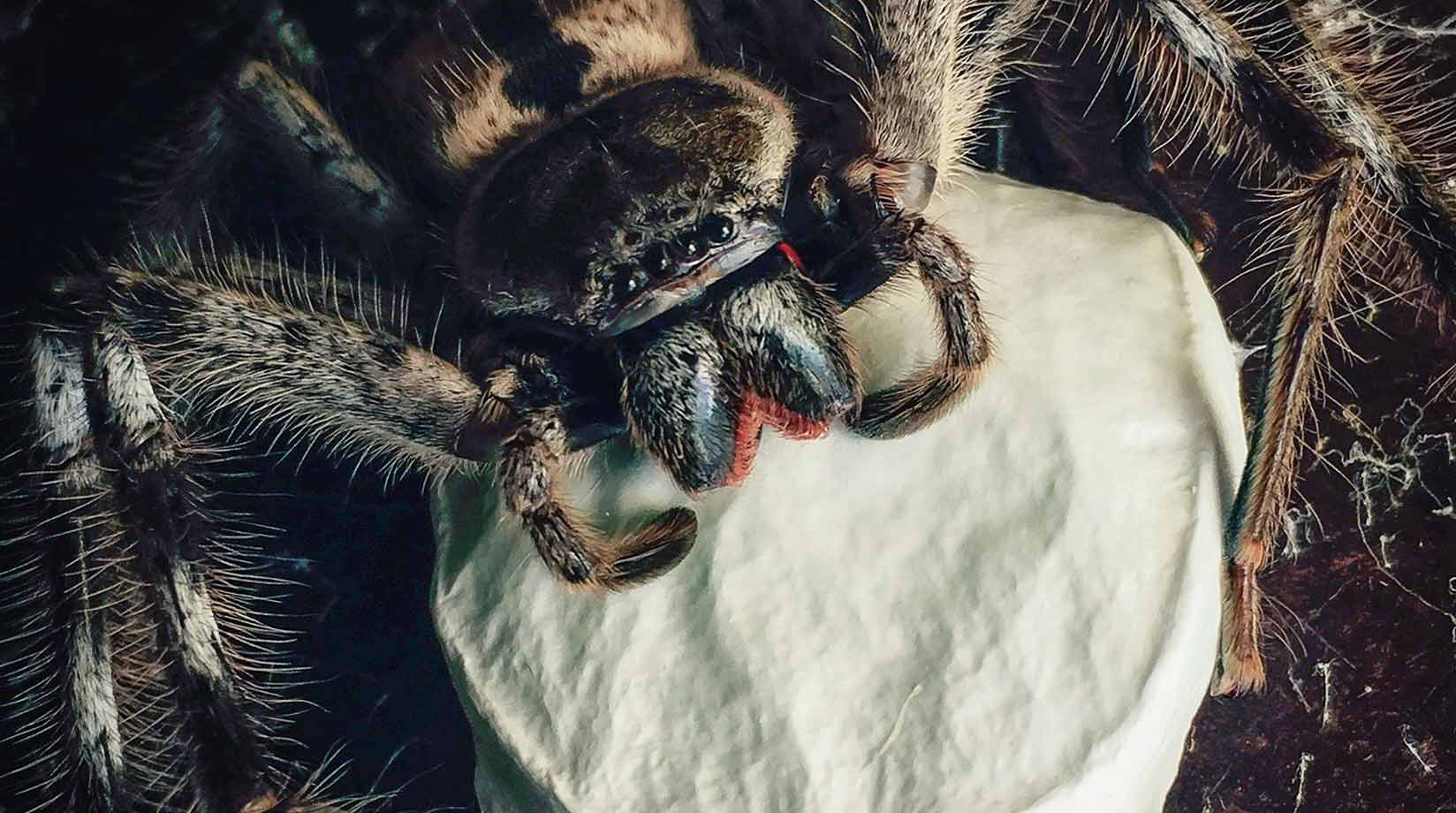

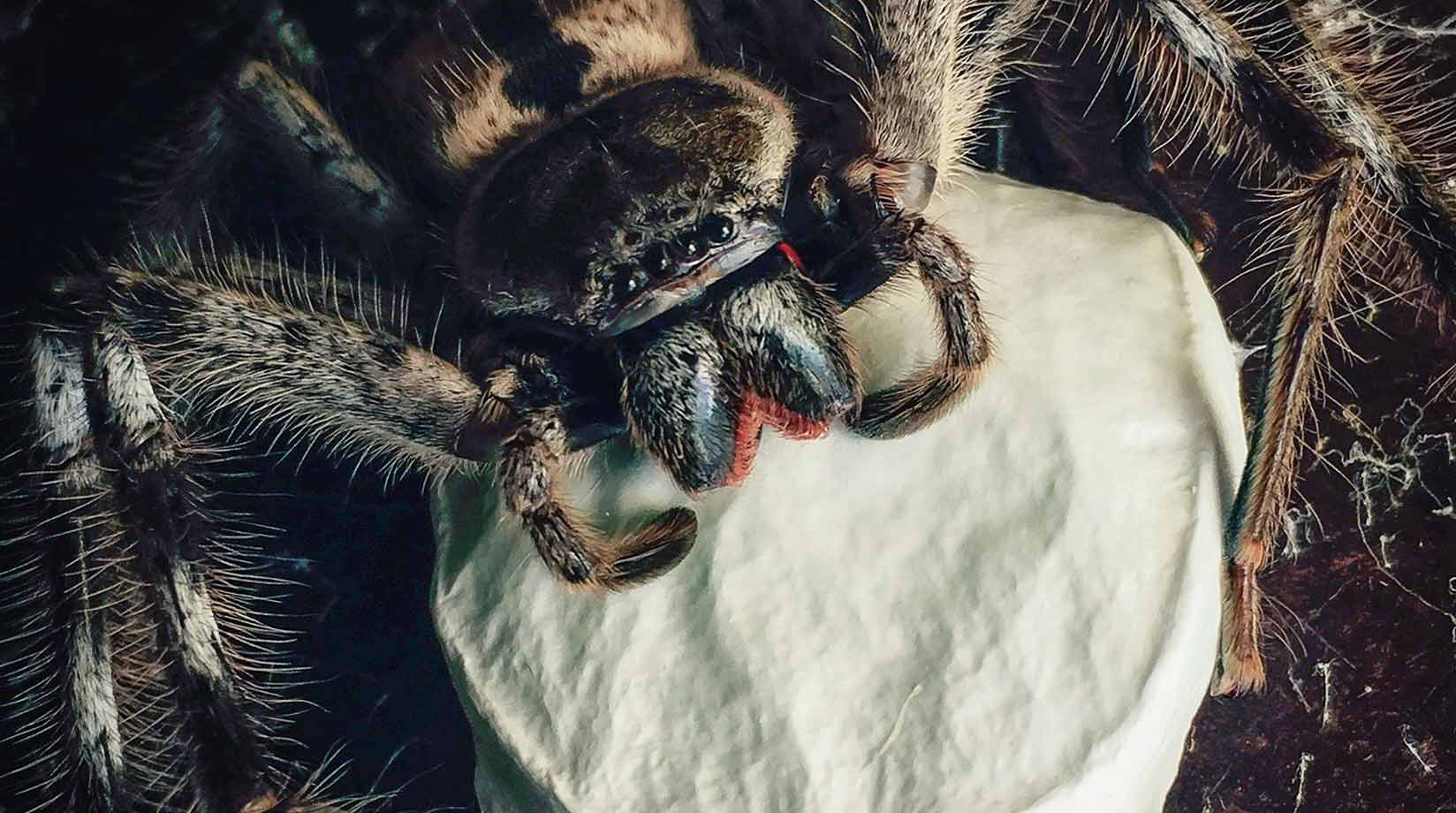

Unlike web-spinning spiders, tarantulas don’t use silk to catch their prey. Their webs are just used to protect their burrows and not to catch and lure prey. Instead, they prowl around – in some species, not farther than 40cm from their home – and then sit around and wait to pounce.17 Once they’ve found their prey, they stab them with their powerful fangs and inject them with venom, to immobilise them, liquefy them, and slurp them up.

Tarantulas are carnivorous: they like to snack on a wide range of insects, crickets, cockroaches, other smaller spiders, small reptiles like lizards and snakes, amphibians like frogs, and sometimes even small rodents and birds.

Tarantulas can bite, and their bite is painful, as some species have fangs as big as cheetah claws.18 But they’re not likely to inject venom in their predators – which is how they perceive humans – because their venom is costly for them to produce, and therefore a precious resource that shouldn’t be wasted.

And even if they were to inject their venom while biting a human, their venom isn’t lethal to us, says Alejandro García-Arredondo, who studies tarantula venom at Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, in Mexico. There are no records of human deaths caused by tarantula bites.19

However, according to Garcia-Arredondo, some species are underestimated though. For example, some tree-dwelling tarantulas native to Sri Lanka and India possess venom which can cause severe pain, burning sensations, fevers, flu-like symptoms, and muscle cramps for approximately one week.20

Tarantula venoms are special because they contain a complex mixture of compounds mainly made of peptides that affect the nervous system, says García-Arredondo. Interestingly, some components of the tarantula venom is similar to those found in other small spiders, black widows, or even in scorpions.

But it’s not all bad – scientists also study tarantula venoms for medical applications like a new type of non-addictive painkillers.21

Tarantulas are known for being very hairy, and they have shaggy hairs all over their abdomen and legs. Some species of New World tarantulas – those from North and South America – are also covered in over a million thick special hairs on their abdomens called urticating setae.22

By stroking their abdomen with their legs, tarantulas can fling the tiny hairs off their body and onto their predators. This is a defence mechanism. The setae have spines and barbs that can penetrate the skin and cause an itching, allergic reaction-like sensation. Some species have hairs so itchy they can cause itching rashes for up to three weeks. There are various different types of these urticating hairs, and different ones have different itching characteristics.23

“The hairs are a way to fend off the predators without having to use the venom or bite,” says Ivan Magalhaes, a spider evolution expert from the Natural History Museum of Argentina. Since their venom is very precious and costly to produce, it's better spent on prey. Some species even use their hairs when they wrap up their eggs in protective silk, so that the egg sacs have spiny defences too.24

Spiders don’t have a skeleton with bones on their inside like humans do – spiders are invertebrates – but they do have a hard outer shell that keeps them protected and is called an exoskeleton.

As tarantulas grow, their exoskeleton becomes too small for them. They have to crawl out of their outer skeleton in a process called moulting. Studies show that tarantulas tend to moult once or twice a year and pick up the moulting pace during their third year of life, moulting up to 10 times before they reach their adult size.25

Female tarantulas actually continue moulting even throughout adulthood. Even once they’ve reached sexual maturity. That’s why tarantulas are so long-lived, with females getting to be as old as 30, says arachnologist Laura Montes de Oca from the Republic University of Uruguay.

Unlike a lot of spiders we’re used to thinking about, tarantulas don’t use their silk to make beautiful, geometrical spider webs or messy, jumbled cobwebs at the corners of ceilings.

But, like all spiders, they make silk. They produce silk through organs of their body called spinnerets, from which they can spin threads of strong, resistant thread.26 Their silk is mainly used to line their burrow and make sure it maintains its shape.27 During the winter, silk is also used to plug the burrow shut and fend off the cold.28

In the early 2010s, scientists speculated the tarantulas could also spin silk from the tips of their legs, but further research cast doubt on these theories.29

Tarantulas have four pairs of eyes clustered on their heads, but they don’t see very well. “Our knowledge of tarantula vision is currently very limited. We know that they have relatively small eyes that provide a wide field of view at modest resolution,” says Nathan Morehouse, an expert on spider vision from the University of Cincinnati.

Some research does suggest that tarantula species that live on trees have evolved larger eyes, though, and likely see better than their burrowing counterparts.30

Since they go out at night, when colours are muted, tarantulas have long been thought to be colourblind. Yet, some species exhibit vibrant, colourful spots and strides on their legs – suggesting maybe there’s more to tarantula vision than meets the eye. In fact, scientists in 2020 discovered that tarantulas actually have a wide variety of genes that regulate colour vision.31 But research connecting these genes to actual vision capabilities is still ongoing, says Morehouse. For sensing their surroundings, tarantulas rely heavily on all the little hairs covering their bodies.

Depending on the sex and species, it takes anywhere from five to 10 years to reach sexual maturity for tarantulas, and males tend to mature before females. “This makes sense if we think that from the same egg sac, brothers will avoid mating with their sisters,” says arachnologist Laura Montes de Oca from the Republic University of Uruguay.

Males have structures called bulbs at the end of their pedipalps. They charge the bulbs with droplets of their sperm and they’ll use the bulbs for mating, says Montes de Oca. Then they start their “wandering life” looking for the perfect female to mate with – with some species walking more than 300 metres per day – and they follow scent chemicals the females release and cover their burrows and webs with.32

When they reach their potential mate, they start to court the female. If a male's deemed worthy, the female will exit her hiding spot and allow him to mate with her, says Montes de Oca. But Montes de Oca’s studies also suggest success in mating depends on whether the temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pressure is perfect – tarantulas are picky!33

And this mating ritual doesn’t always end well, though. Since males are mostly smaller than females, if females aren’t in the mood for mating or they don’t feel their suitor is up to the job, they stop seeing it as a possible mate and start seeing it as a possible meal. “If you're not a partner, you’re food,” says Ivan Magalhaes, a spider evolution expert from the Natural History Museum of Argentina. For tarantulas, there is an added pressure: the mating position is very tricky, and it involves the small male going straight under the female’s fangs.

“It's very dangerous, because if she changes her mind at any time, she just can grab him,” says Magalhaes. To protect themselves, many male tarantulas have hooks on their front pair of legs to lift the female off and buy time if she becomes aggressive. There is a lot of variation in these hooks – some species have three branches in the hook, other species have just two – and it's actually one of the features that scientists use to tell tarantula species apart, says Magalhaes.

After mating, a female tarantula can store sperm and fertilise her eggs months later . Over the course of her life, she’ll lay hundreds of eggs, wrap them up in a silk cocoon, and then wait for them to hatch for up to nine weeks, depending on the species.

“During this time, the mother will move and roll the cocoon within her shelter to maintain optimal temperature and humidity conditions,” says arachnologist Fernando Pérez-Miles from the Republic University of Uruguay. Tarantula egg sacs usually contain between 100 and 300 eggs.34

After hatching, the spiderlings remain in the silk cocoon for a few moults of their exoskeleton before they’re ready to pop out. The spiderlings stay close to the mother within the shelter and feed on food scraps left by her and do so until they are ready to flee the nest a couple of months later, says Pérez-Miles.

Tarantulas don't keep frogs ‘as pets’, but almost 100 species of tarantulas are known to have mutualistic relationships with frogs: they help the frogs, and the frogs help them.35 Frogs living inside tarantula burrows gain shelter and protection from predators, such as snakes. In return, the tarantula benefits from the frogs feeding on injurious insects, such as ants and parasitoid flies, which could otherwise harm the tarantula, its eggs, or its juveniles.

“This relationship is quite unique, as no other groups of spiders are known to associate with any species of vertebrates,” says Alireza Zamani, an arachnologist at the University of Turku in Finland, who co-authored a study looking at all of the cases of tarantulas pairing up with frogs.36

Tarantulas seem to be quite picky in their friendships: they tolerate only certain frog species in their burrows and will attack others, even if they’re the same size. Narrowmouth toads are those most commonly found living with tarantulas.They’re so good at living with tarantulas that they can tell the difference between spiderlings and termites and only feed on the termites, says Zamani.

“These relationships not only challenge the common belief that tarantulas are ‘mindless killers,’ they also demonstrate how little we know about the biodiversity of our planet,” says Zamani.

Yes, tarantulas – especially arboreal species that live up in trees – can jump, according to Ivan Magalhaes, a spider evolution expert from the Natural History Museum of Argentina. However, this behaviour remains contested, as it has not been officially recorded.

Tarantulas can also climb up on vertical and inverted surfaces thanks to the sticky hair pads they have under their feet.37

What they cannot do is hang themselves from their silk as many other spider species do. Tarantulas are so ancient that spiders hadn’t yet evolved the capability to hang from their silk when their species was born.

Tarantulas cannot growl: they don’t have vocal chords.

They can, however, make high-pitched sounds by rubbing together some of their scraping hairs called stridulating setae.38 “Sometimes, this vibration is audible as a hissing sound,” says arachnologist José Paulo Leite Guadanucci from the Universidade Estadual Paulista in Brazil.

These setae are located in between legs or on their pedipalps, on opposite sides, so they can rub, “like a velcro strip,” says Guadanucci. “Here in South America, we have the Goliath spider that even sounds like a rattlesnake, but not as loud.” Overall, spiders make a lot of vibration movements, clearly seen in their legs and body, that aren’t audible as sounds to us, but they might be audible among themselves.

Many tarantula species are endangered. Some species are at risk of extinction because the expansion of cities and agricultural growth is destroying much of their habitat. Plus, humans illegally and legally capture and trade tarantulas for the exotic pet market.39

Research from 2022 calculated that as much as 50% of the illegal spider trade is for tarantulas, and that in South Africa alone more than 130 species of tarantulas are traded.40

Tarantulas are particularly vulnerable because of their slow growth. They are very large, so they take a long time to reach maturity. They risk dying before they’ve had time to reproduce, says Ivan Magalhaes, a spider evolution expert from the Natural History Museum of Argentina. “People are scared of them, but actually humans as a collective species, are much more dangerous to all the tarantulas than any of the tarantulas are dangerous to humans.”

Featured image © Hong Bin | Unsplash

Fun fact image © Julian Schultz | Unsplash

Quick Facts:

Interviews:

The interview with Ivan Magalhaes, a spider evolution expert from the Natural History Museum of Argentina, was conducted over Zoom in November 2024. More about Dr. Magalhaes: https://ilfmagalhaes.wixsite.com/home

Interviews with arachnologists Laura Montes de Oca and Fernando Pérez-Miles from the Republic University of Uruguay, Nathan Morehouse from the University of Cincinnati, Alireza Zamani from the University of Turku in Finland, and José Paulo Leite Guadanucci from the Universidade Estadual Paulista in Brazil were conducted over email in November 2024.

More about these scholars:

Fact File:

Known for their large, hairy appearance, tarantulas tend to evoke fear, yet they can also be docile and come in a surprising variety of shapes, colours and sizes.

Spiderlings

Cluster, clutter

Mainly insects, other small arachnids, tiny vertebrates like reptiles, small mammals and sometimes birds

Birds, Reptiles, Mammals

While males live about 10 years, females can live until they’re 30

On average, tarantulas are between 10cm and 13cm in leg span. The Goliath bird-eater can have a leg span of up to 30cm and is the largest spider on Earth3

On average they weigh about 30g, but Goliath bird-eater tarantulas can weigh more than 100g.4

From jungles to deserts to mountains to grasslands – and several species can live in cities too

n/a

Least Concern as a group — but some species are endangered

Female tarantulas don’t always eat their male partners after mating, but they often snack on them instead!

Tarantulas are often feared for their large size, powerful bite and sharp fangs, as well as the spiky hairs they can shoot out like arrows. But there is a wide variety of tarantulas –ranging in size, colour, habitat, and behaviour – and we’re a threat to them much more than they are to us.

Yes, tarantulas are spiders. They are part of the group of animals called arachnids, and they are different from insects because they have four pairs of legs instead of three, no antennae and no wings, and their body is split into two segments instead of three.1

More specifically, tarantulas are all the spiders from the family Theraphosidae, which is then split up into over a thousand different species, each with their unique traits. The family Theraphosidae is part of the larger group of spiders called Mygalomorphs. Mygalomorphs are considered more primitive than their ‘true spider’ counterparts, which make up about 90% of spiders in the world.

Tarantulas haven’t always been the only spiders called tarantulas. At first, wolf spiders from the species Lycosa tarentula were given the name tarantula when they were found in the Italian town of Taranto.2 Their bite was thought to cause people to skip about erratically, mimicking what became a typical southern Italian dance: the tarantella. People started calling all large, hairy spiders they saw tarantulas, and the name stuck. They’re known as baboon spiders in Africa and hairy spiders in South America.3

Tarantulas are spiders from the family Theraphosidae. As of January 2025, there are 1,131 tarantula species across 169 different genera, according to the World Spider Catalogue, which is updated daily.

While tarantulas are iconic for being large, hairy spiders with powerful jaws, the high number of tarantula species also means there is a wide variation in what these spiders look like and how they behave.4 Some tarantulas are blue, green, purple, iridescent, or even speckled, like jewels.5 Some are as big as dinner plates and others are as tiny as match sticks.

“It’s really one of the largest spider families,” says Ivan Magalhaes, a spider evolution expert from the Natural History Museum of Argentina. “People always want to know about how dangerous tarantulas are, but I think that the most important aspect is first, how diverse they are, because we have very small species that are very colourful and live in trees and even species that live in deserts.”

Some tarantulas are blue, green, purple, iridescent, or even speckled, like jewels. Some are as big as dinner plates and others are as tiny as match sticks.

Tarantulas are among the largest spiders in the world. Their group also includes the Goliath bird-eaterfrom the rainforests of South America, which has a leg span of up to 30cm.6 That’s the size of a standard wooden ruler. The Brazilian salmon pink bird-eating tarantula is one of the largest tarantulas too, and it grows really fast, reaching its adult size in just two years.7

Not all tarantulas are large and long-legged, though – the Trinidad dwarf tarantula measures less than five centimetres, like the length of a matchstick, as does the Venezuelan red stripe tarantula.8

Tarantulas have four pairs of legs, just like all other arachnids. Each leg is split up into seven different little segments (ours are split into two!).9 The end of each leg has a couple of tiny retractable claws.

One fun thing about tarantula legs is that they don’t use their muscles to extend them. Instead, they pump fluid into their jointed legs and, like a hose filling up with water, the pressure helps them stretch their legs out.10

Sometimes it might look like tarantulas have an extra pair of legs, but those are their pedipalps.11 Pedipalps are the feelers at the front of their bodies that they use to probe and touch their surroundings, grip their prey, and understand more about the world around them – they are not used for moving like legs.

Tarantulas are found the world over, in every continent except Antarctica.12 They are mostly found in the Americas, especially in tropical and semi-tropical regions of South America. They also inhabit Asia , Africa, Australia, and the Mediterranean.13

Tarantulas have evolved to live in all sorts of different environments, from jungles to deserts to mountains to grasslands – and several species can live in cities too, thriving in manmade corners of city habitats like backyards, sports fields, and more.14

As to where they like to build their nests, most tarantula species live in silk-lined burrows and holes underground, beneath logs and stones. Some like to live up in the forest canopy, hanging out among tree tops, like the pink-toed tarantula or the Indian ornamental tarantula.15

Tarantulas are formidable hunters. While they spend most of the day hiding away in their burrows underground, or their crevices in trees, when dusk rolls around they are ready to go on the hunt for a snack.16

Unlike web-spinning spiders, tarantulas don’t use silk to catch their prey. Their webs are just used to protect their burrows and not to catch and lure prey. Instead, they prowl around – in some species, not farther than 40cm from their home – and then sit around and wait to pounce.17 Once they’ve found their prey, they stab them with their powerful fangs and inject them with venom, to immobilise them, liquefy them, and slurp them up.

Tarantulas are carnivorous: they like to snack on a wide range of insects, crickets, cockroaches, other smaller spiders, small reptiles like lizards and snakes, amphibians like frogs, and sometimes even small rodents and birds.

Tarantulas can bite, and their bite is painful, as some species have fangs as big as cheetah claws.18 But they’re not likely to inject venom in their predators – which is how they perceive humans – because their venom is costly for them to produce, and therefore a precious resource that shouldn’t be wasted.

And even if they were to inject their venom while biting a human, their venom isn’t lethal to us, says Alejandro García-Arredondo, who studies tarantula venom at Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, in Mexico. There are no records of human deaths caused by tarantula bites.19

However, according to Garcia-Arredondo, some species are underestimated though. For example, some tree-dwelling tarantulas native to Sri Lanka and India possess venom which can cause severe pain, burning sensations, fevers, flu-like symptoms, and muscle cramps for approximately one week.20

Tarantula venoms are special because they contain a complex mixture of compounds mainly made of peptides that affect the nervous system, says García-Arredondo. Interestingly, some components of the tarantula venom is similar to those found in other small spiders, black widows, or even in scorpions.

But it’s not all bad – scientists also study tarantula venoms for medical applications like a new type of non-addictive painkillers.21

Tarantulas are known for being very hairy, and they have shaggy hairs all over their abdomen and legs. Some species of New World tarantulas – those from North and South America – are also covered in over a million thick special hairs on their abdomens called urticating setae.22

By stroking their abdomen with their legs, tarantulas can fling the tiny hairs off their body and onto their predators. This is a defence mechanism. The setae have spines and barbs that can penetrate the skin and cause an itching, allergic reaction-like sensation. Some species have hairs so itchy they can cause itching rashes for up to three weeks. There are various different types of these urticating hairs, and different ones have different itching characteristics.23

“The hairs are a way to fend off the predators without having to use the venom or bite,” says Ivan Magalhaes, a spider evolution expert from the Natural History Museum of Argentina. Since their venom is very precious and costly to produce, it's better spent on prey. Some species even use their hairs when they wrap up their eggs in protective silk, so that the egg sacs have spiny defences too.24

Spiders don’t have a skeleton with bones on their inside like humans do – spiders are invertebrates – but they do have a hard outer shell that keeps them protected and is called an exoskeleton.

As tarantulas grow, their exoskeleton becomes too small for them. They have to crawl out of their outer skeleton in a process called moulting. Studies show that tarantulas tend to moult once or twice a year and pick up the moulting pace during their third year of life, moulting up to 10 times before they reach their adult size.25

Female tarantulas actually continue moulting even throughout adulthood. Even once they’ve reached sexual maturity. That’s why tarantulas are so long-lived, with females getting to be as old as 30, says arachnologist Laura Montes de Oca from the Republic University of Uruguay.

Unlike a lot of spiders we’re used to thinking about, tarantulas don’t use their silk to make beautiful, geometrical spider webs or messy, jumbled cobwebs at the corners of ceilings.

But, like all spiders, they make silk. They produce silk through organs of their body called spinnerets, from which they can spin threads of strong, resistant thread.26 Their silk is mainly used to line their burrow and make sure it maintains its shape.27 During the winter, silk is also used to plug the burrow shut and fend off the cold.28

In the early 2010s, scientists speculated the tarantulas could also spin silk from the tips of their legs, but further research cast doubt on these theories.29

Tarantulas have four pairs of eyes clustered on their heads, but they don’t see very well. “Our knowledge of tarantula vision is currently very limited. We know that they have relatively small eyes that provide a wide field of view at modest resolution,” says Nathan Morehouse, an expert on spider vision from the University of Cincinnati.

Some research does suggest that tarantula species that live on trees have evolved larger eyes, though, and likely see better than their burrowing counterparts.30

Since they go out at night, when colours are muted, tarantulas have long been thought to be colourblind. Yet, some species exhibit vibrant, colourful spots and strides on their legs – suggesting maybe there’s more to tarantula vision than meets the eye. In fact, scientists in 2020 discovered that tarantulas actually have a wide variety of genes that regulate colour vision.31 But research connecting these genes to actual vision capabilities is still ongoing, says Morehouse. For sensing their surroundings, tarantulas rely heavily on all the little hairs covering their bodies.

Depending on the sex and species, it takes anywhere from five to 10 years to reach sexual maturity for tarantulas, and males tend to mature before females. “This makes sense if we think that from the same egg sac, brothers will avoid mating with their sisters,” says arachnologist Laura Montes de Oca from the Republic University of Uruguay.

Males have structures called bulbs at the end of their pedipalps. They charge the bulbs with droplets of their sperm and they’ll use the bulbs for mating, says Montes de Oca. Then they start their “wandering life” looking for the perfect female to mate with – with some species walking more than 300 metres per day – and they follow scent chemicals the females release and cover their burrows and webs with.32

When they reach their potential mate, they start to court the female. If a male's deemed worthy, the female will exit her hiding spot and allow him to mate with her, says Montes de Oca. But Montes de Oca’s studies also suggest success in mating depends on whether the temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pressure is perfect – tarantulas are picky!33

And this mating ritual doesn’t always end well, though. Since males are mostly smaller than females, if females aren’t in the mood for mating or they don’t feel their suitor is up to the job, they stop seeing it as a possible mate and start seeing it as a possible meal. “If you're not a partner, you’re food,” says Ivan Magalhaes, a spider evolution expert from the Natural History Museum of Argentina. For tarantulas, there is an added pressure: the mating position is very tricky, and it involves the small male going straight under the female’s fangs.

“It's very dangerous, because if she changes her mind at any time, she just can grab him,” says Magalhaes. To protect themselves, many male tarantulas have hooks on their front pair of legs to lift the female off and buy time if she becomes aggressive. There is a lot of variation in these hooks – some species have three branches in the hook, other species have just two – and it's actually one of the features that scientists use to tell tarantula species apart, says Magalhaes.

After mating, a female tarantula can store sperm and fertilise her eggs months later . Over the course of her life, she’ll lay hundreds of eggs, wrap them up in a silk cocoon, and then wait for them to hatch for up to nine weeks, depending on the species.

“During this time, the mother will move and roll the cocoon within her shelter to maintain optimal temperature and humidity conditions,” says arachnologist Fernando Pérez-Miles from the Republic University of Uruguay. Tarantula egg sacs usually contain between 100 and 300 eggs.34

After hatching, the spiderlings remain in the silk cocoon for a few moults of their exoskeleton before they’re ready to pop out. The spiderlings stay close to the mother within the shelter and feed on food scraps left by her and do so until they are ready to flee the nest a couple of months later, says Pérez-Miles.

Tarantulas don't keep frogs ‘as pets’, but almost 100 species of tarantulas are known to have mutualistic relationships with frogs: they help the frogs, and the frogs help them.35 Frogs living inside tarantula burrows gain shelter and protection from predators, such as snakes. In return, the tarantula benefits from the frogs feeding on injurious insects, such as ants and parasitoid flies, which could otherwise harm the tarantula, its eggs, or its juveniles.

“This relationship is quite unique, as no other groups of spiders are known to associate with any species of vertebrates,” says Alireza Zamani, an arachnologist at the University of Turku in Finland, who co-authored a study looking at all of the cases of tarantulas pairing up with frogs.36

Tarantulas seem to be quite picky in their friendships: they tolerate only certain frog species in their burrows and will attack others, even if they’re the same size. Narrowmouth toads are those most commonly found living with tarantulas.They’re so good at living with tarantulas that they can tell the difference between spiderlings and termites and only feed on the termites, says Zamani.

“These relationships not only challenge the common belief that tarantulas are ‘mindless killers,’ they also demonstrate how little we know about the biodiversity of our planet,” says Zamani.

Yes, tarantulas – especially arboreal species that live up in trees – can jump, according to Ivan Magalhaes, a spider evolution expert from the Natural History Museum of Argentina. However, this behaviour remains contested, as it has not been officially recorded.

Tarantulas can also climb up on vertical and inverted surfaces thanks to the sticky hair pads they have under their feet.37

What they cannot do is hang themselves from their silk as many other spider species do. Tarantulas are so ancient that spiders hadn’t yet evolved the capability to hang from their silk when their species was born.

Tarantulas cannot growl: they don’t have vocal chords.

They can, however, make high-pitched sounds by rubbing together some of their scraping hairs called stridulating setae.38 “Sometimes, this vibration is audible as a hissing sound,” says arachnologist José Paulo Leite Guadanucci from the Universidade Estadual Paulista in Brazil.

These setae are located in between legs or on their pedipalps, on opposite sides, so they can rub, “like a velcro strip,” says Guadanucci. “Here in South America, we have the Goliath spider that even sounds like a rattlesnake, but not as loud.” Overall, spiders make a lot of vibration movements, clearly seen in their legs and body, that aren’t audible as sounds to us, but they might be audible among themselves.

Many tarantula species are endangered. Some species are at risk of extinction because the expansion of cities and agricultural growth is destroying much of their habitat. Plus, humans illegally and legally capture and trade tarantulas for the exotic pet market.39

Research from 2022 calculated that as much as 50% of the illegal spider trade is for tarantulas, and that in South Africa alone more than 130 species of tarantulas are traded.40

Tarantulas are particularly vulnerable because of their slow growth. They are very large, so they take a long time to reach maturity. They risk dying before they’ve had time to reproduce, says Ivan Magalhaes, a spider evolution expert from the Natural History Museum of Argentina. “People are scared of them, but actually humans as a collective species, are much more dangerous to all the tarantulas than any of the tarantulas are dangerous to humans.”

Featured image © Hong Bin | Unsplash

Fun fact image © Julian Schultz | Unsplash

Quick Facts:

Interviews:

The interview with Ivan Magalhaes, a spider evolution expert from the Natural History Museum of Argentina, was conducted over Zoom in November 2024. More about Dr. Magalhaes: https://ilfmagalhaes.wixsite.com/home

Interviews with arachnologists Laura Montes de Oca and Fernando Pérez-Miles from the Republic University of Uruguay, Nathan Morehouse from the University of Cincinnati, Alireza Zamani from the University of Turku in Finland, and José Paulo Leite Guadanucci from the Universidade Estadual Paulista in Brazil were conducted over email in November 2024.

More about these scholars:

Fact File:

Spiderlings

Cluster, clutter

Mainly insects, other small arachnids, tiny vertebrates like reptiles, small mammals and sometimes birds

Birds, Reptiles, Mammals

While males live about 10 years, females can live until they’re 30

On average, tarantulas are between 10cm and 13cm in leg span. The Goliath bird-eater can have a leg span of up to 30cm and is the largest spider on Earth3

On average they weigh about 30g, but Goliath bird-eater tarantulas can weigh more than 100g.4

From jungles to deserts to mountains to grasslands – and several species can live in cities too

n/a

Least Concern as a group — but some species are endangered

Female tarantulas don’t always eat their male partners after mating, but they often snack on them instead!